In the world of high finance, boozy dinners are par for the course. At Pierpoint, Industry’s fictional investment bank, keeping wealthy clients happy is of utmost importance. So when Harper (Myha’la Herrold), a provisional hire trying to net a permanent position at the bank, is invited to her first client dinner, she leaps at the opportunity. Her supervisor Daria (Freya Mavor) leaves her to settle up the bill with Nicole (Sarah Parish), the foul-mouthed brassy lush they’re trying to court.

Nicole offers Harper a ride home in her private car. She sits in silence for a while as Harper discusses a trade she mentioned at dinner. Then Nicole suddenly leans in and asks if she can come a bit closer. Harper laughs nervously. Nicole rests her head on Harper’s shoulder and then grabs her crotch. Harper freezes. “This weird thing happened at dinner with this woman,” Harper later confides to a coworker. “The client, she gave me a ride home and she sort of touched me. And she’s a woman, you know, but it was still kind of weird.”

In Season 2 of Industry, which concluded this summer, we learn that Nicole’s behavior is a pattern. She pulls a similar move, right down to the assertive crotch grab, with Harper’s friend and coworker Robert (Harry Lawtey) and, perhaps most distressingly, with another young provisional hire, who attempts to report the crime to higher-ups and is rebuffed.

Industry isn’t the only HBO show to feature inappropriate workplace relationships between women. While this character’s uneasy machinations aren’t illegal, they are arguably unethical. In Season 2 of The White Lotus, hotel manager Valentina (Sabrina Impacciatore) has an obvious crush on her direct report Isabella (Eleonora Romandini). She buys her a brooch. She finagles to have Isabella’s desk partner Rocco moved to the beach to stop him from flirting with her. And she invites Isabella to an intimate birthday dinner for the two of them until she finds out Isabella is engaged to Rocco. Eventually, she finds comfort in the arms of Mia (Beatrice Grannò), an enterprising musician, who suggests that if Valentina lets her play piano at the hotel restaurant, she’ll return the favor with sex. Valentina takes her up on her offer.

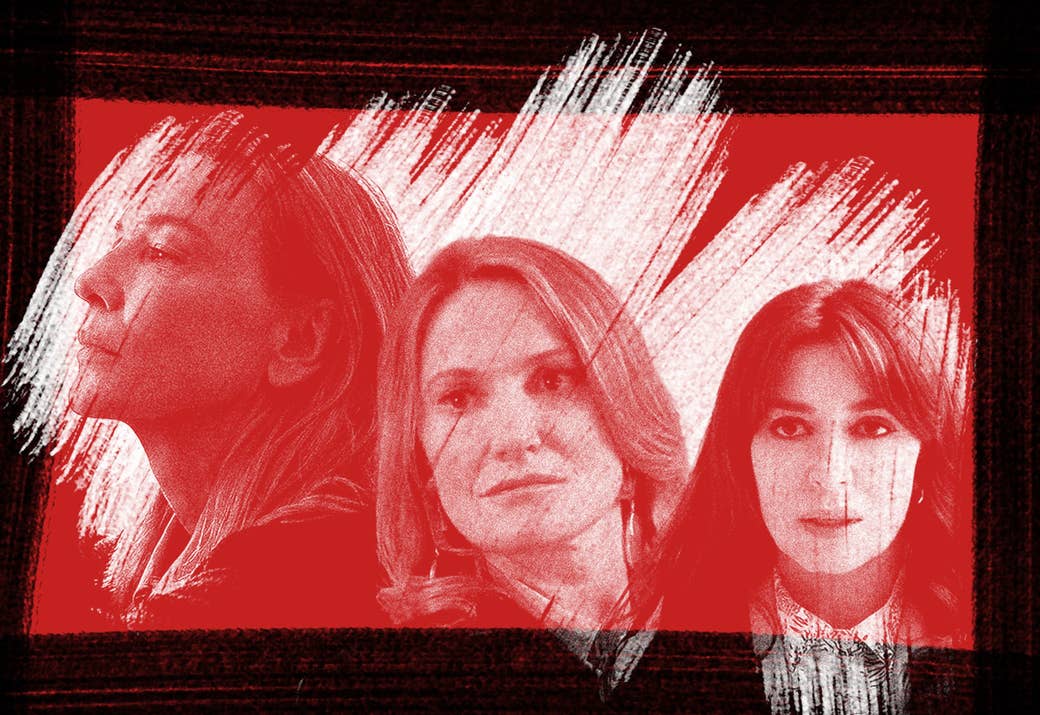

And then in the film world, there’s Tár. In Todd Field’s sure-to-be Oscar-nominated drama, Cate Blanchett plays a critically acclaimed classical conductor with a penchant for giving overwrought speeches about identity politics that sound suspiciously like the grumblings of the middle-aged white man who wrote the movie — and also for engaging in inappropriate sexual relationships with her young subordinates. That pattern plays a role in her eventual professional downfall.

