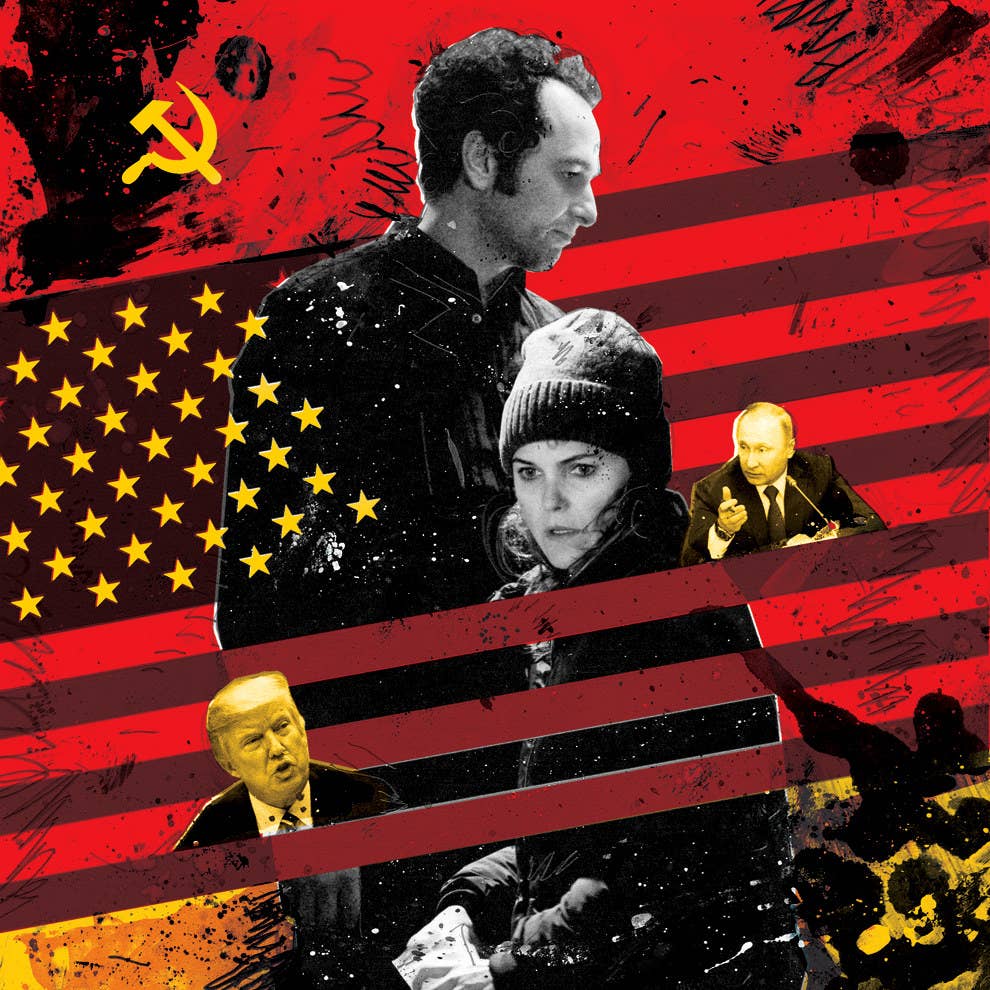

Last summer, as the love affair between Putin and Trump was growing and the 2016 election was just starting to descend into chaos, I began binge-watching FX’s The Americans, which tells the story of 1980s KGB spies (“illegals”) posing as suburban Virginia couple Philip and Elizabeth Jennings (Matthew Rhys and Keri Russell).

Though the DNC had already been hacked, Clinton campaign chairman John Podesta’s emails, which the US intel community assert were stolen by Russian hackers, had not yet been released by WikiLeaks. Trump hadn’t yet called on Russia to hack Clinton’s own emails. A diplomat hadn’t yet been found dead in mysterious circumstances at Russia’s consulate on Election Day. BuzzFeed News hadn’t yet published a widely circulated but unverified dossier alleging the Russians had ample material to blackmail Trump, introducing the term kompromat to the American public. Michael Flynn, Trump’s national security adviser, hadn’t yet been forced to resign after misleading the vice president about discussing sanctions with the Russian ambassador. And Attorney General Jeff Sessions hadn’t yet recused himself from investigations into Russian interference in the election.

