Black Panther is not the first superhero film of this modern “Cinematic Universe” era to try to say something. It’s not even the first Marvel film to try to say something. It is, however, the first to take a controlled political stance to reflect the uncertainty of our own world, which is something that seemed almost impossible, given that Black Panther arrived with the superhero movie machine conspicuously cranked all the way up.

There are generally three Marvel movies per year, one or two from DC, and then stuff from 20th Century Fox’s X-Men and X-adjacent franchise. The superhero machine is loud, and it churns out product that’s necessarily devoid of sharp political edges that might harm mass consumption; the simplicity of prototypical good vs. evil “comic book” conflict is part of the appeal. The various directors and writers involved may have their own voices and their own big ideas about colonialism, or bigotry, or surveillance, but against the hum of the machine, their cries are faint. It is in this context that Black Panther arrives, and for the first time, the clanging Marvel gears of marketing synergy and brand management have been overtaken by the distinct voice of writer-director Ryan Coogler.

In Black Panther, Coogler examines isolationist policy through the Afrofuturist country of Wakanda, prosperous beyond all imagination and never challenged by outsiders, because it conceals its power behind a veil of third-world poverty. The infant regime of our protagonist, King T’Challa (Chadwick Boseman), is beginning to gingerly reexamine this policy: While isolationism allowed Wakanda to thrive, it meant the country’s silence in the face of the imperialism and oppression inflicted on its neighbors in Africa. We’ll never know how an active Wakanda might have fought the slave trade or other injustices, and this is what fuels the righteous anger of the film’s villain, Erik “Killmonger” Stevens (Michael B. Jordan). As Doreen St. Felix writes for the New Yorker, Killmonger “shows us the limits of the Wakandan project — the people it leaves behind. Far from an archetypal nuisance, Killmonger is queasy and immature and beguiling, an Invisible Man living in a Marvel syntax.”

In asking difficult questions about whether a power like Wakanda should intervene, and how it should go about that intervention, Black Panther demonstrates an ethical complexity that does not extend to the rest of its franchise, or to much of its genre these days (despite how entertaining other superhero fare can be). For Shadow and Act, Brooke Obie observes, “It makes sense for Wakanda to put up an invisible shield, play on the world’s Anti-African racism and protect itself from white ravagers without having to spare any one of their lives in battle. But, there is a cost.” And Black Panther doesn’t shy away from articulating — and forcing its hero to acknowledge — what that cost has been. Coogler’s ability to deliver a movie like this, which has seen rave reviews and a historic four-day box office gross rivaled only by Star Wars: The Force Awakens, not only shows that such work can exist within an otherwise stifling studio system, but raises the bar for everything that comes after it.

Marvel’s Iron Man began in Afghanistan in 2008, with a wartime scene Sean Fennessey of the Ringer described as “an inciting incident for an expanding universe, a place setting for a Happy Meal.” But Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014) marked Marvel’s first venture into serious social commentary. Early on, Cap and Nick Fury debate the merits of a new security program that will send killer drones out on patrol, launching preemptive strikes on terrorists before they can raise any terror. Cap calls it fear, not freedom. Fury cites the necessity of vigilance “after New York” in reference to the alien invasion at the end of The Avengers, but what the film means is 9/11.

These drones are not, after all, weapons from some threatening outside force that the two are equally horrified about; these are weapons developed by the United States to safeguard the United States, representing years of post-9/11 paranoia and boundary fudging. The filmmakers were clear on this in a 2014 interview with Mother Jones: “[A]ll the great political thrillers have very current issues in them that reflect the anxiety of the audience…That gives it an immediacy, it makes it relevant. So [Anthony] and I just looked at the issues that were causing anxiety for us, because we read a lot and are politically inclined. And a lot of that stuff had to do with civil liberties issues, drone strikes, the president’s kill list, preemptive technology.”

The Winter Soldier is often called a Marvel highlight, and one of the best superhero films in general, in part because it takes a stance on such a relevant issue. Even the Rotten Tomatoes summary calls it “politically astute.” But by the end of the film, what starts as a bold callout of the supposedly good guys devolves into a plot that lets the United States government off the hook, by clarifying the origins of its corruption: strictly foreign. It was all orchestrated by Hydra, a group of former Nazis that broke off from the Third Reich in the previous film (presumably because action figures are an easier sell without the swastikas). As if to underscore how separate Hydra is from all those altruistic American hearts pumping red, white, and blue, the film reveals their infiltration through the cold, inhuman voice of a dead guy whose consciousness lives on in one of those old computers that only displays black and green; not us, them.