All three of these character arcs, written by men, about women who abuse their varying degrees of power, are an interesting development five years out from when news of Harvey Weinstein’s abuses first broke and the #MeToo movement was unofficially born. Films about the #MeToo era — including 2019’s The Assistant, about a young studio assistant dealing with a Weinstein-like boss; 2020’s overwrought Promising Young Woman; and this year’s dutiful She Said — have tended to focus on familiar storylines about powerful men who misuse their power and women who are trying to hold these men accountable, often unsuccessfully, for their crimes. In the immediate aftermath of #MeToo, much of the focus was on Bad Men and the maddeningly long list of men in power who exploited and abused people with less power. “Believe women” became a popular Twitter refrain.

But the truth has always been more complicated than that; the capacity of power to corrupt holds true regardless of race, gender, or sexual orientation. And in 2022, storylines about bad women, at least in fiction, are coming to the fore.

The brilliance or — depending on your point of view — great irritant of Tár is the degree to which the film steadfastly remains in Lydia Tár’s POV. With the exception of the very beginning, in which an anonymous person appears to be filming Lydia as she sleeps on a private plane, we are immersed in Lydia’s perspective completely. We witness her getting fitted for her bespoke suits. We see her chatting with the New Yorker’s Adam Gopnik about her storied career.

Such a myopic perspective makes it harder to piece out what exactly Lydia did wrong, though it’s clear she did something sexually inappropriate. We slowly learn what may have happened through dream sequences, emails, and eventually a news story. It appears that Lydia once worked closely and had a sexual relationship with a young woman conductor in her mentorship program named Krista. At the beginning of the movie, Krista, we learn from emails, though we never see her onscreen, is desperate to get in touch with Lydia; Lydia warns her assistant Francesca to avoid her at all costs. Krista later kills herself and Lydia’s misconduct eventually goes public, thanks to Francesca, who resigns after learning she will not be receiving a coveted assistant conductor position.

The last third of the movie seems almost dreamlike, and some have argued that it is in fact a dream, or more accurately a nightmare. Lydia’s reputation sinks and her career goes into freefall as news disseminates about her inappropriate sexual relationships with young women.

Lydia is aware of the foibles of her predecessors; her mentor, it’s implied, had a sex scandal of his own, and history is ridden with abusive artists (Lydia even name-checks a few). Yet even knowing all of this, Lydia appears addicted to exploiting her power. Even as Lydia is dogged by Krista’s ghost — she hears phantom noises and can’t sleep at night — she still sets her sights on a young cellist named Olga. Lydia changes her initial comments on Olga’s blind audition once she recognizes the young woman’s boots, having seen her earlier in the restroom. Lydia offers her a coveted solo, a kind of favoritism that seems second nature to her.

Ultimately the film is so besotted with Cate Blanchett’s Lydia — her composure, her accolades — that it inevitably draws sympathy toward her. She’s successfully “canceled,” banished to an unnamed Asian country to conduct an orchestra playing the soundtrack to Monster Hunt. It’s a dark joke, or maybe it’s all in Lydia’s head, but the point is that it’s her experience we see so clearly. She’s not a clear-cut hero, obviously, but by virtue of the time we spend with her — almost two and a half hours of Blanchett, who appears in virtually every frame — her perspective is prioritized at the expense of any significant thought or care given to her victims.

In Industry, Nicole isn’t the only woman with work practices that are troubling at best. In the second season of Industry, Yasmin (Marisa Abela), a publishing heir who received habitual sexual and verbal abuse from her old boss, is drawn to Celeste (Katrine De Candole), an enigmatic older woman who works in private wealth management. They meet when they’re both buying cocaine from the same dealer. Yasmin wants to bring her father on as a client in the department. He’s a sleaze — Celeste mentions that he hit on her once at Art Basel, but she wonders if he would even remember her. She tells Yasmin that three of her clients were featured in Jeffrey Epstein’s black book. But that doesn’t stop her from committing her own sexual indiscretions by sleeping with Yasmin, her direct report, mere days after Yasmin formally joins her team. After Yasmin, learning of her father’s own sexual misconduct, decides that she doesn’t want him as their client anymore, Celeste informs her that that won’t do. “I’m too old to work with crusaders. It’s exhausting. The status quo works for us,” she says. And then she reminds Yasmin that she is replaceable.

In the world of Industry, written by former investment bankers Mickey Down and Konrad Kay, there’s no place for heroes. Each woman looks out for herself—cogs in a well-established system. Even Yasmin, the recipient of so much verbal and sexual abuse from her boss, has no heart for the young grad who comes to her in distress about her experience with the lecherous Nicole.

“Assault is a sliding scale,” Yasmin tells the young grad. “Look, cynically this might even help you. You strike me as pragmatic.” In that sense, Industry’s examination of power is a more recognizable one.

In The White Lotus, ultimately, the resolution of Valentina’s arc appears somewhat sweet. She comes into her sexuality, and Mia gets to play the piano. But if Valentina had been a man, would that storyline be as endearing or would it just be creepy? There are no clear answers.

None of these fictional works negate the fact that in real life, women who credibly accuse powerful men of abuse continue to be maligned and condemned online. Ghislaine Maxwell, sentenced to 20 years in prison for her role in facilitating Jeffrey Epstein and his ilk’s habitual abuse of several victims, is the closest thing to a high-profile woman predator, and even then, her aims were in service to a man.

But they are reminders that when it comes to sex and the misuse of power, gender essentialist assumptions that only men are capable of such cruelty are misguided. Power is one hell of a drug, and women often haven’t had the opportunity to abuse it. ●