Steve Sederwall peers down at a rectangle of dark wood flooring. The panel, which sits at the top of a steep, dark staircase, is probably oak or pine, and it’s been here since 1874, when this two-story adobe courthouse in the Sierra Blancas — the mountain range that rises through central and southern New Mexico — was built. "We sprayed the luminol right here," Sederwall says. He's talking about the chemical compound made famous by the techno-minded crime drama: When its yellowish crystals are applied to even trace amounts of blood, the hemoglobin produces a stunning blue glow.

At 63, Sederwall is a big man with a goatee, a garrulous disposition, and a drawl made raspy by a nasty cough. It’s a bright Thursday afternoon in April, and as he recalls the Sunday 12 years ago when he was a reserve deputy with the Lincoln County Sheriff’s Office watching this floorboard ripple with color, he excitedly veers into the 134-year-old backstory that led him here. There was the newspaper account from 1890. There was the book from 1936. They offered firsthand information about one of the most sensational events in the history of the American West — the double cop killing and jailbreak committed on April 28, 1881, by a skinny, buck-toothed young man named William H. Bonney, who was known by various aliases during his brief life, but in death would be known forever as Billy the Kid.

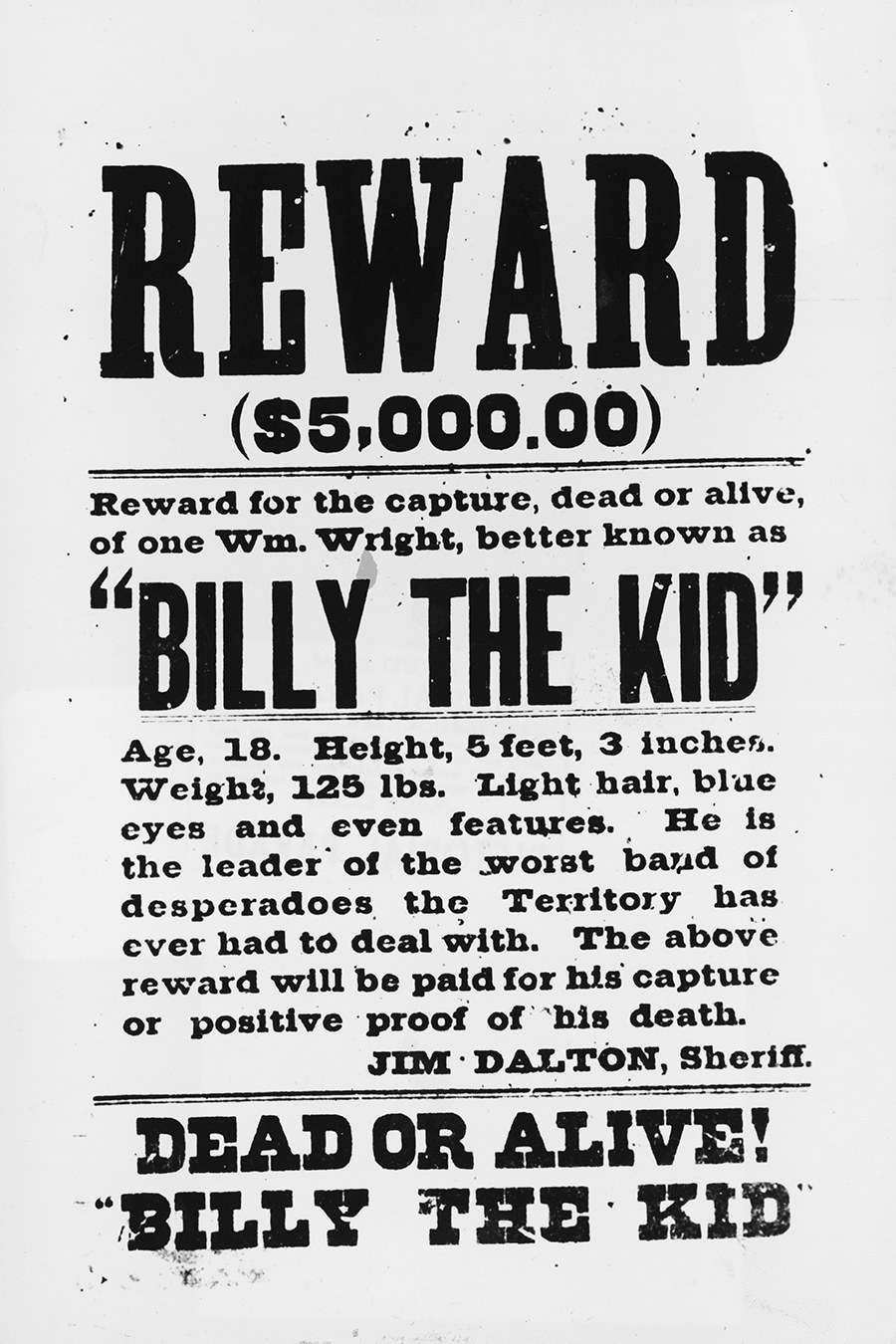

Bonney was among the most notorious celebrity outlaws of the West, someone who briefly thrived amid the lawlessness of 19th-century New Mexico. Some newspapers of the day portrayed Bonney as a knuckle-dragging murderer — he was said to have killed a man for every year he lived, supposedly 21 — though history cut a far more complex portrait. His most sympathetic admirers offer him up as a charming, whip-smart idealist, a Robin Hood–like folk hero who fought with righteous passion during the Lincoln County War.

