Controversial plans to build a Muslim community center and mosque in New Jersey were delayed again by local officials after a nearly five-hour meeting on Monday night — amid renewed claims the that intense scrutiny of the project is the result of anti-Islam sentiment.

It has been more than a year since the first tense zoning board meeting in Bayonne, where residents for and against the mosque clashed. At the time, anti-mosque protesters held signs that read “If the Mosque Comes the Mayor Go’s,” while others just read “Trump.” Counter-protesters held “No to RACISM” and “Anti-Muslim Bigotry” signs. After that meeting there was a series of delays — a lawyer for the mosque got sick, and the town asked for more traffic studies, among other things — leading up to Monday night's second session.

During a ten-minute break on Monday evening, a member of the audience using a crowded bathroom loudly asked, "Does anybody want a pork-chop?" and called muslims “hajis.”

“Ain’t no one taking my Bayonne,” he added.

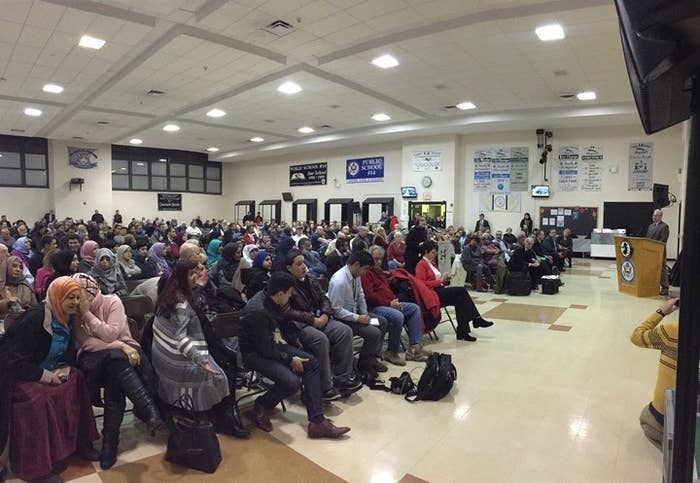

In anticipation of a large crowds on Monday, Bayonne officials held the meeting in the auditorium of a local school instead of city hall. Inside, people held signs that read “Muslim Lives Matter” and “No to Muslim bigotry.”

For more than four hours, the zoning board listened to comments from the public directed towards experts who were hired to revise plans for the mosque.

One after another, Bayonne residents, at times audibly agitated, asked an engineering expert who would be monitoring how many people would be at the mosque at any given time, how close the mosque is to a flood zone, and the location and height of curbs in a city where signs reading “Save Bayonne” and “Stop the Mosque” have been popping up.

The board’s chairman repeatedly told the audience to refrain from outbursts, and corrected speakers when they deviated from asking questions to state their opinion on the proposal.

Mosque opponent Joseph Wisniewski in a heated moment at the meeting

No less than three police officers were present at all times. Nearly every chair was filled, about equally divided between people for and against the mosque.

“In all your experience doing this type of work,” one of the audience members who appeared to be for the mosque asked an engineering expert, “does the traffic impact here seem to be a significant issue compared to other buildings you’ve surveyed?”

“No, not an issue at all. In fact, it’s been one of the survey’s with the least traffic issues,” the expert replied.

Audience members against the mosque, one after the other, grilled the engineers hired by Muslims for Bayonne to conduct studies on the proposed building site and traffic impact for the zoning board.

“Do you live in Bayonne?” Joseph Wisniewski, 51, asked the traffic engineer, as the meeting dragged into it’s fourth hour.

“No, but mother used to,” the engineer replied.

“I don’t care about your mother, that’s another story!,” Wisniewski shouted, pounding his hand on the podium. The crowd erupted.

Moments later when the board’s chairman told Wisniewski he had to sit down if he had another outburst, he looked back and shouted, “And stop it!,” while pointing his finger to the side of the auditorium that contained most of the Muslim Americans in attendance.

As the meeting almost entered its fifth hour, the lawyer for Bayonne Muslims, the nonprofit behind the proposed community center, said he had one more expert witness to call. But that was one too many. The zoning board chairman said "I don't take witnesses after 10 p.m."

