NAIROBI — Women in Sudan are using private Facebook groups created to creep on crushes to dox state security officers brutalizing demonstrators during huge anti-government protests sweeping the country.

When security agents and police abusing their power have had their identities exposed, they have been hounded by people in their own neighborhoods, beaten up, and sometimes even chased out of town.

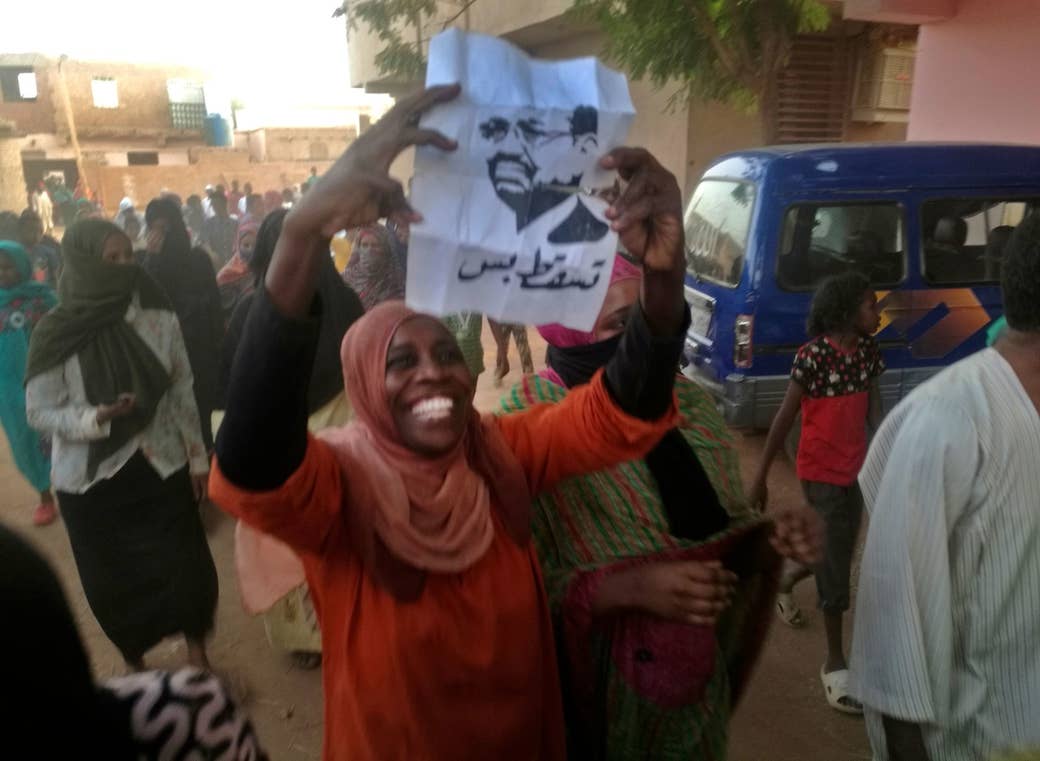

The groups — only accessible via a virtual private network (VPN) after the government blocked social media — are part of the response to a brutal crackdown on anti-government protests that have swept the country since December. They are the largest ever against the regime of Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir, who took office in 1989 and whom protesters accuse of enforcing oppressive laws and wrecking the economy. At least 57 people have been killed in the protests, and countless others have been shot at, teargassed, had their hair cut off by officers, and tortured.

Sudan’s morality laws prevent women from gathering in public; dictate the clothes they wear; and authorize the use of corporal punishment, like lashing and stoning, if they violate or criticize the rules. As a result, private Facebook groups have become a popular way for millions of Sudanese women to safely communicate with one another.

Now, there are dozens of groups on the platform with tens, and sometimes hundreds, of thousands of members. Although the groups are well-known among Sudanese people, they are rarely discussed outside of the community.

The Facebook groups are exclusive to Sudanese women, and were set up long before the protests began. Conversations within them used to be dominated by inquiries about men the members were romantically interested in. But since December the focus has shifted to outing members of Sudan’s National Intelligence Security Service, police, and plainclothes officers who have been abusing protesters.

Bashir has said protesters cannot change the government with Facebook or WhatsApp. But the women behind the doxing campaigns may yet prove him wrong.