A few months after Bonney’s jailhouse escape, the Lincoln County sheriff tracked the fugitive to a town near the Texas border and shot him dead. In the 134 years since, Bonney has become one of the West’s most mythologized and tragic antiheroes, someone whose “pliable” biography, as the historian Paul Andrew Hutton put it, provided a ready-made Hollywood storyline that attracted generations of followers. Bonney has been the star of dozens of movies — everything from the Young Guns films to the campy Billy the Kid Versus Dracula — probably even more cable television shows and countless biographies. Though the only confirmed photo of Bonney was purchased by one of the Koch brothers for $2.3 million four years ago, National Geographic, Kevin Costner, and a television production crew are exploring claims of a recently discovered, disputed image that, if authenticated, could apparently be the most valuable photo on the planet.

Sederwall says he didn’t care all that much about Bonney’s cult following. As far he was concerned, Bonney was "saddle trash," and Sederwall was in that stairwell for one thing only — to conduct a modern investigation into the murder of J.W. Bell, one of the deputies killed during Bonney’s escape. The logic behind the investigation was simple. "I’m a cop. He’s a cop,” Sederwall explains. “He gets killed. He was a footnote. I’m thinking, Why?"

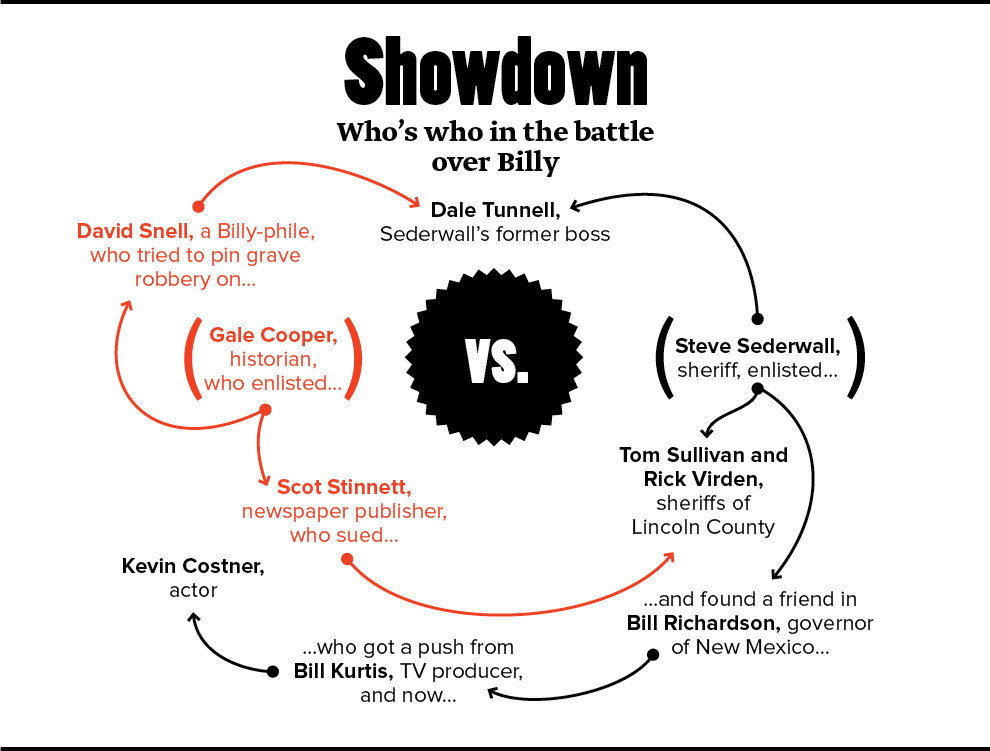

If this had been the private pursuit of another Billy-phile, Sederwall’s detective work may have ended up as a blip in the twisty history of William Bonney. But it wasn’t. It was part of an official homicide investigation backed by two sheriff’s offices, promoted in a History Channel program, given front-page treatment in the New York Times, and championed by then-governor and soon-to-be presidential contender Bill Richardson.

The luminol on the courthouse floor was just one element of that investigation. The sheriffs were also examining one of the stranger storylines of Bonney’s afterlife: the theory that the man who shot Bonney, Pat Garrett, didn’t actually kill him, but helped him fake his own death and escape to Arizona, perhaps, where he lived as a rancher named John Miller, or to Texas Hill Country, where he died in 1950 as Brushy Bill Roberts.

Both of these men claimed to be Bonney long after 1881, and a vibrant subculture of amateur historians, authors, and enthusiasts continues to argue that they may have been telling the truth. In the small Texas town where Roberts died, there’s a storefront museum dedicated to claiming him as the real William Bonney, and his nearby tombstone is framed by a large granite arch with an outsized engraving. "Billy the Kid," it says.

