Jaron Lanier is best known for coining the phrase "Virtual Reality," but that doesn't really give a sense of how truly unusual he is amidst the hoodie-cloaked tech scene. He's trained as an assistant midwife. He released a major-label neojazz album, in which he plays a Laotian flute. He also plays the oud. In interviews, he says things like, "we've sworn allegiance to a dwarf world, rather than to a giant world." His day job is working on the Kinect, and the idea of him sharing a workplace with Steve Ballmer amuses me to no end.

More recently, he's been thinking a lot about capitalism. He laid out a plan this week at the Personal Democracy Forum that would fix the real world by hitting the startup world at its most vulnerable point: user data.

The story starts with the usual concerns of progressives: American democracy is built on the middle class, but the middle class is disappearing, and the institutions that once sustained it, like pensions and unions, are on their way out. So Lanier wants to create a new institution to sustain the middle class, a kind of pension plan built on the foundation of selling data.

It would work like this: everything on the web stays public, but the moment someone wants to copy something from the web to their computer, they'll be charged a prearranged fee — some small fraction of a cent. Further copying traces back to the creators, like royalties in music or film. Hopefully, after a few decades of laying down data, you'll have an income stream to rival Social Security, courtesy of Big Tech and Big Data.

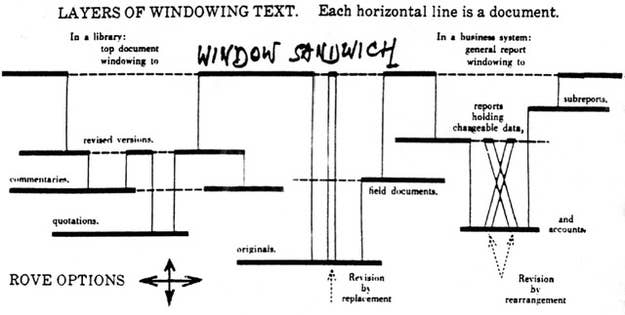

The origins of the idea start all the way back in 1960, when hyperlink pioneer Ted Nelson was laying out his vision of the web. Nelson was worried about copyright, so he engineered a system of two-way hyperlinks that would allow for micropayments to trace back to the origin of any link. The web ended up working on a different, one-sided kind of hyperlink, but the playbook is still there, with lots of ideas for how to implement something like this.

Making it happen would still be difficult. (That's putting it diplomatically.) As anyone in the newspaper business can tell you, getting people to pay for links is harder than it sounds. It's even harder when you're trying to get that money out of the most powerful tech corporations in the world. But even if it doesn't change the world, Lanier's plan reveals a lot about the tech industry's reliance on free data.

One key example is Google Translate. It was built in part by compiling as many freely available translations as possible, then using machine learning technology to build an algorithm from the patterns between them. As far as the law is concerned, the resulting code belongs entirely to Google, but Lanier sees it as a collage of data from translators all around the world, each of whom would be due a few fractional cents. If you include the user data harvested every day on the social web, the figures start to add up. A lot of the major projects of the past decade are built on turning the data glut into a marketing edge: Google AdWords, Facebook, and the whole Big Data sector, for a start. They'd all have to carve out a slice of revenue, and there's no guarantee they'd survive.

It bears repeating: This is not going to happen. Still, if you remade social media with an eye towards the famous you-are-the-product complaint, this is what it would look like. We even know how to do it. The current web may not be built to funnel payments back to the people who made things — just ask Readability — but we're free to rebuild it any time we like.