For the last few months, the news has played out like a spy thriller. As more than a few people have pointed out on Twitter, we’re basically living in an episode of The Americans now.

a gripping serial about Russian operatives working to undermine American democracy. But once you’re done with the news, watch #TheAmericans

While showrunners Joe Weisberg and Joel Fields aren’t entirely comfortable with their show’s proximity to current events, one of the show’s draws has always been its basis in reality: In 2010, the FBI busted a ring of underground Russian spies, including one couple who told their two children they were Canadian. East German Stasi agents actually did seduce and marry women who worked in West German offices to get information, like The Americans’ Philip Jennings does with FBI secretary Martha Hanson (Alison Wright) in the first season. One of the key ideas underpinning the show, as Fields said on a conference call with reporters last week, was that “this conflict was a relic of a bygone era, and so we could look at it with fresh eyes, and that could trigger us to think about why we have enemies, why we become enemies, why human beings always seem to return to this tribal ‘us versus them’ stance. We certainly could not have predicted that the very same nations would be facing off again.”

For those of us who didn’t really experience the Cold War or know much about it, the show provides arguably the most nuanced window ever crafted for film or television into the era that shaped our parents’ generation. Distance from the emotional and political divides of the past has meant that until recently, The Americans, like its beloved mail robot, felt like a fun retro throwback.

“The initial idea of the show was really to say, ‘Hey look, these people who we think of as enemies are really just like us,’” Fields said at a Television Critics Association event this past January. That's because it’s a lot easier to "root for the KGB," as the showrunners put it, when you know who’s going to win in the end. But now, things between Russia and the US are frostier than they’ve been in decades, and distrust between Republicans and Democrats runs deeper than at any other point in recent memory. A show that’s made “humanizing the enemy” its job feels newly urgent in more ways than one.

Since it began, The Americans has been a critical darling with a passionate fan following. It has been nominated for Emmys but failed to clean up beyond Margo Martindale’s two Emmy wins for Outstanding Guest Actress in a Drama Series. Russia’s resurgence as a US adversary — remember when Barack Obama quipped to Mitt Romney in 2012 that “the 1980s are calling to ask for their foreign policy back”? — seems likely to propel the show from underdog to serious awards contender and boost ratings, which fell from 6.1 million average total viewers to 3.4 million from the first to fourth seasons. But ardent Americans fans know the show has always excelled at drawing a complex picture of a time and place that’s usually flattened.

Parents and children always inhabit different worlds; on The Americans, those differences are just a lot more intense.

The Russian characters — apart from Philip, Elizabeth and their fellow "illegals," who are required to speak only English while in the US — are played by Russian actors, and the dialogue is translated by well-known Russian-American writer Masha Gessen. The show is delightfully dedicated to period detail, from the KGB cameras lent by spy researchers to what the Jennings kids are watching on TV and the release dates of songs on the soundtrack. But rather than simply construct a historically accurate ’80s museum where things sit still, The Americans fills that space with energy and complicates it. No one on the show is a monster, even when they do monstrous things.

By the end of Season 4, undercover agents Philip and Elizabeth Jennings had revealed their true identities to their teenage daughter Paige (Holly Taylor) and were considering moving the family back to Russia after the capture of a fellow "illegal" living in the United States under a false identity. The couple wrestled with the psychological toll of two decades of killing for the KGB, while Paige was weighed down by the knowledge that as an American high schooler in the height of the Cold War, her parents were agents of the Evil Empire. Her younger brother, Henry (Keidrich Sellati), has been in the dark so far, but the showrunners have teased that he’ll get more of a storyline in Season 5.

