My grandmother was one of the beige ladies of Santa Barbara, a rare and particular breed of self-made California woman with scotch in her liquor cabinet, Didion and Butler on her bookshelf, and a mottled spectrum of cream, ecru, and taupe in her closet. She had pursued this life with exceptional passion and focus, a single mother who grew up a young Okie picking tomatoes in the Central Valley, then moved back to Georgia to put herself through graduate school. She came back to California seemingly reinvented: No longer the sickly little barefoot girl, but the shrewd investor with a new wardrobe of linens and silks.

We see these women, daughters of privilege, and we think we know who they are. But I didn’t know my grandmother until after she had died, until I found myself sitting with her things stacked tall in boxes, things I had no idea what to do with.

So I have spent the better part of 15 years with these things. And during that time, nearly everything about how we value and exchange old things has changed.

My grandmother was the only one in my small family who invested much money in her appearance, but she seemed always disappointed in mine. When I was 8 she grabbed my round belly with her thin, braceleted hand, and warned me not to get too fat. When I was 10 I snagged a pair of her old Reebok sneakers and wore them to school every day for a week, until I could no longer justify the discomfort of wearing shoes two sizes too big. When I was 12, she bought me my only brand–name piece of clothing, an OP T-shirt from a sales rack at Macy’s. I wore it threadbare, until the heather gray poly-cotton pilled and the seams split.

She was, as it were, a rather cool cucumber, and I admired this deeply, even though I didn’t quite understand the contours of her beliefs. She complained that the quality of department store goods had deteriorated, but also cringed at every price tag. When her home and everything she owned burned to the ground in a wild canyon fire in 1977, she took the loss in stride, rebuilding promptly and without question in the very same spot, but later, she was not terribly pleased when she found out I’d taken those Reeboks.

A psychologist and shrewd investor who’d made a bundle in real estate and on the stock market, she painstakingly planned her estate down to every dollar. And so it seemed strange when, on her death bed, about to succumb to a cancer she’d been fighting for years, she told us not to give any of her things away. “Sell everything,” she told my father. Despite her wealth, she couldn’t fathom the idea of getting no return on all her small investments.

Now, 15 years later, her old home looks much like it did when she died. Instead of entrusting her things to an estate sale dealer, my family moved in to the house and continues to manage each item individually — each silk slip, each cancer wig, each hand-carved trunk from China. Which is to say, they hardly manage them at all.

And so in the middle of this process, it was decided that I would be responsible for the clothes. My father hoped that I might like to keep most of them — despite my grandmother’s fears of my eventual weight gain, our waistlines were the same. But if this was supposed to feel like a windfall, well, it didn’t. My parents delivered the boxes to my home some 350 miles away, and here they have sat for the past eight years.

Before industrialization, hand-sewn clothing held its value in the secondhand market. Today we tend to like our things, from our blouses to our phones, to be as new as possible. We value newness so much that fast-fashion houses are churning out new styles not every season, but every day. Our clothes have a planned obsolescence, and what we spend on them is sunk cost. The most you might expect to recover on a contemporary near-mint-condition garment is maybe 20% what you spent — unless you plan to hold on to it for decades, and unless it falls apart before then.

With the growth of fast fashion and increasingly cheaper manufacturing, two secondary markets emerged: for charity and for style. Vintage clothing is one of the few if only slivers of the fashion market that actually appreciates with time, as the demand for what is by its nature a limited and constantly shrinking resource has only grown since the 1990s, a principled and stylistic response to a destructive if shiny global clothing supply chain.

But as I was shoving the eighth dusty plastic bin into my closet in 2007, this market was in a state of upheaval. Where brick and mortar vintage stores once appealed to local markets, the internet has now created one global and highly competitive one. At the same time, demand has only increased as new interest in eco-friendly goods has spurred more conscious customers to shop thrift and vintage. Now they can find them from eBay to Etsy, Instagram to Poshmark.

Compared to traditional fashion, the vintage clothing supply chain is bizarre. Dealing in high quantities is not conducive to picking and choosing, and for many vintage sellers, collections like my grandmother’s are their bread and butter. When I began to write this story, a friend warned me: Don’t tell anyone what you have, unless you’re ready to part with it now.