For this branch of Bonney’s devotees, Sederwall’s investigation was huge. It’s not that there hadn’t been efforts like this before: In 1950, the work of a man named William Morrison even earned Brushy Bill a meeting with the governor of New Mexico to request a pardon for a murder indictment that he said he’d been promised as a young man. (He was denied.) But there had never been a modern, state-run operation relying on the latest in crime scene technology. “Nobody had said, let’s prove this — empirically,” recalls Bob Boze Bell, executive editor of the magazine True West. “That’s what was so unique.”

The broader sweep of historians, however, sneers at this subculture. The most aggressive protector of Bonney’s accepted biography is a Harvard-trained doctor and retired psychiatrist who traded her practice in Beverly Hills for a cabin in New Mexico, where, in the late 1990s, she began writing books about Bonney. Her name is Gale Cooper, and in 2003, as the sheriffs’ investigation was getting underway, she challenged every aspect of it. Unlike the sheriffs, Cooper worked behind the scenes — at least at first — to generate opposition, partnering with newspapermen, lawyers, and fellow Billy-philes who were comfortable being in the spotlight. In her emphatic telling, Sederwall, Richardson, and the rest were no more than opportunistic interlopers, the equivalent of global warming deniers operating a state-sponsored con.

The events that followed tracked a tangled and at times unbelievable trajectory, one that hemmed in an ever-expanding cast of characters including everyone from the governor to one of the state’s most prominent open records advocates. The story has played out as a protracted civil lawsuit that currently resides in the New Mexico Court of Appeals, and it has been painstakingly detailed in one of Cooper’s recently updated books, Cracking the Billy the Kid Case Hoax. In print and in court, Cooper has alleged all manner of scandalous activities against her adversaries, everything from pay-to-play politics at the highest levels of state government to grave robbery and records tampering.

But Cooper’s crusade also exposes a dramatic struggle over a question far older than Bonney himself: Who controls history? Is it the “Dead Bandit Society,” as Sederwall mockingly calls the mainstream scholars who accept Bonney’s conventional life and death storyline and who, in Sederwall’s view, refuse to challenge the history they’ve written? Or is it the “hoaxers,” as Cooper calls Sederwall and his noncredentialed comrades?

Dangling in the balance are not only their reputations — Cooper as Bonney’s chief defender, Sederwall as a leading insurgent — but the biography of one the West's most iconic characters and the media machine his life has produced.

I meet Sederwall at a Shell station in Capitan, New Mexico, a village 11 miles west of Lincoln, the setting of Bonney’s courthouse escape and a town that has been preserved as an eerie memorial to Bonney and the Lincoln County War. Today, it’s a massive tourist draw, the most widely visited monument in the state. I hop in the passenger seat of Sederwall’s white Ford pickup, and as we drive toward the courthouse, barreling past juniper-blanketed hillsides, he tells me he grew up far from Billy the Kid country, in Hannibal, Missouri.

By 2003, he’d become the mayor of Capitan and an unpaid volunteer deputy with Lincoln County. (He also co-owns an RV park and runs a private detective agency.) Someone left a book about Bonney at his office — The West of Billy the Kid — and one day he came across a line about the courthouse escape. “It said, ‘Chances are, we’ll never know what happened in that courthouse,'" Sederwall recalls. As he pondered what that meant, in walked Tom Sullivan, the county’s four-term sheriff and Sederwell’s close confidant. (“We’d talk about everything in the world,” Sederwell says.)

Sederwall wanted to “open up a case” about the deputy’s killing, which was somewhat out of character. It’s not like he was an aspiring amateur historian, or even an Old West buff. But he’d always loved being a cop, and running investigations was his retirement pastime of choice. “Everybody else goes out and plays golf,” he says. “I go out and look at dead bandits.”

How would Sederwall do it? By reconstructing some of the most important moments from Bonney’s jailbreak. After Bonney shot and killed Bell, for instance, the second guard was down the road at the Wortley Hotel, feeding the jail's other inmates. When he heard the shot, he dashed toward the courthouse; Bonney leaned out a second-floor window and shot him to death. But could a gun fired inside the courthouse, which had 16-inch adobe walls, actually be heard at the Wortley, about 250 feet down the road? As Sederwall plotted the experiment, Sullivan decided to tag along.

On April 28, 2003, the men stood shoulder to shoulder at the top of the courthouse staircase. Sullivan pointed a .45 Long Colt pistol down the steps and fired two blanks. Sederwall’s hypothesis, it turned out, was unfounded. The shots were heard nearly a mile away.

What happened next set off a series of unintended consequences that Sederwall says reshaped the investigation. Sullivan walked outside and, with his police radio, told the dispatcher he was working a homicide. "The suspect is William Bonney," Sederwall recalls him saying.

Sederwall huffs and chortles as he tells me this. It was nothing more than a flippant joke, but because the local newspaper monitors the police radio, the experiment became an official police matter. From there, he recalls, "all this stuff started going crazy." The Albuquerque Journal picked up the story, and, on June 5, 2003, so did the New York Times.

