Elizabeth O'Bagy, the controversial young researcher formerly with the Institute for the Study of War, was thrust into the media spotlight when her work was cited in congressional testimony and her previously undisclosed ties to an advocacy organization emerged. By the next week she had lost her job. Citing a misrepresentation of her credentials, ISW terminated her employment by close of business Tuesday.

The dust up began last week when both Senator John McCain and Secretary of State John Kerry cited O'Bagy's Wall Street Journal op-ed by name as they laid out their arguments for intervention in Syria during hearings on Capitol Hill. Both lawmakers and the WSJ referred to O'Bagy as simply a researcher with ISW. What they did not mention were O'Bagy's ties to another organization: The Syrian Emergency Task Force (SETF), a small pro-opposition advocacy group based in Washington, lobbying the U.S. government to intervene in Syria.

Throughout the original controversy surrounding O'Bagy's political ties, she said her research and her work with SETF were "completely separate." However she admitted that she and SETF sometimes held joint meetings with lawmakers and that occasionally her work with SETF benefited her in the field with greater access inside Syria. She says she's never hidden her affiliation with the advocacy group, but the connection was rarely made by journalists who cite O'Bagy's work. (Full disclosure: I also interviewed O'Bagy and cited her as simply a researcher a number of times while covering Syria for NPR and then for Syria Deeply).

"Objective analysis, I think, is an inaccurate term," O'Bagy said in an interview conducted before she was fired from ISW. "My research over the past two years has led me to very strong conclusions and to that degree I do have a significant bias."

The Researcher

Before last week, O'Bagy was an obscure, but respected figure in the small community of Syria watchers, researchers, and journalists that stretches from Washington to Beirut to Istanbul. Her work — an April 2012 report "The Free Syrian Army," her September 2012 report "Jihad in Syria," and her March 2013 report "Syria's Political Opposition" — provided one of the most comprehensive looks at Syria's armed and political opposition by a single researcher.

"While I consider it indefensible to misrepresent your credentials, especially when you're advising policymakers on a subject as sensitive as Syria, the zeal with which people are attacking O'Bagy is disturbing," said Hannah Allam, a journalist who covers foreign policy out of Washington, D.C. for McClatchy. She interviewed O'Bagy in her reporting on Syria and talked to her frequently over the past year. Allam took particular exception to criticism of O'Bagy's age. "A lot of the piling on comes from people who pontificate on Syria without ever having set foot in the country, without Arabic skills, without the courage to traverse a war zone at the mercy of ragtag rebel militias," Allam said.

But Allam also said she detected a gradual change in O'Bagy's statements over time: "Her initial findings were extremely informative to me and many other journalists." As the crisis in Syria wore on, however, Allam said O'Bagy began to display more overt support and sympathy for the Syrian opposition, while acknowledging problems among the rebel ranks.

When Allam saw O'Bagy's Wall Street Journal op-ed, she was shocked: "It not only contradicted what virtually every other astute observer of the conflict said, but also was at odds with some of her own assessments that she'd provided to McClatchy in interviews."

The Task Force

Early this summer, before Syria was at the forefront of the national agenda and before O'Bagy's name was in the headlines, the researcher was busy attending briefings with her colleague at SETF, executive director Mouaz Moustafa, a 28-year-old Syrian-Palestinian-American. O'Bagy and Moustafa spend a lot of time together and have the rapport of siblings. O'Bagy says their relationship is more "mother, son" than brother, sister.

"We're really acting as an extension of the United States Government," Moustafa said as he and O'Bagy walked out of a meeting at the Rayburn building on Capitol Hill in late July. "We've become a resource." Moustafa said the work they do fills in the gaps in the government's knowledge of Syria. "We can't even have foreign service officers inside the country and yet I'm in the country on a regular basis," he said.

SETF's Washington office is just off K street, less than a block from the White House. Despite the ritzy address, the setup is humble: a row of small windowless rooms. Above Moustafa's desk, the only decoration is a Syrian rebel flag tacked to the wall with pushpins.

The group acts as a clearinghouse for information from Syria that is then packaged and presented to lawmakers. Its funding comes from a board of trustees, a slate of politically active Syrian American doctors. Among them is Dr Zaher Sahloul, a medical doctor from Chicago who also serves as the current president of the Syrian American Medical Society, an aid group that travels in to Syria to deliver medical aid and supplies. SETF also works with the State Department through middlemen contractors.

"They're quite well-connected inside Syria," said a State Department official on condition of anonymity. "As there are no U.S. State Department personnel inside Syria, it is important for the United States to work with implementing partners who are able to access the Syrian opposition inside the country."

When asked if the State Department was involved in the advocacy side of SETF's operations, the official replied: "I'm not sure what you mean by advocacy." When asked a follow-up question about the possible conflict of interest resulting from State Department resources going to an aid group that was also lobbying members of Congress, the official replied: "The Department of State is not coordinating with SETF on outreach to Congress and our funds are not being provided to support lobbying."