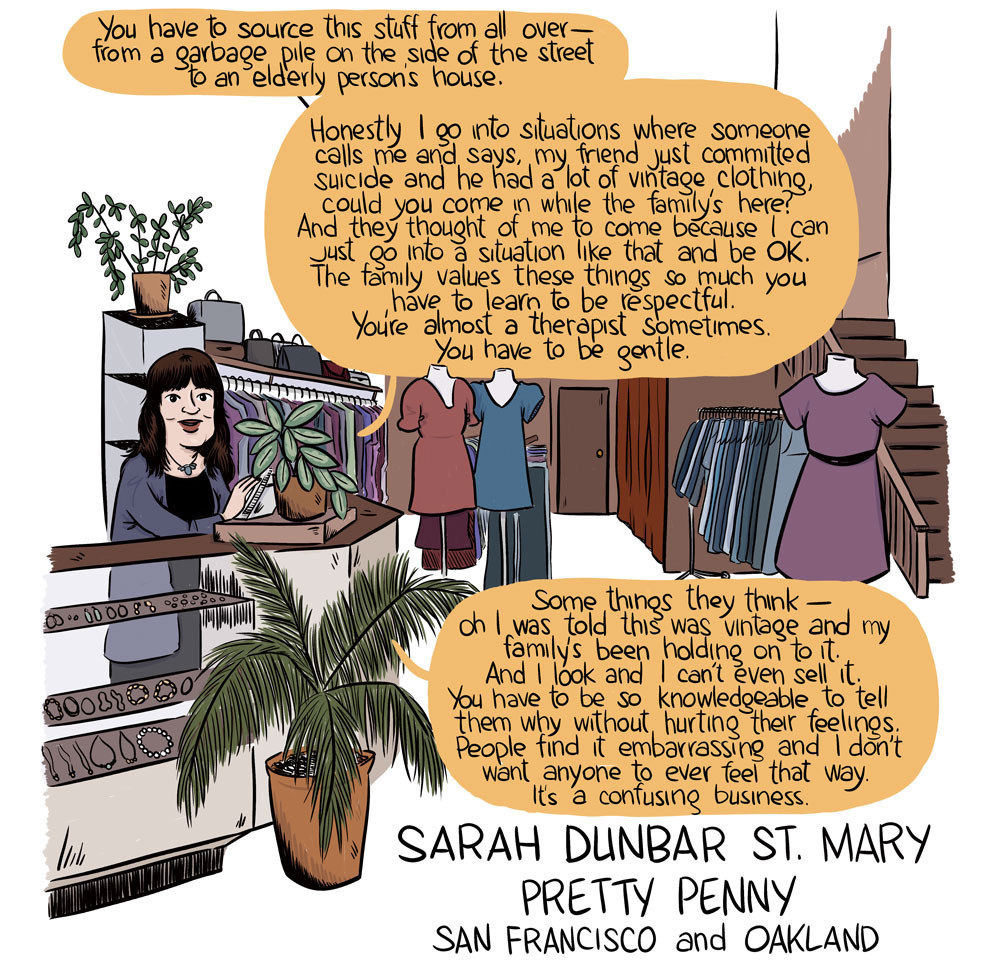

But vintage value is still a nebulous force: What might sell for $500 on Etsy would only fetch $100 in a store. And the dealing is still subjective — each purveyor is a kind of curator. “Something could be vintage Chanel and it could be the ugliest thing I’ve ever seen and I’ll pass on it,” says Sarah Dunbar St. Mary, the owner of the vintage store Pretty Penny. “I perceive value differently.”