The Facebook groups have come to be known by Sudanese people — inside the country and throughout the diaspora — as the unofficial intelligence apparatus of Sudan, and have earned such notoriety that security agents have started hiding their faces in public for fear of appearing in one of the groups.

“No one ever thought that we could make change as women, but we are more powerful than any government,” Enas Suliman, a 26-year-old teacher who has been protesting since December, told BuzzFeed News on the phone from Bahri, a neighborhood in the capital, Khartoum.

“People who used to run [from the security forces] don’t run anymore. That’s very confident. They can’t shut us down.”

Sudan’s protests began when the government tripled the price of a loaf of bread and ATMs ran out of cash, and the protests have since morphed into a nationwide movement calling for the resignation of Bashir, who has been indicted by the International Criminal Court for war crimes, genocide, and crimes against humanity.

The mass demonstrations have taken place in 15 of 18 states across Sudan and included people of all ages. State security forces responded with what human rights organizations have called excessive force, firing live and rubber bullets into the crowds, beating activists in the streets, and making sweeping arrests, including of journalists and doctors. On Dec. 20, the government cut off access to social media platforms like Facebook, WhatsApp, and Twitter — people have been relying on the use of VPNs ever since.

“No one ever thought that we could make change as women, but we are more powerful than any government.”

But in recent weeks, the situation facing Sudanese protesters has grown significantly worse, according to the Sudan Doctors' Syndicate, the country’s doctors union.

Tear gas is “being used excessively and without any due reason in residential areas, fired inside houses with total disregard to inhabitants, many of whom were children and elderly,” the organization said in a statement. It also noted that tear gas was being fired “as a potentially deadly missile directly at protesters’ bodies” instead of live bullets, and pointed out a spike in instances of security forces running over protesters with their vehicles.

But activists and human rights advocates have told BuzzFeed News that despite the increasing violence demonstrators face, the protests have too much momentum to slow down, especially now that so many women are at the helm.

“If you’re a woman in Sudan who’s decided to take political action, you’ve already fought against so many authorities,” Muzan Alnail, an engineer and protester, told BuzzFeed News by phone from Khartoum. “And once you’ve made that decision, security forces won’t scare you.”

Before the protests started, the main purpose of the Facebook groups now being used to dox security forces was for Sudanese women to gossip about their crushes.

“They will upload a picture of a boyfriend, coworker, a guy who wants to marry them, a guy they saw at a party, or a guy who they saw around, whatever, and ask other girls [for] information about this guy,” Miada Akasha, a teacher, told BuzzFeed News in a WhatsApp message from Saudi Arabia, where she now lives. Though she’s no longer in Sudan, she still has a lot of relatives there, many of whom are activists, and follows the protests on social media.

“And boy, did the other girls deliver! They would provide full names, addresses, family members, ex-girlfriends, and sometimes even [the names of] wives and children!” Akasha added.

The groups were well-known throughout the country for years, and men were vocal about their disdain of them, said Akasha, 29. She figured it was because they were experiencing, perhaps for the first time, what it felt like to be objectified on social media.

“All of a sudden, people realized: ‘We can use this.’”

The chatter from the groups slowed down for most of 2018, but according to Suliman, the elementary school teacher who has been protesting since December, the violent response by security forces sent many angry Sudanese people to social media with photos they’d taken of the officers, asking for information on them.

“Once, a woman responded to a man who shared a photo of a national security agent, saying that she would share it with her group,” Suliman told BuzzFeed News.

“Within five minutes, we had information on him: his mother’s name, if he’s married or not. Some of his ex-girlfriends were in the group and talked about him.”

That was the moment that things began to shift in the group, she recalled. “All of a sudden, people realized: ‘We can use this.’”

Male protesters, who aren’t allowed in the Facebook groups, began sending women more photos on Facebook and WhatsApp of the alleged perpetrators from the national security forces. And the women — who were by then accustomed to digging into people’s lives online for personal reasons — turned up line after line of detailed information about them, down to the color of their front door. People who work for the government in Sudan usually hide the fact they do from their friends and families, making their exposure that much more of an affront to their authority.

On Jan. 17, Nadreen was protesting in Khartoum when she was arrested and jailed for three days. (The 28-year-old doctor asked that her last name not be used out of concern for her safety.) She told BuzzFeed News on the phone from the capital that one of the security agents, a woman, was cruel and aggressive toward her and the other women who had been detained.