There is, to be fair, some inherent commentary in the idea that Fury’s security program, at first an echo of our own government overreach, is actually concocted by the Bad Guys. But it’s too easy. It reduces complicated ethical questions about civil liberty to basic villainy, and Black Panther is careful to avoid the same mistakes. Killmonger is motivated by watching and suffering years of prejudice, by knowledge of an extensive history of wrongs, and the film never diminishes that anger by revealing racism to be the diabolical scheme of Thanos or something. Though the film is critical of Killmonger’s horrific methods, it also keeps in mind the white supremacist systems that drove him to the point at which he wants to start a global race war. Killmonger threatens and kills anyone in his way, but Black Panther never loses sight of his main grievance — that Wakanda has the power to do something about the suffering it otherwise ignores. As such, it achieves an ambiguity that may be limited, or imperfect, but that no other cinematic universe entry so far can claim.

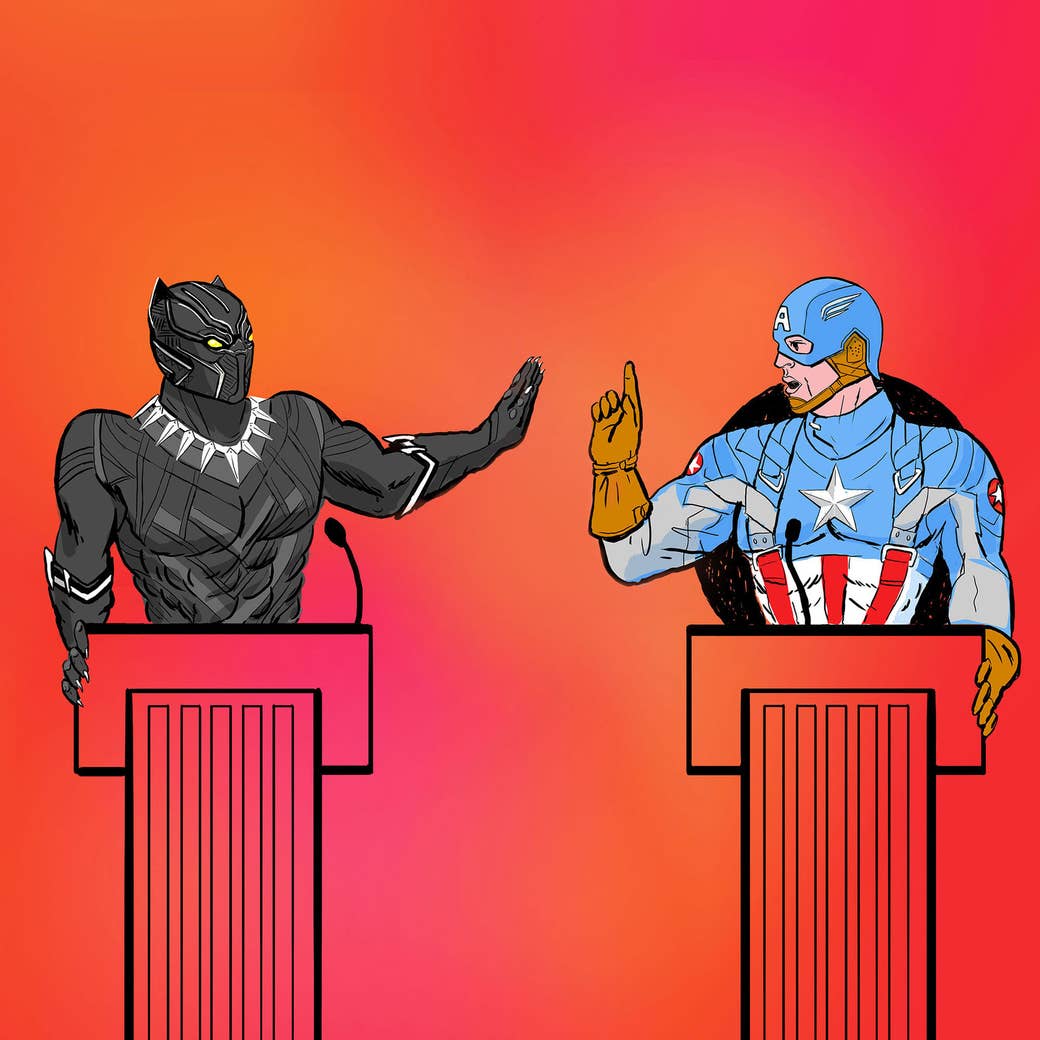

The most recent Captain America film, 2016’s Civil War (which was also Black Panther’s intro to the MCU) attempted a similar ambiguity. Whereas there’s no real reason to doubt Cap in The Winter Soldier, Civil War voices an opposing perspective through Iron Man. Tony Stark’s proposal for government oversight is based on a valid argument; when a mission goes wrong, as it does at the start of Civil War, the Avengers don’t answer to anyone. Cap remarks that being beholden to governments means being beholden to government agendas, but it doesn’t diminish Tony’s point; the other Avengers proceed to pick sides.

Marvel meant to show us that they took this conflict seriously, even more seriously than the political ambitions of The Winter Soldier. The movie’s marketing went so far as to ask “Whose side are you on?” as if there were any question, with the two opposing factions draped in the colors of the two major US political parties. But as Civil War goes on, it tables the oversight debate (having served its purpose to divide everyone up into dodgeball teams) in favor of the pursuit of Cap’s old war buddy Bucky Barnes, who was already deployed once as a kind of decoy villain in Winter Soldier. A supposedly balanced conflict turns into a concerted effort to show how misguided, erratic, and emotional Stark is. The film even shows that the side Stark has chosen is wrong, when he stands dumbfounded at the sinister underwater gulag where the world governments have left his friends to rot. Cap walks away with the moral high ground, having learned only that he was right all along.

