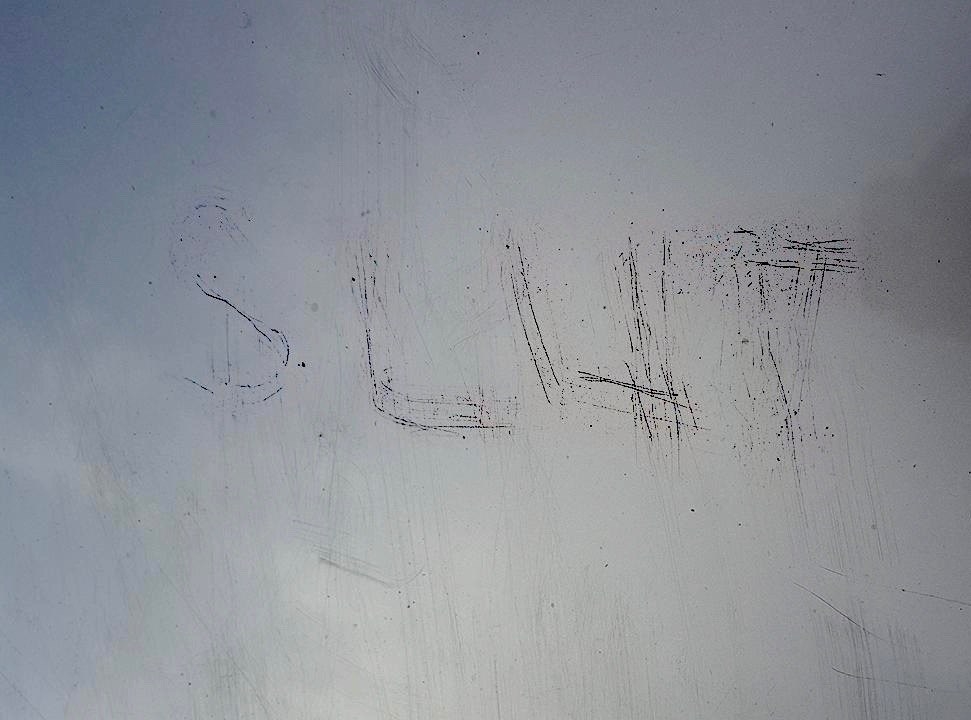

A little after 3 a.m. on Oct. 23, Whitney Ralston called the University of Richmond police to report that someone had carved the word “slut” on the roof of her car. Two days later, Ralston called them again to report more damage to her car and a Facebook message telling her and fellow student C.C. Carreras, “you both are very nasty and should just keep your mouths and legs closed.”

Ralston and Carreras each reported to the university that they were sexually assaulted last year, and they both went public in September, detailing their frustrations with how the school handled their cases. Since then, the two students say, they have received a barrage of harassing messages online, calling them “lying sluts” and “tramps.” The harassment recently escalated to vandalism of their property.

“I think people really forget that we are real people,” said Carreras, a senior at the university. “I am a real 22-year-old girl with real feelings, who’s really affected by this. Just because we’re speaking out publicly about what happened doesn’t mean we’re perfect and we’re healed.”

The backlash Ralston and Carreras experienced captures one of many reasons why sexual assault victims rarely report their attacks — to college officials, police departments, or otherwise. First, they felt let down by their university’s response. Now, they’re facing more abuse.