The woman security agent made her drink vinegar, Nadreen said, and beat all of the detained women protesters viciously.

Nadreen didn’t expect to see the woman again, but a week after she was released from custody, she came across the woman’s photo in one of the Facebook groups, along with her full name; the university she attended, the year she graduated, the subject she studied; the make, model, and license plate number of her car, which reportedly has “lightly tinted windows”; and the address of her home, which has a turquoise door.

“Expose all the informants and give them a real beating so she knows not to touch honorable revolutionary women,” one group member wrote of the woman officer.

“They knew they’d be named and shamed in their neighborhoods and families.”

When security agents’ information has been publicized, people have taken action. One video seen by BuzzFeed News shows demonstrators surrounding an officer’s home, calling him a weasel — a phrase considered much more offensive in Arabic than English — over and over again, until he eventually drove off.

In several screenshots of conversations from the groups shared with BuzzFeed News, women repeatedly encourage one another to “not go easy” on the informants when it came to exposing their personal information. They address other group members both as “lovelies” and “revolutionaries.” And every once in a while, the group members come across faces they know personally.

Suliman, the teacher, once scrolled past a photo of a man who was beating protesters with a stick. After the details about him surfaced in the group, she realized that she went to college with him. She would have never guessed that he would have sided with the government.

“He was always walking around campus talking to people,” she remembered. “He didn’t use to be so evil.”

The vigilante Facebook groups have gained so much notoriety, and the danger they pose to security officers is so real, that officers have resorted to covering their faces in public.

Alnail, the engineer, has been participating in the demonstrations since December, when the Sudanese Professionals Association began calling for Bashir’s removal. She told BuzzFeed News over the phone from Khartoum that when she was beaten, arrested, and detained last month, she noticed that the guards in her holding facility went out of their way to hide their faces, and yelled at the women not to look at them.

“They didn’t want to end up in the Facebook groups,” said Alnail, 32. “They knew they’d be named and shamed in their neighborhoods and families.”

Nadreen, the doctor, said national security officers have started obscuring their faces even while patrolling the streets, and said that the sight of them doing that makes women “feel more feared.”

In January, Bashir referred to protesters as “rats,” saying that he would only cede power to another military official (he serves as a field marshal in the army). But in an address to the nation on Feb. 7, he appeared to soften his stance against the demonstrators. He acknowledged that certain factors, like inflation and unemployment, had led young activists to the streets. He also promised to release journalists who had been jailed.

But as the protest movement in Sudan continues to grow, in part due to the women’s Facebook groups, human rights advocates are worried that the government will crack down even harder on them.

Ahmed Elzobier, an Amnesty International researcher for Sudan, told BuzzFeed News that he got reports this week of officers demonstrating increased hostility and sexual violence toward women, which could be a response to the doxing.

“They were already instructed to intimidate them with verbal abuse, calling them prostitutes, whores, and saying that they’re only protesting because they want sex with boys,” Elzobier said.

“The military and police would get away with so much, and no one would know anything about them. Fangirls came to the rescue.”

“Now we’re seeing something different. They’re being touched inappropriately, and threatened with rape.”

But the activists continue to appear undeterred, online and off.

Nadreen, the doctor, showed BuzzFeed News screenshots of a conversation within one of the groups where the relative of a security forces agent identified herself after his photo was shared.

“I am his sister,” she wrote. “What do you need?”

When others in the group sympathized with her at discovering that her brother was an informant for the government, the woman dismissed their concerns, saying that her brother was basically dead to her for siding with Bashir’s regime, and insisted that she help them expose him.

And the protests themselves show no signs of stopping. The last major demonstration took place in in Omdurman, the second-largest city in the country, and was specifically in honor of women.

According to Suliman, who was at that protest, demonstrators marched toward an all-women prison, with women in the front and men trailing behind them. She said the men called the women protesters "queens," and thanked them for their efforts in the movement, acknowledging the huge role they have played. As has been the case in so many protests before, the demonstrators clashed with security forces, throwing stones at the officers and receiving tear gas in return.

It doesn’t seem as though the violence against activists will stop either, but the exposure and accountability that the security forces now face as a result of Sudanese women’s Facebook groups still feels vindicating for them.

“The military and police would get away with so much, and no one would know anything about them,” Akasha, the teacher, said. “Fangirls came to the rescue.”●