23andMe bills itself as a company that "democratizes personal genetics" for the world. And that description's not necessarily all that far off: For $99, customers spit into an at-home kit, mail it in, and then go online to learn about their ancestral origins and far-flung relatives.

But consumers also get their raw DNA, in the form of big, downloadable spreadsheets filled with rows of genetic code, and they can do whatever they want with it — and thanks to 23andMe's open API, developers can do the same. Sometimes, this democratization of information yields more than what 23andMe likely bargained for.

This week, an anonymous programmer posted on GitHub an early-stage program called Genetic Access Control. It basically worked as a log-in mechanism. The third-party program was designed to hook up to the company's API and mine the 23andMe accounts of users who agreed to share their information, as they would agree to let apps connect to their Facebook or Twitter profiles. Websites using Genetic Access Control could scan that data for information about "sex, ancestry, disease susceptibility, and arbitrary characteristics" — and then restrict users' access to the site based on this information.

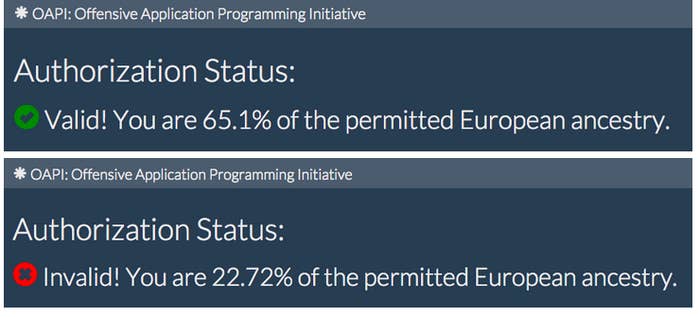

For example, people with only the "right" amount of European ancestry would be allowed to access a website that used Genetic Access Control:

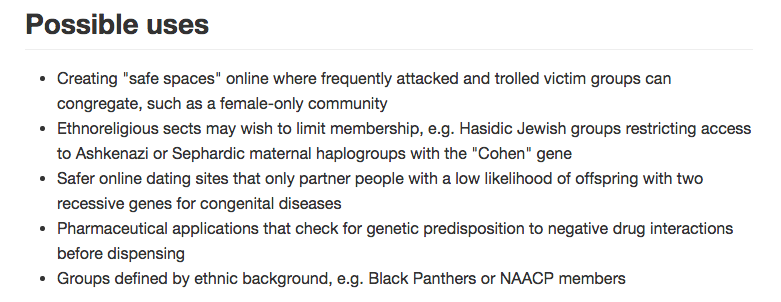

Other suggested uses, according to Genetic Access Control:

But 23andMe shut down the developer's access to its API on Wednesday, two days after the code was published. 23andMe spokesperson Catherine Afarian told BuzzFeed News the program violated a policy that forbids use of the API for, among other things, "hate materials or materials urging acts of terrorism or violence."

Developers can use 23andMe's API to initially develop and test an app with up to 20 users, so no more than 20 people could have used Genetic Access Control (and in fact, only three people used it before it was shut down, Afarian said). Once an app is built, the developer has to get permission from 23andMe to open it up to more users, Afarian said. So it's safe to say that the startup wasn't going to let Genetic Access Control go very far.

Still, the incident speaks to the wide range of unpredictable and unvalidated uses for personal DNA information once it's unleashed in the world. 23andMe, which has collected more than 1 million DNA samples, celebrates happy stories of reunions between long-lost relatives and of adoptees who used the service to discover their true ethnic makeup. But genetic code is more than just a neutral chain of letters laid out on a spreadsheet: It's a historically and culturally fraught concept that has been used time and again not to forge connections between people and create camera-ready reunions, but to exclude individuals and groups and perpetuate systems of oppression. The flip side of all that information is the potential for discriminatory, misleading, and upsetting use.

And even if 23andMe continues to shut down projects that use its data for openly exclusionary ends, there are all kinds of unintended consequences to releasing information as weighted and personal as genetic information. DNA testing has already led people to learn things about their origins that they didn't necessarily want to learn. Third-party developers have built dozens of programs that used raw DNA to do everything from suss out cousin marriages in a lineage to compare different readouts of the same genome to look for errors.

23andMe can no longer tell people about virtually all inherited health risks, due to a U.S. Food and Drug Administration crackdown on direct-to-consumer genetic testing in 2013. But that hasn't stopped people from taking their raw DNA to unregulated sites like Promethease, Interpretome, LiveWello, and Genetic Genie and getting (likely inaccurate) information about their health — information that they could use to make potentially life-changing decisions.

23andMe may have nipped its Genetic Access Control problem in the bud, but it's a problem that will likely rear its head again elsewhere and in different form. Because once the world is given access to its DNA, companies like 23andMe don't have the final say over what happens next.