The day the Times story ran, Sederwall says, his cell phone rang. Gov. Richardson wanted to chat. "The first thing he tells us is, ‘I’ve got a tourism department across the street and they’ve got a $5 million budget and they can’t buy the shit you guys are pulling off,'" Sederwall recalls.

Five days later, the sheriffs, the governor, and a handful of other officials appeared before a throng of reporters at the capitol. The sheriffs, Richardson said, were seeking to "answer key questions that have lingered for over 120 years surrounding the life and death” of one of New Mexico’s most legendary icons.

Richardson was prepared to fully support the endeavor: The state police, the national laboratories at Sandia and Los Alamos, the University of New Mexico — they would all contribute. There would be ground-penetrating radar and the best forensic technology. There would be hearings in Silver City, Lincoln, and Fort Sumner. "Getting to the truth is our goal,” Richardson said. “But, if this increases interest and tourism in our state, I couldn’t be happier."

Sederwall’s story about the beginnings of the Bonney investigation has been mercilessly scrutinized, and much of it is at odds with the record. In the May 2003 edition of the Capitan mayor’s report, for instance, Sederwall didn’t describe it as a project that sought to spotlight the killing of a long-forgotten officer, but as an opportunity to examine the claim that Brushy Bill Roberts actually might have been William Bonney. Nor did his report describe the investigation as something that, through ignorance and accident, became an official matter; rather, it appeared to be an organized effort, one that "will put a positive light on the county, our town, and the state.” Even the governor, during his press conference, said it was Sullivan and Sederwall who reached out to him — and not the other way around. (In an interview, Richardson, who was governor until Jan. 1, 2011, told me he doesn’t recall telling the sheriffs about his flailing tourism agency.)

These may seem minor, a few details lost in the fog of 12 years. But once the sheriffs' investigation had become a thing of perpetual controversy, Gale Cooper would point to these inconsistencies and others as evidence of a cover-up, a self-serving altering of history designed to evade accountability.

Back when the investigation was just beginning, though, Cooper was still a novice in the Billy the Kid scene. With her cowboy boots and jeans, she looked the part of a Western woman, but she’d moved to New Mexico only a few years before. Raised in New York City, she’s a self-described overachiever — a high school valedictorian who joined the prestigious honors society Phi Beta Kappa and, in 1971, earned a medical degree from Harvard. By 1975, she’d settled in California. In Beverly Hills, she ran a psychiatric practice specializing in the effects of violent crime; in a gated community in the San Fernando Valley, she lived in a big house where she bred miniature horses. At Barnes & Noble one day in the summer of 1998, Cooper picked up a copy of Pat Garrett’s The Authentic Life of Billy the Kid. She finished it in an hour. "I said, ‘This is the great story of America,’" she recalls thinking. Mesmerized, she flew to New Mexico and visited Bonney’s grave in Fort Sumner.

Cooper started writing a novel, Joy of the Birds, about one of Bonney’s supposed romances, and revisited New Mexico, this time to get a clearer picture of Bonney’s terrain. "I was changing," she wrote. "Shy, bookish, and reclusive, never having danced, I bought CDs of old-style, Mexican ranch music: music to which bi-cultural Billy would have danced." She came to view Bonney not as an outlaw, but as someone done wrong by history who should instead be remembered as a rebel on a righteous path. "It’s an unquenchable passion," she tells me in a phone interview, adding, "I sold everything I had and moved to a log cabin. That’s where I am now."

This must have been a strange transition: a bicoastal, Ivy League–educated doctor transplanted to one of the poorest states in the country, pursuing an interest that was, as she puts it, "a tangent." I didn’t get to ask Cooper about it in detail, though, because our conversations were limited. When we spoke earlier this year, I told her I wanted to write about her, and she held forth on her "adversaries," on how she "lived in fear of being assassinated," on Bonney’s "unsung freedom fight." She barely paused for a breath. At one point, she asked how fast I could read.

When three of her books about Bonney arrived in the mail a few days later, I knew why. They ranged in length from nearly 600 pages (Billy the Kid’s Writings, Words & Wit) to more than a thousand (Cracking the Billy the Kid Case Hoax). When I called back a few weeks later to see about possibly scheduling a visit, she seemed wary of my intentions and protective of her reputation — of being portrayed as an "oddity," as she puts it. In a follow-up email, she told me perhaps we could talk at some point in the future. When I told her I wanted to pursue the story anyway — and that I at least hoped we could meet — she accused me of "railroading" for an interview. Despite repeated requests to talk, I never heard from Cooper again.

I wasn’t sure what to make of her. Cracking the Billy the Kid Case Hoax was impressive. It’s part diary, part case file, and crammed with "excruciating detail," as she puts it. But it can be distractingly opinionated and hokey. "I learned my lessons as a reluctant whistleblower," she writes in the fourth paragraph of the first chapter. "As my personal danger increased, I persisted. When democracy is imperiled, it is a privilege to protect it."