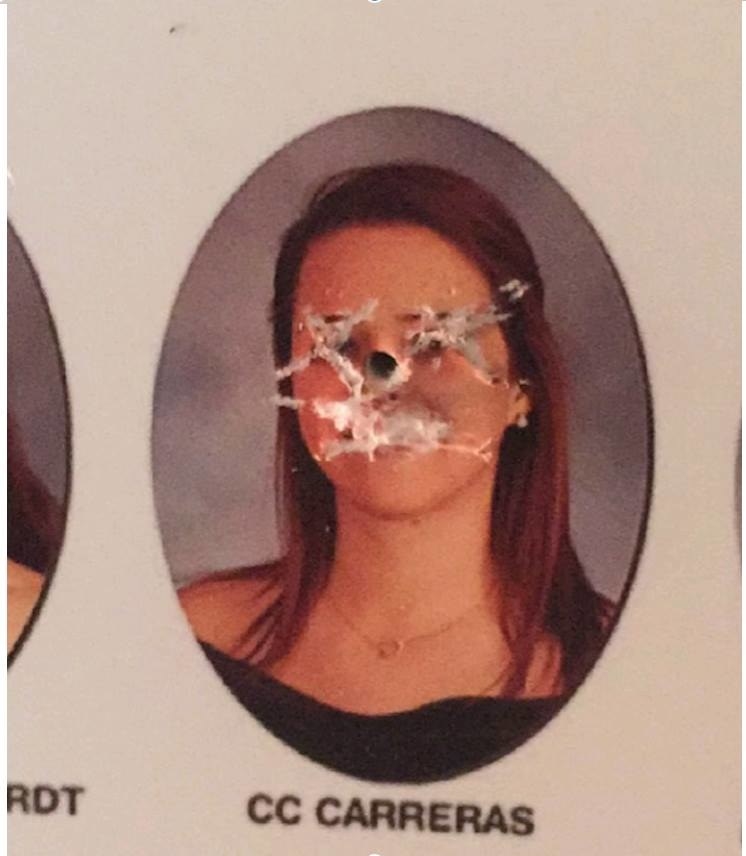

"What about me and me sharing my story affects you so negatively that you need to gouge my eyes out?"

“It’s nothing that’s surprising to us at this point, it just kind of keeps going,” Ralston, a junior, told BuzzFeed News. “We get [harassing messages] at least every day. In the beginning, I just deleted them, but now I’ve been reporting every single thing to police.”

The country is paying more attention to sexual violence than ever before. It’s become a top issue for the White House, was spotlighted at the Oscars and in multiple critically-acclaimed documentaries, and is now a major discussion in the 2016 election, thanks to comments by and accusations against Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump, and resurfaced allegations against Bill Clinton.

A dozen women came forward last month to publicly accuse Trump of sexual assault and making unwanted advances over the years. Trump has denied all of the accusations. Both he and his defenders have suggested the accusations couldn’t be true because the women waited so long to say anything. Trump has threatened to sue the accusers and called them “horrible people” to supportive booing from his voters, who say the women “need to grow a set.” He suggested that one of the women was not attractive enough for him to have groped. Those accusers have faced harassment and ridicule since coming forward — one even says she’s planning to flee the country due to safety concerns.

But according to experts, rape victims’ advocates, and women like Ralston and Carreras, it doesn’t take going after someone as prominent as Trump to face retaliation, and it’s a big reason why many survivors never come forward.

“I’m not really living. I’m stuck inside my house all day and can’t go to class,” Ralston said. “It’s rough.”

Ralston is considering transferring to another college. The majority of her classmates are supportive, Ralston said, but there is a “vocal minority” who are making a normal life in college impossible for her.

When Carreras published a blog post about her experience, she expected classmates to whisper behind her back, glare at her on campus, or unfriend her on Facebook. But she didn’t expect hate mail. She began sobbing in the library when she received one that called her a “cunt,” instructed her to “shut the fuck up,” and to “own up to some bad sex and move on.”

In recent weeks, Carreras’s car was keyed, like Ralston’s was, and she discovered her photo defaced in a composite for her sorority in someone’s apartment. She quipped in an interview with BuzzFeed News: “What about me and me sharing my story affects you so negatively that you need to gouge my eyes out?”

Fear of not being believed or of being blamed for their assaults often plays into why 90 percent of survivors on college campuses never report, said Lisae C. Jordan, executive director of the Maryland Coalition Against Sexual Assault. Considering that statistic, Jordan said, “It’s fascinating to hear people judging women and men who don’t report sexual violence, because that’s most of them."

It’s a common worry, even though federal law prohibits retaliation against a person who reports sexual assault. According to the National Crime Victimization Survey, 20 percent of female rape victims age 18–24 do not report their assaults due to “fear of reprisal.” A 2015 survey of students at 27 universities found 36 percent did not report their assaults because they were “embarrassed, ashamed or that it would be too emotionally difficult.” The only research looking at whether backlash actually occurred deals with the military: Three-in-five victims in a 2016 RAND survey said they experienced retaliation after reporting.

