UPDATE — Nov. 19, 1:38 a.m. ET: Leon Taylor was executed and pronounced dead at 1:22 a.m. ET.

Taylor, 56, died just minutes after receiving a lethal injection at a prison in Bonne Terre, Missouri, the Associated Press reported. Missouri Attorney General Chris Koster issued a statement after the execution:

MO AG Koster: "imposition of justice ... finally came early this morning" w Leon Taylor's execution.

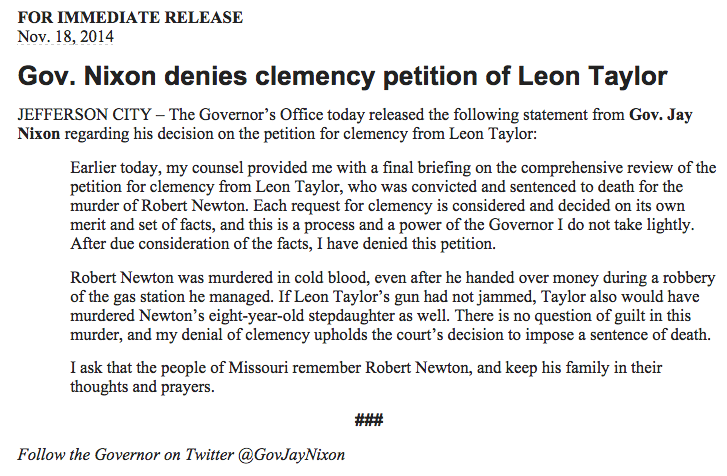

UPDATE — Nov. 18, 11:50 p.m. ET: Gov. Jay Nixon denied Leon Taylor's clemency petition.

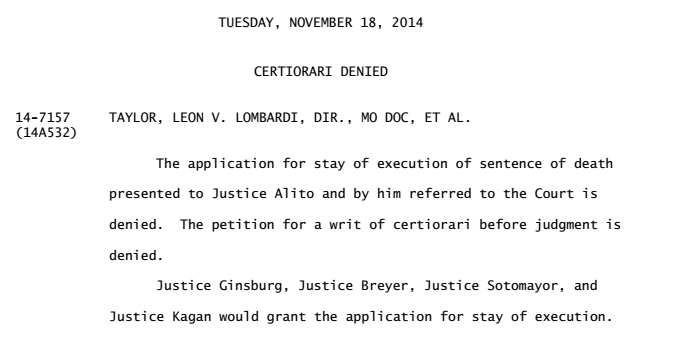

UDPATE — Nov. 18, 9:30 p.m. ET: The U.S. Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito denied Taylor's request for a stay Tuesday night.

Leon Taylor, 56, is scheduled to be put to death by lethal injection at 12:01 a.m. CT Wednesday for fatally shooting Robert Newton, a gas station attendant, during a 1994 gas station robbery in Missouri.

Taylor killed Newton, 53, in front of his 8-year-old stepdaughter, who testified that Taylor tried to kill her too, but his gun jammed.

Taylor's attorneys filed an appeal with the U.S. Supreme Court Tuesday to stop the execution. According to the appeal, Taylor's original mixed-race jury was deadlocked and a judge sentenced him to death. Taylor successfully appealed the sentencing and in a second trial, an all-white jury gave him the death sentence in 1999.

A 2002 Supreme Court ruling stated that only a jury could impose a death sentence. Taylor's lawyers argued that after the Supreme Court decision, Missouri commuted at least 10 death sentences imposed by judges on inmates, except Taylor's.

His attorneys said Taylor is being penalized for successfully appealing his first conviction, the Associated Press reported.

"It is difficult to imagine a more arbitrary denial of the benefit of a state court decision," Elizabeth Carlyle, one of his attorneys, wrote in the Supreme Court appeal.

The appeal also contends that Taylor faced racial discrimination during the second trial. The prosecutor had dismissed six potential African-American jurors, resulting in an all-white jury.

"There are racial concerns throughout this case," Carlyle told Reuters. "He was an African-American man accused of killing a white man."

His lawyers also argue that the execution should be delayed because of ongoing litigation involving Taylor and other Missouri death row inmates. The inmates have filed a lawsuit against the state over its secrecy laws on lethal injection drugs.

Gov. Jay Nixon is also considering a clemency petition filed by Taylor's attorneys.

In 1994, Taylor shot and killed Newton during a gas station robbery. He turned the gun on Newton's 8-year-old stepdaughter but it jammed.

Taylor planned to rob the gas station along with his half brother and half sister. At gunpoint, he forced Newton to put $400 in a bag, which his brother took to the car. Taylor took Newton and his stepdaughter to a room. Despite pleading with Taylor not to kill him in front of the child, Taylor shot Newton in the head. He then turned the gun on the little girl, but it jammed, so he locked her in the room and left.

The girl was the prosecution's primary witness for the trial. During Taylor's sentencing, she said that when her stepfather was killed, "the best thing in my life was destroyed," the Kansas City Star reported. "It's lonely out there with no dad. I've never had so many nightmares. I'm so unhappy."

In his clemency petition, Taylor's lawyers say that he had an abusive childhood and struggled with alcohol and drug addiction.

According to his previous petitions, Leon Taylor's mother was a chronic alcoholic who gave him alcohol when he was 5 years old. Her children witnessed her stabbing and shooting her boyfriends and killing her husband, the Columbia Tribune reported. She also choked and beat her children and focused much of her abuse on Leon, who was the oldest. He was also reportedly sexually abused as a 5-year-old.

His lawyers say that despite his troubled past, Taylor has reformed in prison and is

a positive influence on other inmates.

Taylor would be the ninth person to be executed in Missouri this year. Another inmate is scheduled to die in December, making it the highest number of executions in the state since 1976.