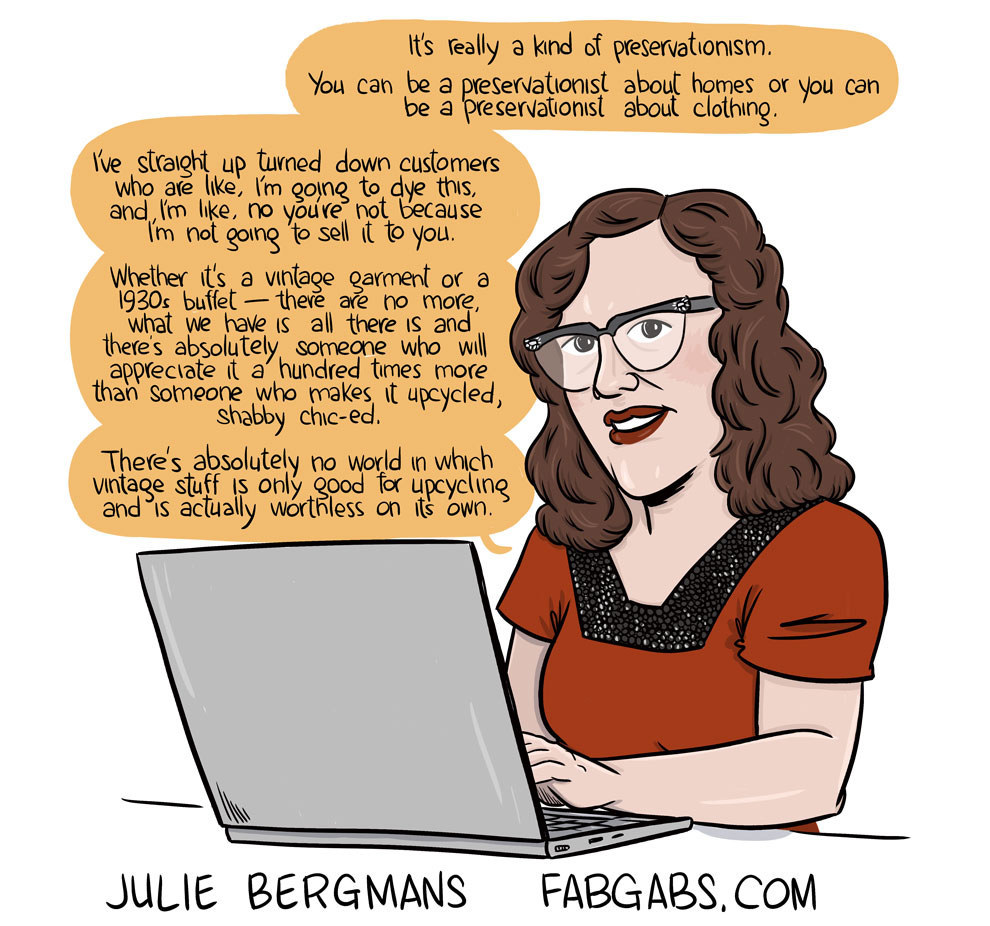

And vintage is not immune to the economic trend bubbles that run the fast-fashion market — trends come and go. Still more vintage dealers buy old to make new, “upcycling” their findings — a practice that doesn’t sit well with hardcore vintage sellers.

A booming vintage market now has its own fast-fashion shadow. While they have faced lawsuits for copying designer looks, fast-fashion houses constantly look to vintage for inspiration. Designers for companies from Forever 21 to Michael Kors frequent St. Mary’s shops, buying old pieces to reproduce new for customers unable or unwilling to spend a premium on vintage. Because no matter how popular vintage clothing might become, most of us still value immediacy over history — except when it’s our own.

I don’t tell Julie Bergmans, who runs the Etsy shop FabGabs, or St. Mary about my grandmother’s clothes.

I look at the stacks of my grandmother's clothes overwhelmed, bewildered. This is not a windfall of Chanel suits and Ferragamo shoes. The fabrics seem nice, but what do I know about fabrics? It doesn't feel like hoarding, but denial. I silently agree with my grandmother: These things do have value, or they seem to, or they do to me.

I can only imagine the kind of collection she had in 1977, a collection that burned along with her house. But in this market, where “vintage” is subjective, older is not necessarily better. I toy with the idea of opening an Etsy shop and unloading my grandmother’s collection piece by piece — until I look at Etsy shops like Bergmans’, full of professionally photographed models and painstaking item descriptions. I do research a few of the pieces with labels I recognize, mostly department store brands in embroidered script. The items in my dusty bins with the greatest resale value turn out to be the most unassuming, neutrals in boxy shapes made only a few decades ago, just in time to come back in style. The long black cotton-silk blend vest that wears like a soft flour sack is apparently a top prize: I find a ringer listed for $108.

I say that my reluctance to part with these boxes is due to the complexity of this market, the demands of independent research, or my unwillingness to be embarrassed by a discerning dealer. But after eight years, it’s clear there’s something else happening here too. I held on to these boxes through my leanest years. Even when I most needed the money, I never tried to sell one piece — because what if I couldn’t? Or, maybe worse, what if I could?

There are over 200 items here, each from a different era, and each seemingly owned by a different woman. By the time I knew her, she was all camel-colored natural fabric blends, but there was a time when my grandmother was burgundy business pencil skirts, gauzy quilted pants, wild and transparent prints. She held on to these things to remind herself, it seems, of that time, too — a time when she was not, as it were, quite such a cool cucumber. And I don’t know how to part with it. I can’t bring myself to wear it outside the house, but who else could appreciate this red embroidered vest with the pockets made to look like gape-mouthed frogs as much as I do? Who would know what it means?

These things are the last vestiges of a woman who I never really knew in life, and who I keep trying to learn in death. But I do spend the time to glean the things I truly want — the first edition of the White Album, the billowy black silk tops, the hand-carved figurines from her solo travels around the world. Whenever I discover a shared interest or similarity, I mourn a bit anew for this person, still a kind of stranger.

Want to read more essays from Inheritance Week? Sarah Hagi wrote about paying remittance. David Dobbs explained the genetic research industry’s exaggerated picture of genetic power. Syreeta McFadden reflected on what it’s like being brown in a world of white beauty. Sharon H. Chang wrote about society’s fixation with mixed-race beauty. Chelsea Fagan compiled lessons on love and money from our parents. AJ Jacobs wrote about planning the world’s largest family reunion. And finally, Rosecrans Baldwin wrote about reciting poetry at public gatherings, something he inherited from his grandfather.