And with that he ended the discussion of the proposed mosque. No vote was taken.

Standing in the auditorium after most of the crowds left, the mosques spokesperson, Waheed Akbar, said, "We'll just have to wait. We have patience."

Wisniewski, 51, lives a block from the proposed mosque and said his opposition to the mosque has nothing to do with Islam or having Muslims in the area. Instead, he says he’s concerned with soil contamination, increased traffic, and how the center will affect the residential neighborhood.

“Does a mosque belong on a dead end block in a residential neighborhood? It's only a story because they’re pushing their way into a quiet residential community,” Wisniewski said, adding that he has been labeled a racist for opposing the mosque.

The Muslim community center would be on a dead end street at the site of an abandoned warehouse. Amid public objections earlier this month, Bayonne’s zoning board approved a 106-unit, six-story apartment building on the same street from the proposed mosque.

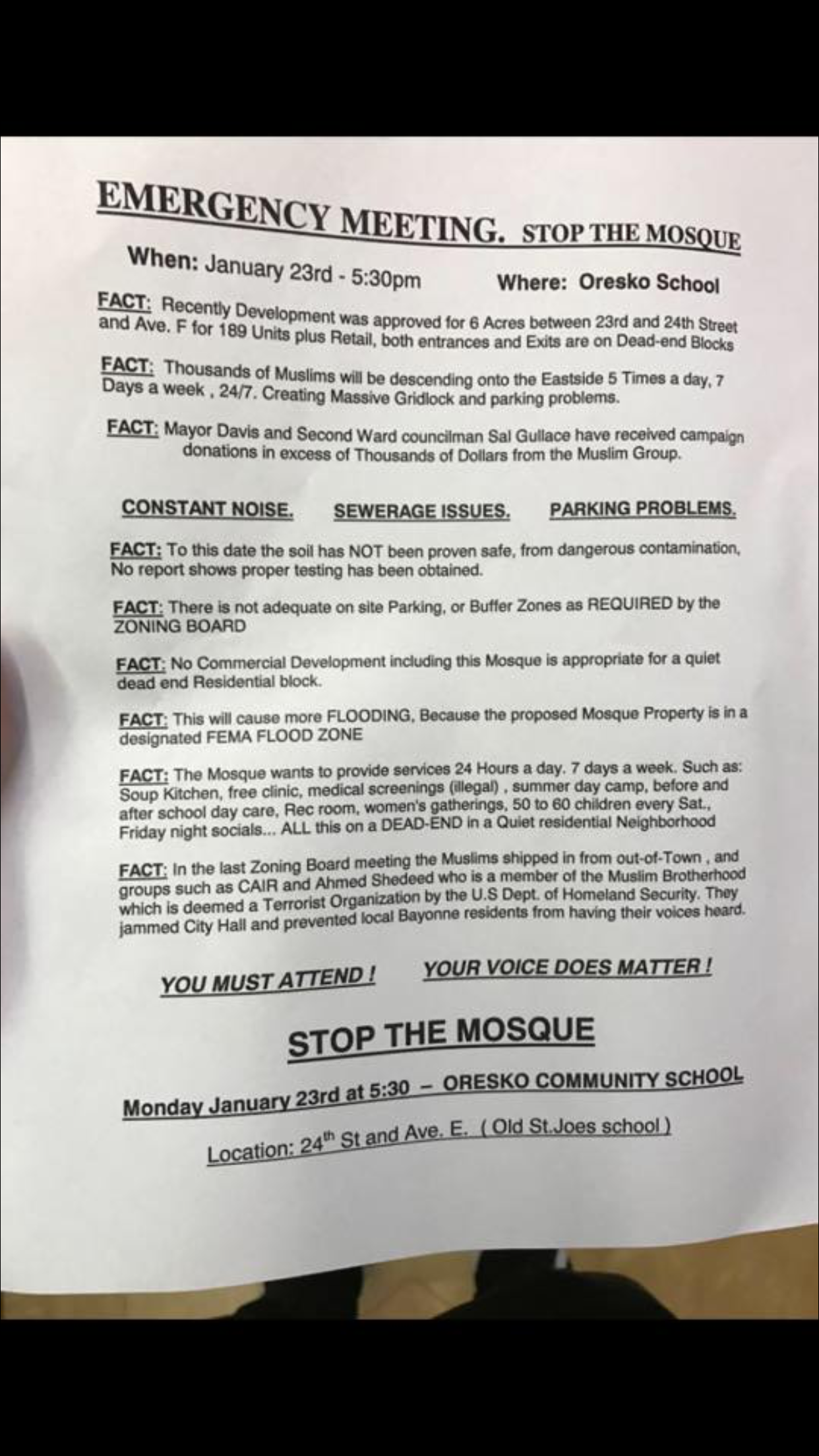

Before Monday’s meeting, a group opposed to the mosque distributed a flyer that falsely claimed that “Muslims [were] shipped in from out-of-town” and that that a Muslim civil liberties group “jammed City Hall” and “prevented local Bayonne residents from speaking.”

But many Muslim Americans, especially those in Bayonne, believe the staunch, and at times angry opposition to mosques, stems from anti-Islam sentiment. They and civil liberty organizations also believe local zoning regulations and land-use objections to mosques, Muslim cemeteries, and community centers are nothing more than legalized forms of bigotry.

Akbar told BuzzFeed News that while some concerns are valid, opposition from people on the other side of town, in addition to statements made at the last meeting, such as if Muslim residents believe in Sharia law, has led him to believe bias against Muslims is a factor.

“Sure, the traffic and parking can be a concern, but if everybody's concern is also about terrorism and the religion, you begin to wonder what is really driving people’s opposition,” Akbar said. “What else does a sign calling for saving Bayonne mean from a resident in a part of town where the mosque won’t be?”

Around the country, meetings for similar proposals can also get heated, as a video of a meeting in Spotsylvania, Virginia, in 2015 shows.

