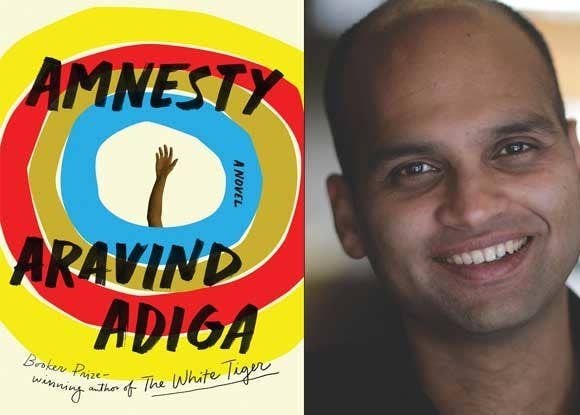

Amnesty by Aravind Adiga

All around the world, richer nations — whose foreign and economic policies have often, at least indirectly, been responsible for creating the dismal conditions that force people from developing countries to flee — are grappling with an influx of immigrants.

Australia is no exception. One of the richest countries in the world, its detention centers — Villawood and Christmas Island among them — are famous for their brutality.

Fear of ending up in such a detention center is what constitutes the dilemma at the center of Aravind Adiga’s new novel Amnesty. Danny is an undocumented man from Sri Lanka working as a cleaner in Sydney. When he gets news that a former client of his has been murdered, he has a sickening hunch who the murderer might be. Over the course of one day, Danny grapples with whether he should turn in the prospective murderer, a rich Indian-born Australian who knows Danny’s status, and risk deportation.

While the subject matter is serious, Adiga, whose 2007 debut The White Tiger won the Booker Prize, writes in a whimsical, somewhat irreverent style. Danny has plenty of observations to make about his adopted country: “Danny divided Sydney into two kinds of suburbs — thick bum, where the working class lived, ate badly, cleaned for themselves; and thin bum, where the fit and young people ate salads and jogged a lot but almost never cleaned their own homes.”

He’s particularly effective at calling out the class distinctions between Australian-born brown people, like the victim and the murderer, and people like Danny: “...the ostentatiously indifferent I’ve got nothing in common with you, mate glances of the Australian-born children of doctors in Mosman or Castle Hill (Icebox Indians Danny called them, because they always wore black glasses and never seemed to sweat, even in summer).”

Adiga is adept at bringing out the inherent absurdity of these distinctions — “Illegal means legal who is ill, no?” — and it’s the black comedy that lingers as the story races toward its inevitably bleak conclusion. Get your copy now. —Tomi Obaro

The Glass Hotel by Emily St. John Mandel

Emily St. John Mandel’s writing is something to luxuriate in. This sounds hyperbolic, but she writes the kind of prose that makes you want to pick up a pen while reading to underline the sentences that catch your breath — which can be found on just about every page. Her newest novel, The Glass Hotel, is no exception.

The book's intricate plot is nonlinear but generally centers around the unraveling of a massive Bernie Madoff–esque Ponzi scheme and a large collection of characters connected by the fraud. Among others, there's Jonathan Alkaitis, the businessman behind the crime; his young girlfriend Vincent who meets Alkaitis while bartending at a luxury hotel in the wilderness outside Vancouver (the titular establishment); Vincent's half-brother; a series of ill-fated investors; and Alkaitis's employees, who narrate the accelerating downfall of the Ponzi scheme as if it were a Grecian Drama in a particularly wonderful section of the book entitled "The Office Chorus."

While there is something dreamlike about the ambience Mandel creates in The Glass Hotel — the novel isn't exactly escapist. One of Mandel’s strength as a writer is her ability to turn implausible scenarios into something that feels immediate and real — perhaps even better illustrated in her last novel, the National Book Award Finalist Station Eleven in which Mandel follows survivors in the aftermath of a sickness that wipes out a majority of the world’s population.