It might be easy to dismiss Cooper as fanciful or worse, but allies of the investigation had a strikingly nuanced view of her. Jay Miller, a former syndicated political columnist who covered the beginnings of the investigation and later published a book about it, describes her as "one of the most talented people I’ve ever met" and “a retired psychiatrist with all the hang-ups that a psychiatrist would have.” Historian Frederick Nolan put it this way: "No one has been more active, more diligent, and more effective in opposing the machinations of these shameless charlatans than Dr. Gale Cooper."

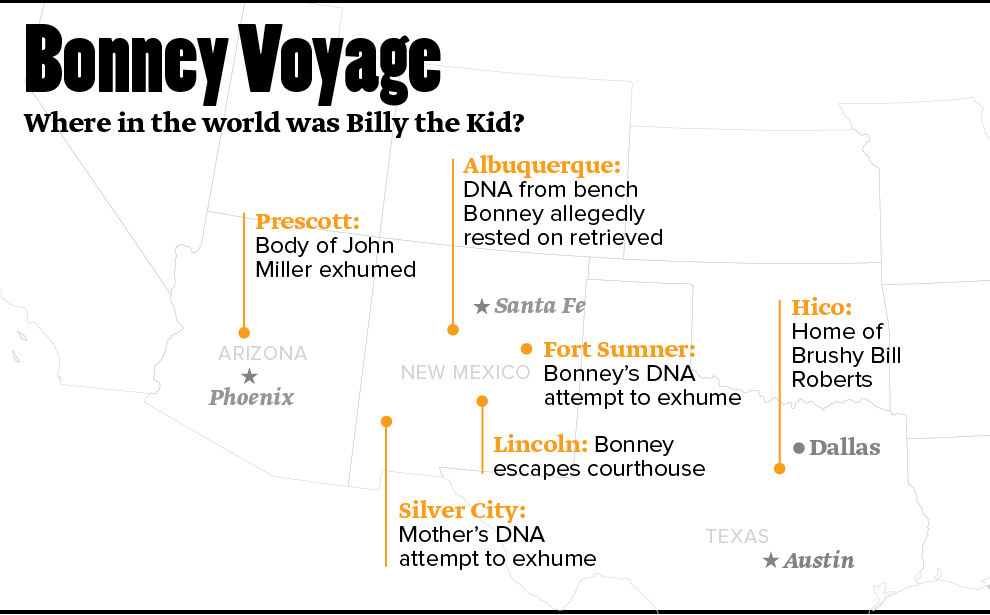

After the press conference, the sheriffs’ investigation churned forward. In Albuquerque, Sederwall tracked down a wooden bench that he claimed Bonney laid on after he was shot, and a high-profile forensic scientist collected shavings from it. In Fort Sumner, a petition was filed to exhume Bonney's body, and in Silver City, the same was done with his mother, whose DNA would provide a reference sample.

It was there, in November 2003, that a lawyer from a large Texas-based law firm appeared to speak on behalf of William Bonney. The attorney, Bill Robins III, had been personally appointed by the governor. A Wild West buff, he wrote that the case represented a “unique moment in jurisprudence,” one “where law, history, legend, myth, and modern criminology come simultaneously to the forefront in a single proceeding.” According to Robins, Bonney supported the exhumation of his own mother, and if Silver City tried to challenge the petition, Bonney planned to challenge the town right back.

Cooper found lawyers to help the fight petition, because in her view, the whole thing was preposterous. As a legal matter, Bonney’s death had been settled since 1881: a coroner’s jury identified Bonney's body the morning after he was killed. What’s worse, she later wrote, is that Robins said he was there on behalf of Bonney’s estate. But there was no estate: Bonney had neither money nor living ancestors. Nor do governors appoint lawyers to represent the deceased. That’s done by judges, or maybe the attorney general, says Robert Scavron, Silver City’s town attorney. “It made no sense,” Scavron says.

Robins, however, was providing the governor with more than unusual lawyering. Between 2002 and 2005, he and his law firm gave tens of thousands of dollars in campaign contributions to Bill Richardson, according to the National Institute on Money in State Politics. In 2004, Cooper also discovered that Robins had underwritten the sheriffs' investigation, at least in part, with a $3,000 check.

The arrangement seemed very shady. Had there been a quid pro quo? Was Robins’ appointment a strange favor for an important donor? “There were so many question marks,” says Jeremy Theoret, a lawyer who, years later, briefly worked with Cooper and tried to determine who was paying the sheriffs and how much they had received. “How can private citizens or deputies open accounts for an official government entity and take money that no one’s accounting for?”

Tom Sullivan, the Lincoln County sheriff, tried to explain during a 2008 deposition. According to a transcript, Sullivan said the governor’s spokesperson, Billy Sparks, “handed me a envelope and he said this is from friends of the governor to conduct your investigation." Sullivan received three checks totaling $6,500, he said, “so we won’t have to spend any taxpayer’s money.”

Richardson calls Sullivan’s account “false” and adds that he did nothing improper for Robins, who was given “an honorary appointment.” (Robins did not respond to interview requests. Sparks also “categorically” denies giving Sullivan money.)