Philip and Elizabeth are very different as parents. He easily cracks jokes over breakfast, while her idea of mother-daughter bonding is to pierce Paige’s ears with a needle and an ice cube in the middle of the night. But everyone can relate to Paige starting to see her mom and dad as individuals, and the pain Philip and Elizabeth feel watching her grow apart from them the way all kids inevitably do. That the Jennings parents and children have grown up in such drastically different circumstances only raises the stakes of the generational divides felt in many families. Elizabeth telling Paige she doesn’t know how easy she has it reminds me of the awareness I had of my father’s childhood in wartime in the north of England, where rationing remained in place until he was well into his teens. Parents and children always inhabit different worlds; on The Americans, those differences are just a lot more intense.

That we see Elizabeth and Philip as parents, Oleg Burov (Costa Ronin) as a son, and Nina Krilova (Annet Mahendru) as an estranged wife who wanted more from the world than her marriage could offer makes these characters knowable, if not necessarily forgivable.

“We thought of people in the KGB as bloodthirsty and terrible and evil in many ways, but once we thought and learned more about individual KGB officers after the Soviet Union fell, the picture didn’t match up in a lot of ways,” Weisberg said. “So we started painting this portrait of these two KGB officers who were more like probably what most of them were like, which is normal, relatable people doing a job, people we could understand and connect with and relate to just like we would hope that people in the Soviet Union or Russia today might be able to relate to CIA officers.”

Born in 1982, the year after The Americans begins, I’m just old enough to have seen Boris and Natasha on reruns of The Rocky and Bullwinkle Show and remember a few duck-and-cover drills (though growing up by California’s San Andreas Fault, we did them for earthquakes, not nukes). I’m too young to have known the threat of nuclear war, or to have understood, in second grade, what it meant when the Berlin Wall came down. By the time I knew much about Russia at all, the Soviet Union had collapsed and it was a weak, struggling country: as Donald Trump would put it, a loser. The vast, mono-colored area marked “USSR” in my older brother’s textbooks was suddenly now Russia and 14 other newly independent nations nobody knew the names of. Our side had won the Cold War, but rather than gloat over our victory, we should feel sorry for a country where the economy was in such a shambles that workers were paid in vodka.

Today, average Americans and Russians have more opportunities to interact with one another than ever before. Quirky Russian memes and dashcam videos travel over the internet, and Russian college kids staff American summer camps and amusement parks on the Jersey shore. Fewer Americans visit Russia than the other way around, but to some extent we now share a global pop culture. “Do you watch Stay Alive? How does it end?” a group of Ukrainian teenagers once asked me. (It was several days before I discovered they were talking about Lost.) American kids love the Russian animated series Masha and the Bear. Russians love Beyoncé.

The point of the Russian hacks was to let the US know its elections could be hacked, to sow confusion and piss in the orange juice of the democratic system.

On a personal level, I know how valuable it is to humanize the Other because I’ve been one myself. After spending years living and working in Russia and other parts of the former Soviet Union, I’ve been the first American someone has met more times than I can count. And the hours I’ve spent at Russians’ kitchen tables has helped me feel more compassion for people who do and believe things I don’t agree with.

During a visit to Russia in 2008, while watching President Putin and Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev on TV, my friend Tatiana said, “It makes me proud to see them.” When the two swapped roles in that year’s election — a move executed so Putin could become president again in 2012 without breaking the Russian constitution’s limit of two consecutive terms — she joked that she told everyone she knew to go out and vote for them twice.

Given reports of actual ballot stuffing, Tatiana’s comments made me cringe, as did Putin’s human rights record. But I understood that he made people like her, who’d lived through the economic tumult and national humiliation of the ’90s, who spoke no English and got most of their news from state-controlled television, feel that Russia could be great again.

But Putin — whose personal dislike for Hillary Clinton, whom he believes engineered the 2011 mass protests against him, is no secret — can’t have expected Donald Trump would actually win. The point of the Russian hacks was to let the US know its elections could be hacked, to sow confusion and piss in the orange juice of the democratic system.

Putin thrives on chaos and derives power from his ability to disrupt other countries’ relations and established order. In his efforts to influence the US elections, Putin has done exactly that, Russian journalist Yevgenia Albats recently told The New Yorker, to “show that, no matter what, we can enter your house and do what we want.” Russia may no longer be a superpower, but it can still move a lot of the West’s furniture. Italy has seen a recent coordinated onslaught of pro-Russian propaganda. France and Germany, which both hold elections this year, may be next.