So it's probably incorrect to say that this book (or Station Eleven...obviously) would be a comforting read in the midst of self-isolation and social distancing. But in a book about greed and loss and loneliness, Mandel has also crafted a distinctly relevant story about the strange invisible threads that connect us, and the dizzying understanding that there are infinite paths our lives can take — all of this culminating in the simple fact that Mandel is a storyteller at the top of her game. Get your copy. —Jillian Karande

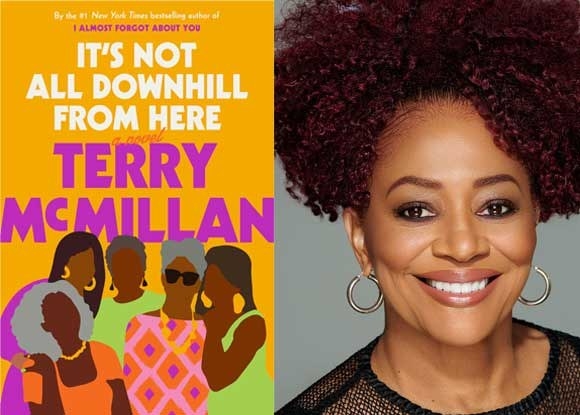

It's Not All Downhill From Here by Terry McMillan

If there's one person whose books fully encompass what it means to have a thorough, unbreakable bond among friends, it's Terry McMillan. In her latest novel It's Not All Downhill From Here, Terry tells the story of Loretha, a middle-aged woman dealing with the unexpected loss of her beloved husband, Carl, the grueling realities of aging, a life-changing diabetes diagnosis, and the dysfunction that comes with family and friends. In the midst of grieving, Loretha, or "Lo," finds herself taking on the responsibility of everyone around her. From an estranged daughter who pushes Lo away whenever she gets too close, to a best friend who's on the brink of ruining her marriage — no matter what, Lo is reliably the person they can always count on. Unfortunately, sometimes she forgets to pour that same love and dedication into herself.

With helpful reminders from her sincere tell-it-like-it-is friends and family, Lo quickly learns there isn't any battle she has to face alone and that getting older doesn't have to be something you dread, especially when you have people to do it with.

McMillan drew me in with her relatable language and characters, but it was the familiar storylines that really hit home for me. I couldn't help but think of my mother and other black women as I read about Lo and her superwoman complex. The emotional burden they carry around with them while taking on the world truly astonishes me, which is why I couldn't put this book down. Not only would I recommend it to others, but I already handed it off to my mom for her to read next. Get your copy now. —Morgan Murrell

Real Life by Brandon Taylor

Wallace is a black, queer, chubby, and introverted student attending a graduate science program in the Midwest. In other words, he’s a character who doesn’t get featured in a lot of campus fiction. In Brandon Taylor's debut novel Real Life, though, it is entirely through his eyes that we witness one notable weekend with his friends and colleagues (And campus birds?? There are so many birds.) play out.

Much to my surprise, there is actually a lot of social drama — not just microscopic worm-related drama — to be mined within the academic bubble of biochemistry. And I’m talking about the world that exists outside of the pages of this book, too. Taylor, who, prior to becoming a writer, was a biochemistry researcher, has spoken openly about being motivated to write this book after observing the “catty politics” of research labs.

Taylor, also like Wallace, is black, queer, and comes from a working-class background in Alabama. His personal struggles with being the only black person in his program and constantly dodging microaggressions (and some just blatant aggressions — you will know which I’m referring) are also Wallace’s personal struggles.

Real Life brings to mind the will-they-won’t-they dynamics of Hanya Yanagihara’s 2015 novel A Little Life’s twentysomething friend group. It also feels like an unexpected companion piece to psychologist Alan Downs’ 2005 nonfiction book Velvet Rage, about growing up gay, and which also investigates the gay man’s strained relationship with his father. (The relationship between Wallace and his recently deceased father looms large here.)

Taylor’s obsessive habit of detailing physical landscape can feel tedious at times and his dialogue is occasionally stilted. But with the knowledge that this is only Taylor’s first published novel, it’s hard not to get excited about the stuffy and homogenous worlds he might explode in his follow-up efforts. I’ll keep an eye out for him. Get your copy now. —Colin Gorenstein ●