Back in Silver City, the judge, Henry Quintero, punted on the exhumation. He’d consider the petition under one narrow circumstance: If Bonney’s remains were located in Fort Sumner, and if his DNA was successfully extracted, then the sheriffs could return to Silver City with their findings and he’d reconsider the petition.

So focus shifted to Fort Sumner, New Mexico, a small, dusty agricultural town near the Texas Panhandle where William Bonney still retains an outsize presence. At City Hall, a pencil sketch of him hangs on a brick wall. On Route 60, the main thoroughfare through town, is the village’s most recognizable building, the Billy the Kid Museum, which contains, among other things, Bonney’s Winchester rifle, a framed copy of the coroner jury’s report, and a poster-size copy of the photograph being investigated in the Kevin Costner program.

Bonney’s grave, which is a few miles from Fort Sumner, is more suggestion than fact. Scot Stinnett, the owner, publisher, and sole reporter at the De Baca County News, tells me it’s been that way for more than half a century. Two major floods, one in the 1930s and another in the ’50s, had reconfigured the town’s deceased. "You can dig all you want, and you may find bodies," Stinnett says, "but it may not be the body you think is there."

Fort Sumner’s mayor, Raymond Lopez, worried about the consequences of the dig. His village is a poor place; exhuming DNA that didn’t match Bonney’s would damage its prominent spot on the Billy the Kid tourist circuit. So Lopez opposed the exhumation.

Fort Sumner doesn’t have a municipal lawyer, however, so there was no one to challenge the sheriffs’ petition in court. Desperate to fund a legal defense, Lopez organized bake sales and fundraisers, and an account was set up for donations at a local bank. By then, Cooper had come to view herself as a singular force in a fight of “Davids against Goliaths,” as she put it, the only person willing to organize against corrupt authorities to protect Bonney’s “magnificent history.” As Cooper had done in Silver City, she worked behind the scenes, corresponding with the lawyers who took on the case; she also paid for the historian Frederick Nolan’s visit to Fort Sumner.

As the fight lurched forward, the debate over the investigation reached a fever pitch. Gov. Richardson was scolded by nearly a dozen officials and leaders from Silver City in an open letter that June, emphasizing that “every expert historian on the life and times of Billy the Kid has labeled the case as pure bunk."

The History Channel show, which aired in April, presented the conflict as a "range war" between old-school lawmen using modern forensics and nervous officials desperately protecting tourist dollars. At one point, Sullivan and Sederwall appear onscreen, leaning against a wooden fence. "I don’t know why they’re fighting us," Sullivan says, peering toward the camera. "We’re trying to conduct an official criminal investigation.” What Silver City and Fort Sumner were doing, Sullivan concludes, is "organized obstruction of justice."

By late September, the pressure from Fort Sumner got to Richardson. So did a creeping suspicion about the sheriffs. “There was a lot of publicity seeking,” Richardson says. So Bill Robins withdrew the petition to exhume Bonney's body.

But Sederwall and Sullivan weren’t deterred. Eight months later, they took the dig 600 miles west, to an assisted living facility and cemetery in Prescott, Arizona, called Pioneers' Home. They were there to do what they hadn’t been able to in New Mexico: Exhume a body, extract its DNA, and see how the results compared with William Bonney’s accepted history. Along with a television production crew filming the event, the group also included a forensic anthropologist, cemetery officials, a DNA expert, and Sederwall’s former boss, Dale Tunnell.

The pair had worked together at the Bureau of Land Management, where Sederwall was an undercover narcotics investigator. They’d remained friendly over the years, though Tunnell kept a clear-eyed view of his old colleague: While Sederwall excelled in the murky world of borderland drug smuggling, he was also known as a cowboy who craved attention and liked to push people’s buttons. “I had to throw the reins on him," Tunnell says, declining to be more specific. "He’s a one-man wrecking crew. Nobody walks away unscathed."

Sederwall asked Tunnell if he’d look into a theory that Bonney escaped to Arizona, where, three-quarters of a century ago, he supposedly lived as a rancher named John Miller. Tunnell had briefly worked as a deputy sheriff in Lincoln County in 1976, so he was familiar with the local history. But he wasn’t a buff. Still, he agreed to help Sederwall and came to believe John Miller was Billy the Kid. "William Bonney was not shot and killed the way everyone thinks he was," Tunnell says. "There was a cover-up."

Tunnell’s research led them to Pioneers’ Home, where Miller died on Nov. 7, 1937. (John Miller was not related to journalist Jay Miller.) There, in a far corner near the fence line, at a barren, unmarked grave Tunnell found using cemetery maps, the group planned to exhume Miller’s remains and extract the DNA. Then, they’d compare those results with samples from the wooden bench Sederwall found in Albuquerque.

This time, the event was kept quiet. There were no public hearings and no front-page headlines. Nor were there efforts to secure a court order. Tunnell says there was no need: Arizona law permitted Pioneers’ Home to authorize the dig, and when he approached cemetery managers with the proposition, he says, they enthusiastically accepted.