Coogler’s Black Panther does not discount the merits of the other side, as Civil War does with Stark, and as a result T’Challa actually grows. We admire T’Challa, because he is funny and warm and committed to his principles. He is a sympathetic figure who confers with his family and friends about what’s best for the country, though he remains conflicted about the isolationism that characters like Lupita Nyong’o’s Nakia push him to abandon. What ultimately spurs him to action is Killmonger’s pain, the anguish T’Challa has been shielded from by the safety of his home country; Killmonger lashes out at not just white privilege, but at a Wakandan privilege that did not follow him to America, to Oakland where his father was murdered. Black Panther gives its villain the space not just to present his views, but to let those views seep into the film’s overall message and reshape the perspective of its protagonist. As Adam Serwer writes for the Atlantic, “Killmonger does something remarkable and perhaps unprecedented for the superhero genre — he wins the argument.”

It's significant that Coogler manages all this at the end of Black Panther; so many superhero movies lose their themes in the inevitable third-act CG action climax, because it is difficult to keep a firm grasp on politics and a crowd-pleasing special effects throwdown at the same time. In Patty Jenkins’ Wonder Woman last year, for example, the ending battle only underlines the central confusion of an otherwise successful narrative; Diana spends most of the movie convinced that by killing Ares, the god of war reincarnated as a German general, she will end World War I. Then, pre-throwdown, she learns that Ares was actually someone on her side, and that humans started this horrifying conflict themselves without any divine interference.

This twist is, in many ways, an intended rebuttal to the binary conflict we expect in our superhero movies, especially our Captain America films — there’s no evil organization to blame for basic human monstrosity. But couched as it is in simplified wartime conflict, Wonder Woman still brushes up against that binary. Within the first 30 minutes of the movie, Diana’s love interest explains that he’s one of the good guys and those Germans over there are the bad guys, and the film never really disputes this. Diana’s side has its own bad guys — the generals with a callous disregard for soldiers’ lives — but their crimes feel small compared to the cackling villainy of the German general who poisons his colleagues to keep them from ending the war, or the German regiment that enslaves a whole village. Although Ares’ revelation restores some ambiguity to the WWI backdrop, Diana’s battle with him for the fate of mankind falls right back into old-fashioned good and evil. Out of context, his ravings about how humans deserve destruction sound an awful lot like the final boss of a video game.

