It's a squishy, sloppy time to be making baby food for a living.

The greatest threat to food manufacturers is frustratingly simple: More parents are preparing their own baby food, an option that is cheaper, gives gives them control over what they feed their children, and turns out to be very convenient if made in large batches to freeze and use later as needed.

It's also a trend that many people find annoying — one user on Twitter insisted that the blender crowd "check your 'able to think and chop and blend and wash a blender' privilege."

Yet despite such critiques, "Commercially prepared baby food has been declining in volume since 2005, due to the trend of making baby food at home," according to the market researcher Euromonitor International.

Companies are stumbling to make commercially blended cereals, fruits, and vegetables sexier to parents...somehow. Innovation in the baby food business these days involves incorporating adult tastes into recipes, creating new food textures, and offering natural varieties.

And all these nouveau nibbles are getting more expensive. Pricey squeezable pouches and cereal puffs have driven up the average unit price for prepared baby food by an average of 2% annually from 2011 to 2016, according to Euromonitor. The average price for baby food has jumped by 14% since 2014, show data from IRI, a Chicago-based market research firm.

Yet there's competition from all the specialized gadgetry on store shelves now to help parents to prep baby food at home. The choices range from the low-cost Infantino Fresh Squeezed Squeeze Station ($16.99 at Target) and NUK Smoothie & Baby Food Maker ($33.47 at Jet) to the pricier Baby Bullet system ($69.99 at Target) and the Baby Brezza one-step food maker, which comes with reusable pouches for the blended food ($129.99 at BabyBrezza.com). Smiley faces and other kid-friendly details make clear: These are not meant for mixing up margaritas.

If parents can make everyday baby foods themselves, the solution, manufacturers say, is to go upscale.

Like most manufactured foods, baby food didn't take off till the early 1900s, according to a book, Inventing Baby Food, by NYU professor Amy Bentley. After World War II, almost all babies were eating commercial baby food, and companies were using preservatives, sugar, salt, and MSG — ingredients that major manufacturers later removed when consumer demands changed.

As it was, baby food was a tough business by nature. The window to sell pureed fruits and vegetables to any new parent is but a few short months — typically peaking when an infant is 6 months to 9 months old — before they move on to more mature foods. Add to that the fact that the fertility rate in the US reached a record low in 2016.

Make my own baby food or buy it from the store?

"We saw a lot of the volume leaving the category," said Andy Dahlen, vice president of marketing at Beech-Nut, the second biggest baby food brand after Gerber. "The category was in trouble."

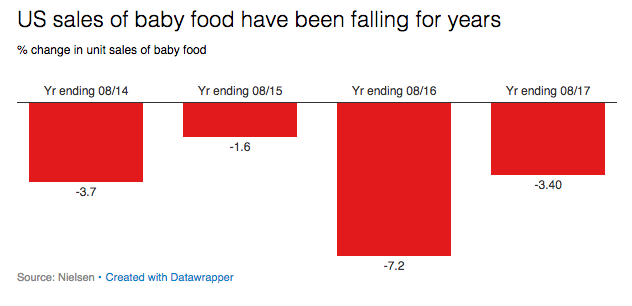

And while pouches have become ubiquitous since they were introduced about nine years ago, they haven't reversed the market's broader softness. In the 12 months ending in August, volume sales of baby food industry-wide were down 3.4%, according to Nielsen. Sales of baby formula were also down 3.7% because more women are breastfeeding.

"More than in nearly any other category, consumers want good, clean and healthy baby food," said Jordan Rost, vice president of consumer insights at Nielsen. "Food companies have been smart to grow the assortment of organic baby foods they offer, and consumers are responding."

The market share for organic baby food has jumped, particularly in products aimed at toddlers rather than infants: Organics now make up 20% of "first foods" sales and 40% of "stage 3" foods, Rost said, "indicating that the older our children get, the more focus we place on getting them better foods."

Gerber said it is not fighting homemade baby food — instead, the company said, it aims to be the chosen brand when parents can't or don't choose to make their own.

"We embrace those parents who get more involved in food making," said a Gerber spokesperson to BuzzFeed News. The company invested over $100 million in a new line of chunky baby food called Lil' Bits that launched in 2015. It integrated foods like kale and quinoa into its pouches "to expose baby to delicious tastes and help squeeze more veggies in the diet," the spokesperson said.

Beech-Nut, once known as the value brand, introduced natural and organic lines and added trendy toddler foods like quinoa bars, in an effort to keep parents buying long after their children move on from purees. While its premium varieties command higher prices — a jar of natural food is about $0.40 more than the conventional product, and a jar of organic food is at least $0.60 more — many consumers have been willing to switch. These strategies have helped Beech-Nut gain market share against competitors and grow dollar sales since 2015, according to IRI data.

The signs point to this being a big part of the baby food business's future. Dahlen said, "If you look at our naturals business and organics, those businesses are larger than the classics. We're well on our way to that transformation."