“Every Muslim is a terrorist, period. Shut your mouth!” a man said to Samer Shalaby, an engineer who was presenting plans for a mosque to the community. “Nobody wants your evil cult in this town.”

“People hide their racism behind these zoning issues,” said Abdul Mubarak-Rowe, communications director for the New Jersey chapter of the Council on American-Islamic Relations. “They have been hiding their bigotry behind zoning issues that have been addressed in previous meetings.”

Each Friday for the last eight years, 180 Muslim Americans in Bayonne pray in the cramped basement of St. Henry’s School, as BuzzFeed News reported last year. Underground, they hold prayers, talk, have meals, and break their fast in the month of Ramadan. The basement can’t fit everyone for Friday prayers each week, so two separate services are held.

The community center proposal has resulted in numerous alleged incidents of vandalism and intimidation. The basement-turned-mosque space was vandalized last October with “Fuck Muslims” and “Donald Trump” graffitied on the walls. A 20-year-old man was caught and eventually pleaded guilty to criminal mischief for the crime.

Conversely, a woman alleged that she was threatened at her home last year for displaying the “Stop the Mosque” and “Save Bayonne” signs.

Zoning issues vary from town to town, but reasons cited for rejecting or stalling projects have ranged from concerns about traffic congestion and parking issues, to not being “harmonious” with “existing buildings.”

But rejection of Muslim community centers and cemeteries have not gone unnoticed by the Justice Department.

Just 30 miles away in Bernard Township, New Jersey, the Islamic Society of Basking Ridge’s proposal to build a mosque was denied by the zoning board after over four years and 39 meetings. The Islamic Society of Basking Ridge decided to sue the town in March 2016, alleging officials had violated their freedom to practice religion. Months later, the Justice Department filed its own lawsuit, alleging Bernard township violated the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act of 2000 (RLUIPA). Township officials “kept moving the goalposts by using ever-changing local requirements to effectively deny this religious community the same access as other faiths,” US Attorney Paul Fishman said in a statement.

According to a pre-motion letter to the judge, emails between township officials contained anti-Islam sentiments, including one that stated Muslims “are allowed to lie for the sake of their religion."