A Trip to Syria

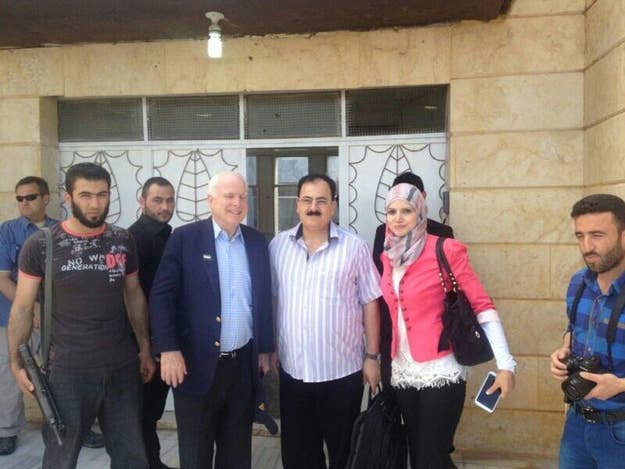

The Task Force has a particularly close relationship with Senator McCain. Earlier this summer before reports of a chemical weapons attack on August 21 spurred President Obama's push for US intervention, McCain slipped across the Turkish border into rebel held Syria for a secret meeting with the leader of the Free Syrian Army: General Selim Idriss. By his side were O'Bagy and Moustafa who planned and executed the entire visit, a chance to show a powerful U.S. lawmaker rebel held Syria first hand.

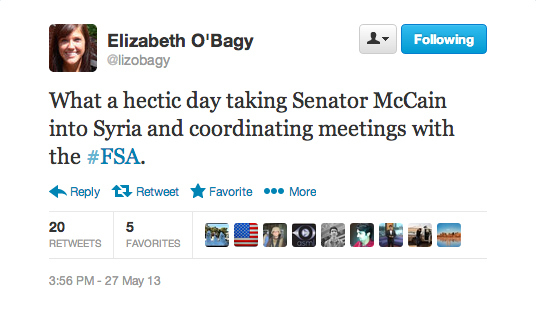

"What a hectic day taking Senator McCain in Syria and coordinating meetings with the #FSA," wrote on Twitter, from an account that she deleted after her firing.

Moustafa uploaded a picture of himself and McCain to his Instagram feed, captioning it: "With senator John McCain in free #syria"

The following week, on June 6, at a standing room only address at the Brookings Institution just off of Dupont Circle, McCain referenced his trip to Syria as he sounded the alarm on the "lack of U.S. leadership" in the post-Arab Spring Middle East.

"Our friends and allies in the Middle East are crying out for American leadership, as I heard again last week. We must answer this call," he said. McCain made a sweeping condemnation of U.S. Middle East policy that day, but ultimately, he focused on the country he had just visited. "An alternative strategy must begin with a credible Syria policy. I want a negotiated end to this conflict. But anyone who thinks that Assad and his allies will ever make peace when they are winning on the battlefield is delusional," he said.

McCain went on to lay out a plan for limited intervention in Syria, warning: "The longer we wait to take action, the more action we will have to take."

Once President Obama announced that he would seek authorization from Congress on a resolution authorizing the use of force in syria, SETF continued to lobby lawmakers, posting an "Action Alert" on their blog reading: "Contact your congress members to vote Yes on Syria."

As Senator Robert Menendez, Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, outlined his support for intervention in Syria in his opening testimony before a hearing on Syria, Moustafa tweeted:

Our multiple in person meetings with senator Menendez and the out reach from his Cuban and Syrian communities in NJ have paid off #Syria

Mouaz Moustafa

@SoccerMouaz

Our multiple in person meetings with senator Menendez and the out reach from his Cuban and Syrian communities in NJ have paid off #Syria

Blurred Lines

O'Bagy's firing set off a mini-media storm in Washington, with angry headlines labeling her Syria's Judith Miller and accusing her of spinning politicians. But in fact the dust-up touched at a deeper problem in Washington politics in general and the Syrian conflict in particular: the increasingly murky boundaries separating advocacy from research and journalism.

"These lines between between research and advocacy are getting more and more blurred," said James McGann, the director of the Think Tanks and Civil Societies Program at the University of Pennsylvania. McGann studies the intersection of research organizations, government, and policy and he says he has seen many cases of individuals acting as both researchers and advocates and failing to disclose both roles. "This is often where the problem is and where I have been ringing the alarm bell."

The crisis in Syria has proven a particularly difficult conflict on which to gather information. In 2012, the Committee to Protect Journalists labeled Syria the deadliest place in the world for journalists. Even for journalists and researchers who do venture into Syria, their vantage is often stunted by checkpoints, frontlines or regime minders. Journalists trying to cover Syria from afar are often forced to rely on information from agenda driven organizations.

Kim Kagan, the founder and president of the Institute for the Study of War, stressed that O'Bagy's termination was not related to her affiliation with SETF. "I had no problem with her affiliation, I approved it," Kagan said. "She led me to believe that she had successfully defended her dissertation and unfortunately that is not the case," she said.

O'Bagy got her BA from Georgetown University in 2009 and an MA from Georgetown in 2013, but not a Ph.D, as she had presented herself. When asked about earlier reports that O'Bagy was enrolled in a PhD program, but had not yet defended her dissertation, Georgetown University communications manager Rob Mathis replied: "All I can confirm at this time is that she earned those two degrees and is not registered presently."

Meanwhile, Moustafa's advocacy continues.

In early September, after a stressful week, Moustafa sat at his desk in the windowless office, he sounding exhausted: "It's not a win yet." He said victory for him would be seeing all members of Congress fully informed on Syria. If people just had good information from the beginning, he said, the U.S. would not be where it is now: "But just because we're late, doesn't mean we need to stop trying."