The exhumation began that Thursday afternoon, and by nightfall, it was complete. But the controversy was hardly over. When Cooper and a “Billy the Kid junkie from Tucson” named David Snell heard about the exhumation, they both worked the phones, between them contacting the cemetery, local police, county officials, and the attorney general. Their goal? To get the men slapped with criminal grave robbery charges.

The first time Tunnell heard that the authorities were involved, he thought it was a joke. "I started laughing," he says. Tunnell says he’d gone out of his way to make sure everything was done according to Arizona law. When the calls from a detective continued, he says, he lost his patience. "I said, ‘Kiss my ass,’ basically," Tunnell says.

The authorities believed Tunnell’s account — that everyone involved in the exhumation thought they had acted lawfully — and in the end, prosecutors dropped the investigation.

If Cooper had won in Silver City and Fort Sumner, Sederwall and Sullivan evened the score in Arizona. In the most widely published account of the sheriffs’ vindication there, Sederwall boasted of what a DNA analysis from Miller’s grave and the wooden bench would reveal. (He declined to be specific, though, "for fear of provoking attacks from historians.") The pair had even become minor celebrities in France, where a movie that featured them, A Requiem for Billy the Kid, was premiering at the Cannes International Film Festival that spring.

Cooper fumed. In a lengthy complaint against the county attorney that handled the charges, she alleged obstruction of justice. She wrote open records requests to Bill Richardson and then-Arizona Gov. Janet Napolitano seeking confirmation of their meddling in the recent dig. She even contacted the FBI and described what was going on as a vast criminal enterprise operated by public officials.

Her efforts, though, produced little. After hearing about the trip to Cannes, she wrote, “I was miserable. Like a pandemic virus, the Billy the Kid case hoax was about to infect the world."

After Silver City, Fort Sumner, and Arizona, Cooper was now fully committed to a singular cause: revealing what she saw as the sheriffs’ unceasing efforts to topple Bonney’s history. “The hoaxers,” she wrote, “had to be exposed.” So she settled on a new tactic — the open records request, specifically asking for the forensic files from the wooden bench and the grave in Arizona.

Cooper sought guidance from the newspaper publisher Scot Stinnett, who is also one of New Mexico’s leading open records advocates. He recalls Lincoln County telling her they didn’t have any documents. Included with one of the county’s denial letters was a note from Sederwall and Sullivan. Dated Sept. 30, 2006, it described Cooper’s requests as "harassment" and concluded with a vague warning about contacting the U.S. Marshals Service.

Frustrated by the treatment of her records requests, Cooper connected with a lawyer in Albuquerque who eventually sued in 2007. Stinnett became her co-plaintiff. To him, there was no hesitation — it was a straightforward open records case backed by a righteous cause. "Her whole focus was not to let these guys change the history of the state of New Mexico," he says. "That was good enough for me."

At the time, Sederwall and Sullivan were just learning about Cooper, who had only recently shed her anonymity. The sheriffs came to view her as a desperate thief, and her records requests were an "attempt to gain the information we have spent years gathering to add to a book she is attempting to sell," as they put it in a seven-page memo to Rick Virden, the sheriff who replaced Sullivan in 2005.

With the case against them looming, Sederwall and Sullivan resigned their commissions as Lincoln County deputies — a choice, they told Virden in the memo, driven by "political pressure" and "harassment." When they appeared for depositions in August 2008, they presented their defense: The investigation was their “golf game,” a private endeavor they’d paid for. They wouldn’t release any documents, they told Virden, until they felt like it.

It was easy to show that the "golf game" portrayal was recent spin. The men, after all, had spent the last four years running around under the auspices of the sheriff’s office. "They used their status as deputies to get access," Stinnett says. And besides, Virden had sent Cooper the sheriff’s official case file. It was 192 pages, and it contained phone numbers, newspaper articles, and emails, but the most important documents — the forensic examination of the wooden bench and the DNA analysis — were missing.

On Nov. 20, 2009, the judge ordered the remaining files be turned over; if they weren’t, Sederwall, Sullivan, and Virden could face contempt charges. The DNA analysis never materialized, and Virden, who was the legal custodian of those documents, only offered an unsatisfactory explanation: "I’m not even sure (they) exist.”

Lee’s forensic examination of the bench was just as baffling. The sheriffs’ lawyers delivered what they alleged was the original report, but Cooper kept noticing odd details in the documents that led her to think otherwise: One copy, for instance, was missing its "results and conclusion" section. Another one was just nine pages, when Sederwall said in a deposition that it was 12.

Cooper kept demanding an original, and by summer 2012 — nearly three years after the judge’s order — she'd received five different versions of what was supposed to be a single report. "Sederwall had been pulling them like rabbits from a magician’s hat," she wrote.

Was Cooper right? Was Sederwall tampering with official documents and lying about it in court? He responds with a blustery "no" — it was all a misunderstanding. Lee’s report was “cut in half,” he says, because it looked at “two different incidents” — the double homicide and jailbreak in April 1881 and Bonney’s killing a few months later. Sederwall insists he tried complying with Cooper’s requests. "She never would tell me what she wanted," he says. "They were trying to paint me as, I’d made up another report."