Weisberg and Fields insist that current events haven’t influenced their writing — for example, Elizabeth and Philip won’t be crossing paths with their 1980s KGB contemporary, Vladimir Putin — and say the series is on track to end the way they’ve envisioned since Season 2. Without giving away spoilers, the first few episodes of Season 5 show The Americans doing what it does best: fleshing out the inner lives of characters who elsewhere would be stock villains or heroes, and allowing them to change, for better or worse, in response to their experiences.

It’s hard to watch a show about knowing our enemies just a few months after a bitter election campaign without seeing some domestic parallels. Americans might not be unified against a foreign enemy the way earlier generations were, but those of us in our mid-thirties or younger came of voting age in one of the most politically partisan times in US history. In lieu of the Soviet communists, our ideological foes, the people we feel most directly threaten our way of life, are likely to be our fellow Americans: liberals or conservatives, whoever is on the other side. The two major parties have always had different visions for America, but the chasm between them has never seemed this wide.

It's hard to watch a show about knowing our enemies just a few months after a bitter election campaign without seeing domestic parallels.

"The whole point is that national boundaries are no reason to pick enemies, and neither are political boundaries or political parties or any of the things we do to pick enemies within your own country," Weisberg said.

Increasingly, we live in different kinds of communities, get our news from different sources, talk about it in different spaces, and simply reject information that doesn’t support our point of view. Some of the hyperpartisan news sites that dominate our Facebook feeds are actually owned and operated by the same people, who present nearly identical stories with a few crucial tweaks tailored to appeal to conservatives’ and liberals’ senses of outrage.

“Facts don’t care about your feelings, snowflake,” conservatives tell liberals, while Americans across the political spectrum mourn the rise of “alternative facts” over any agreed objective reality. The “fake news” media, President Trump says, is the enemy of the people — the very same term Stalin used to send dissenters to the gulags.

“Free societies are often split because people have their own views, and that’s what former Soviet and current Russian intelligence tries to take advantage of,” former KGB general Oleg Kalugin told The New Yorker. “The goal is to deepen the splits.” As Adrian Chen has documented, some of the self-described “American patriots” pushing pro-Trump views on Twitter are actually paid Russian internet trolls. The Russian Foreign Ministry recently set up a website to discredit Western stories it says are false, providing no debunks, just the image of a red rubber stamp marked “FAKE: IT CONTAINS FALSE INFORMATION.”

There has been a lot of talk among us coastal journalists about the need to better understand the Midwestern, white working-class voters who sent Trump to the White House — a conversation that often overlooks the fact that plenty of struggling Americans who live in places like the Rust Belt are people of color. The counterargument says it’s really rural white voters who need to get out of their own bubbles and learn more about the rest of the world, and whatever motivated people to vote the way they did, they need to take responsibility for their choices.

When it feels like our very identity as a country is at stake, it’s easy to dismiss our political foes as so far beyond the pale that they’re unknowable, unreachable, even less than human. They’re not our neighbors: they’re treasonous idiots, “libtards” and “Trumpkins.” So I asked Weisberg and Fields how the show’s mission to “humanize the enemy” applies to domestic adversaries in these polarized times.

“It’s always somewhat dangerous territory for a TV show to have too much of a lesson to teach,” Weisberg said. “At the same time … if you can gain that way of looking at the world, that people you tend to demonize — instead of black-and-white cutouts — are complex people with good sides and bad sides, and for the most part are much more like you than you realize, then of course you can apply that to people within your own country.”

Humanizing your foes, Fields was quick to add, doesn’t mean letting them off the hook.

“All human beings live on a continuum of more and less moral, good and darker acts,” he said. “And the harder it is to humanize people who are doing things that feel wrong and maybe even are wrong, the more important it may be.

“Because if all we do is demonize, it’s hard to imagine how we make progress.”

Season 5 of The Americans premieres Tuesday, March 7 at 10 p.m./9 CT on FX.