Superhero films are designed for the mass market, so it follows that their themes must be palatable. Good and evil conflicts are comfortable. They go down easy in films that are also designed to go down easy, and the thing that goes down easiest of all is reassurance. We like to dwell on big issues that let us feel intelligent and engaged, but we most appreciate being told, in the end, that everything is fine.

Many of these more political superhero movies split the difference. The Winter Soldier seemingly wants to send a message that it’s tearing the system down through the sheer bombast of the crumbling buildings that belong to evil government agencies, yet it is also careful to extricate Hydra from the US at large. Civil War makes Cap a fugitive while leaving no doubt that he did the right thing. The parodic darkness of Batman v. Superman says its heroes are monsters until they meet the actual monster. Wonder Woman asserts that there’s evil on both sides, before retreating to binary conflict and the good people who are worth fighting for (an inspirational sentiment that does, at least, fare better than the others).

These films offer us conflict and encourage us to ask questions, but they do so within a confined space. Nothing strengthens complacency like getting us to question, just for a moment, if everything truly is fine — before returning us to the warm comfort of the status quo, where it’s all okay, just as we suspected. How political can these films be when, by letting the good guys triumph in a reductive conflict, they inevitably retract their moral complexity and compromise their advocation for change? Many hardly bother to engage at all; you can see this aversion to social issues in a movie like X-Men: First Class (2011), which rebooted the inherently political franchise with a 1960s setting that involved not a peep about civil rights.

The closest any of the recent crop of superhero franchises have come to a coherent statement prior to Black Panther was the previous Marvel film, Taika Waititi’s Thor: Ragnarok (2017). It reveals that the mythical Nordic realm of Asgard was founded on blood and conquest, a past literally paved over when they replaced the tacky throne room ceiling painting that commemorates the bloodshed with something more tasteful. Thor’s response to this revelation is to destroy Asgard and start over, and for a whole four months it was one of the most radical sentiments ever put forward by one of these cinematic universes. But Thor’s idea of a do-over doesn’t really indict the complicit ruling class, nor does it say anything about (or even show) the victims of colonialism. It’s still a Thor movie, after all, so they leave the god of thunder on his throne and roll the mid-credits scene.

This is not to say the politics of Black Panther should escape scrutiny; its professed solution of outreach programs and UN speeches is not exactly a middle ground between complete isolation and Killmonger’s agenda, and any familiarity with the United Nations might lead you to snicker at Marvel’s weird optimism. Wakanda is still, at the end of the movie, a country ruled by a monarchy (and one rescued in part by a CIA agent, at that). But even so, Black Panther is the most coherent political statement these blockbuster franchises have yet produced, an unapologetic argument for sweeping change that doesn’t blink in the face of the crowd-pleasing action that got people to buy all that popcorn. It instead holds our gaze, and argues the duty of the powerful to the disenfranchised. In this, it succeeds where so many films created within the cinematic universe system have stumbled, and it clarifies what such films can be if only they are allowed to step beyond their usual pacifying constraints.

Superhero films are some of the most widely seen entertainment on the planet, so isn’t there some sort of responsibility — or at least opportunity — there? They have finally begun to use their platform for representation behind the camera, in Thor: Ragnarok, and on both sides of it with Wonder Woman and Black Panther; isn’t it also time to take the next step and argue the relevant social issues these films already bring up without pulling those punches before it’s time to leave?

Black Panther is a mass-market product, as all these other films are, but it shows that such products can still engage with complex topics. The film trades in empowerment and inspiration and thrills, but it leaves plenty of room for ethical questions, for ambiguity in a sympathetic villain and a hero whose perspective is not necessarily the correct one. It challenges us to reckon with the really important moral stuff while avoiding easy outs, and it hasn’t driven people away. Instead, audiences have embraced it with a fervor that should torpedo the passionless, noncommittal themes to which we are accustomed. Coogler’s film proves that it’s possible to do all this without compromising the expected spectacle; it shows us what these movies should have been doing all along. ●

Steven Scaife is a freelance writer based somewhere in Ohio. His work has appeared at the Awl, Vice, Paste, Slant, Zam, and SyFy.