Even while Cooper was gathering what she viewed as damning evidence of forgery, perjury, and other possible crimes, her legal strategy was crumbling. By fall 2012, she’d burned through several law firms and attorneys. A couple quit, a couple more were fired; all but one had accepted the case without a retainer, which meant they only got paid when they won or when they settled. Cooper mostly portrayed herself as the victim of fickle, lawyerly maneuvering or political wheeling and dealing. When I ask Stinnett if that's how he viewed it, he says, "Attorneys like to get things over with. They couldn’t see any progress ahead."

In fall 2012, Stinnett and Cooper split over one of these firings. Both forged ahead in the case, though: Cooper represented herself, while Stinnett worked with a firm called Albuquerque Business Law.

It wasn’t long before Stinnett’s lawyers did what the authorities hadn’t in five years: They obtained the DNA analysis. It turned out that the lab that conducted the analysis, Orchid Cellmark, had been bought by a company registered in New Mexico, and when it was served with a subpoena, 133 pages in files were promptly produced. As detailed in the documents, the bones collected from Arizona yielded complete DNA profiles. But the bench samples produced nothing. The results were either inconclusive or they “failed to yield amplifiable DNA,” as the report put it. The bombshell Sederwall alluded to in the aftermath of the Arizona dig — the thing that would “provoke historians” — was nowhere to be seen.

Cooper allowed herself a sliver of satisfaction. "The subpoena was good," she wrote, "because it proved the hoaxing." But to her, the lawsuit was never just about the documents. It was about accountability, about forcing the sheriffs to comply with the law, which meant holding steadfast in court.

So when Stinnett settled with Lincoln County in the summer of 2013 for nearly $200,000 — a sum paid to the trail of current and vanquished attorneys — Cooper was indignant. "As a self-proclaimed open records hero," she wrote, "he bowed out without accomplishing anything.” A settlement, after all, meant no published decision from the judge. It meant he didn’t have to point out who was right and who was wrong.

Cooper refused to settle, and on Dec. 18, she appeared to make her case. This time, there were no lawyers accompanying her. Instead, a camera operator tagged along to capture Cooper’s debut as an attorney.

In the two-hour video that followed, Cooper, with a mop of blonde hair, chunky-heeled boots, and a flowing skirt, methodically detailed her grievances. “This is what it looks like when corruption is out of control — people feel untouchable,” she told the judge. “The only thing to stop these wildly out-of-control defendants is a penalty that won’t be forgotten in Lincoln County.”

On May 15, the judge handed down his decision. It arrived to Cooper inside a thick brown envelope; wary of its contents, she waited a day before opening it. But when she did, she was astonished: The document’s 10 pages offered “complete confirmation of all my accusations,” she wrote. The sheriffs’ conduct — their refusal to turn over records, Sederwall’s altering of public records — was described as “willful, wanton, and in bad faith.”

For the sheriffs’ six years of bad behavior, Cooper was awarded a small fortune — $120,000. It was a victory she described in the most grandiose terms. “May 15, 2014,” she wrote, “is the day I won the Lincoln County War.”

But even in triumph, Cooper saw betrayal and corruption. In her view, she’s suffered maximum public records act violations and is entitled to maximum damages — $100 per day, per violation, a sum, she concludes, totaling just under $1 million.

So last June, Cooper found a “new cause,” as she put it: “protecting New Mexico’s open records law.” In a 41-page document thick with citations and bursting with contempt, she appealed her own victory. The judge had ignored state law, case law, and her civil rights, and he had participated in a "naked ploy,” she wrote, “to free corrupt public officials" from paying for their misdeeds. Her appeal has not yet been decided.

Still, Cooper reveled in winning her bigger battle — exposing what she says is a sprawling, illegal plot to hijack history. “Abuse of power is what the Billy the Kid case was all about,” she wrote.

Sederwall, perhaps not surprisingly, accepts none of this. He roars with laughter when I tell him that Cooper won the case against him — he says he thought she’d settled — and that the judge described him in pretty dismal terms. “I don’t even give a shit,” he says. In his telling, he’s just a guy who wants to know the truth, while scholars like Cooper will stop at nothing to control the history they’re profiting from. “There’s a hierarchy,” he says. "I’m the guy with his hat in his hand looking through the window.”

On this point, Cooper is happy to gloat. “Because of my labors,” she wrote, “New Mexico’s Billy the Kid and Pat Garrett history is, at last, safe from the hoaxers’ destruction.”

But perhaps not for long. Kevin Costner’s National Geographic special — Billy the Kid: New Evidence — premieres Oct. 18. One of the Bonney-philes enlisted to sort through that evidence was Steve Sederwall. He was asked, he tells me, to figure out where the photograph might have been shot. He is credited in the show as “forensics expert.”

Also read:

Want to read more stories like this? Sign up for our Sunday features newsletter, and we'll send you a curated list of great things to read every week!

CORRECTION

A previous version of this story misstated the thickness of the adobe walls in the Lincoln County Courthouse.