In October of 2010, a paper came out in the Journal of Computational Science that claimed to be able to predict the stock market with Twitter. There was more to it than that, of course, but the bottom line was a claim to 87% accuracy in predicting day-to-day movement in the Dow Jones Industrial Average, with nothing more than an endless sea of tweets. If true, it was a billion dollar finding (trillion? gajillion?), enough to launch a whole generation of hedge funds, all courtesy of an Illinois computer scientist named Johan Bollen.

The results have been less than stellar.

The first fund to bet big on Bollen's findings was Derwent Capital's so-called "Twitter Fund," arriving in July of last year. In their first month, they beat the market and enjoyed no small amount of buzz. Less than a year later, they quietly shut down, amid persistent rumors of how much they used Bollen's research at all. The 87% figure shows up on lots of mildly sketchy finance sites, but if anyone could actually live up to it, they'd be a billionaire in a matter of days — and, more importantly, you'd be able to feel the financial shockwaves a mile off. Bollen's Guidewave Consulting business is still alive and well — confidentiality agreements prohibit them from revealing who their clients are, or how many remain — but so far, no one's making money off Twitter except Twitter.

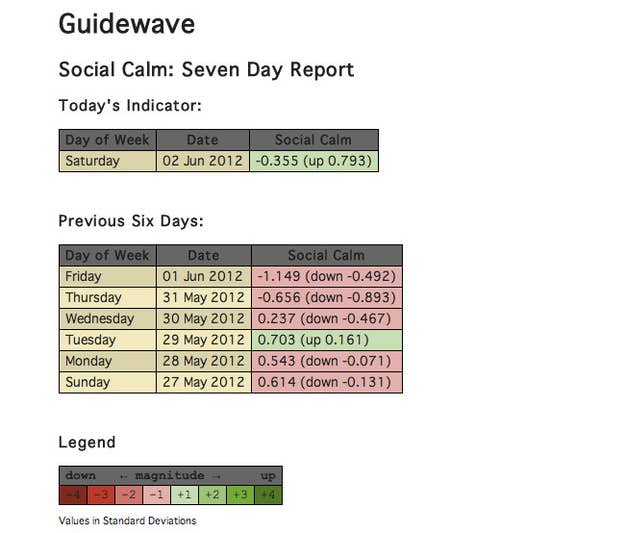

This is what a Guidewave projection looks like, assembled from the Twitter API and an algorithm that ties certain words to certain sentiments. In this case, it's a map of how calm Twitter was feeling in the last week of May, as the market started to crater. You might even say it leads the cratering a little bit, since the biggest drop came on May 31st — but that's exactly where one gets into trouble. Bollen insists, it's not a prediction machine. Instead, he told me, "What you have is a big information-processing device that uses people as very complicated, very sophisticated sensors of real world conditions."

This isn't how sentiment analysis usually works. The more conventional tactics approach the market one stock at a time, like most financial analysis. They deal in specific information like earnings reports or customer sentiment. How much of an impression did the latest jobs report make? Are people excited about a smaller iPad, or already rolling their eyes? These questions have real market consequences, and if Twitter can tip you off to an underwhelming feeling around an upcoming product launch or earnings report, that can be worth a lot of money.

Chris Malloy of the Harvard Business School specializes in the more specific kind of sentiment mining, which has already gained a following among more forward-thinking hedge funds. But when I asked Malloy about searching for broader sentiments, unhinged from particular stocks, he was less optimistic. "I can't imagine how a bunch of people being happy in the morning can help you predict the stock market."

Bollen disagrees: "If you have 100 million people, and they're 2% happier than they were yesterday, that's of tremendous interest." It just depends on what you're looking for.

The idea of tracking market moods has been hovering around the edges of economics for centuries, so it's hard to dismiss entirely. As far back as John Maynard Keynes, economists have made reference to the "animal spirits" of the market, decisions based on, "spontaneous optimism rather than mathematical expectations," as Keynes put it. At best, it boils down to something like the Consumer Confidence Index — not exactly a stock predictor, but the kind of helpful reference point Bollen is hoping to provide. At worst, it becomes an analytic bogeyman, a catchall explanation for otherwise inexplicable twists of the market. If you stare at the S&P sparkline for long enough, it's hard not to think of it as a living, emotional entity.

I've felt the same sense of volatility on Twitter, and I suspect I'm not alone. A full enough feed will swing from outrage to absurd humor to resigned sadness in a matter of seconds, and it's very tempting to read into why. As the Supreme Court's ACA ruling broke, my feed was moving too fast to read, and the frantic energy wasn't limited to my Tweetdeck. Suddenly, I was tapped into what thousands of people were feeling on a moment-to-moment basis. Surely that's worth something, right?

Maybe, maybe not. There are all kinds of selective sampling bias in play, both from the rarefied sample of Twitter users and the kind of sentiments that fit into a 140 characters. Bollen's still plugging away, but anyone looking to cash in had better be ready to wait a few decades. "We're still establishing that these effects actually exist," Bollen put it. "We're not really modeling how this happens, we're trying to measure whether it's happening it all."