In one recent case at the University of North Florida, a student — who asked to remain anonymous for this story — reported to campus police that another student, Jordan Wilson, threatened her on an elevator on Jan. 20, 2016. Earlier that month, she had initiated a school judicial process against a friend of Wilson’s, who she said sexually assaulted her in September 2015.

“The next time you fuck over one of my friends you better watch out,” Wilson said, according to a police report. When an officer interviewed him, body camera footage shows, Wilson confirmed he was on the elevator with her, that it was the first time he’d ever spoken to her, and admitted to making the “watch out” statement. He said he “could not recall” if he used an expletive.

“I was pretty nervous,” the female student told BuzzFeed News about the incident. “I didn’t know what he was going to do.”

Wilson told the cop that his friend — the accused student — had shown Wilson a photo of the alleged victim on Facebook earlier that day.

A university hearing in March found the accused student not responsible for sexual assault, but guilty of providing alcohol to minors, according to University of North Florida documents. A separate hearing that month found Wilson responsible for harassment. His punishment? Probation and writing an essay, documents show. The female student felt it became impossible to stay on campus, and she transferred to another school at the end of the spring 2016 semester.

“I felt like I had wasted my time and gone through so much stuff, like I could’ve just kept my mouth shut and it would’ve been better,” she told BuzzFeed News.

In October 2013, a female undergraduate from Salisbury University in Maryland reported to the school and the local sheriff’s office that she was sexually assaulted at a house party by a male student, Austin Morales. According to documents submitted in court, she didn’t remember much from that night, other than coming to in a bedroom surrounded by men, with her underwear missing. A school investigation determined it was more likely than not that she was too intoxicated to have consented to sex — her blood alcohol content tested 0.128 the morning after the alleged assault . A hearing found Morales and two other unnamed men guilty of sexual misconduct.

As many male students accused of sexual assault have done in recent years, Morales filed a lawsuit against the university claiming he was wrongly and unfairly suspended. But Morales also took aim at the accuser and her roommates, suing them for defamation and conspiracy for reporting the sexual assault in the first place. He demanded $75,000, plus punitive damages and attorney’s fees.

“This was a very disturbing case,” said Jordan, the head of the Maryland Coalition, which helped with the woman's legal defense. “You have a survivor who bravely came forward, had a sexual assault exam, spoke with police, decided to go forward with the college justice system, which made findings against the other students involved. She was ready to go on with her life and suddenly she gets sucked into a very difficult piece of litigation that ends up in federal court.”

"It made my life 10 times harder than it already had to be."

The Salisbury victim told BuzzFeed News she’d only spoken with her roommates, parents, and girlfriend about being sexually assaulted. To this day, her brothers don’t even know what happened. Since the case was handled internally by the school and never publicized, she was shocked that she now had to defend against a lawsuit.

“I honestly couldn’t believe it,” the woman told BuzzFeed News. “I was 19 when I found out about it. I’m a student, I work six jobs at school to pay for rent; I don’t have money to pay for a lawyer. I had no idea how I was supposed to move on.”

A federal judge dismissed all defamation charges against the women in August 2015, but not before several months of headaches and legal back and forth. (The university later settled the remaining portions of the suit on undisclosed terms.) The woman spent about $10,000 on legal bills, she said. It’s difficult to calculate the mental strain it took dealing with a lawsuit while trying to stay active on campus, like working 18 hour days as an orientation leader.

“That took the biggest toll on me. It was taking away from what I loved to do,” she said. “I wasn’t able to live my life. It made my life 10 times harder than it already had to be.”

Wilson and Morales did not respond to requests for comment for this article. Neither was charged criminally in connection with these cases.

None of these students who spoke to BuzzFeed News regret reporting that they were assaulted, they said. Richmond student Carreras takes solace in how many people contacted her after she went public, some from as far away as California, to share their own experiences.

Still, said Jordan from the Maryland Coalition, “When you look at some of these retaliation cases, where survivors are dragged through court for many months, if not years, after reporting, it’s understandable that most never report. It’s going to take widespread societal change at every level to fix that.”