Individuals hoping to learn about their lineage or see how closely related they are to Neanderthals aren’t the only ones interested in the DNA tests sold by 23andMe — the FBI and other law enforcement agencies are, too.

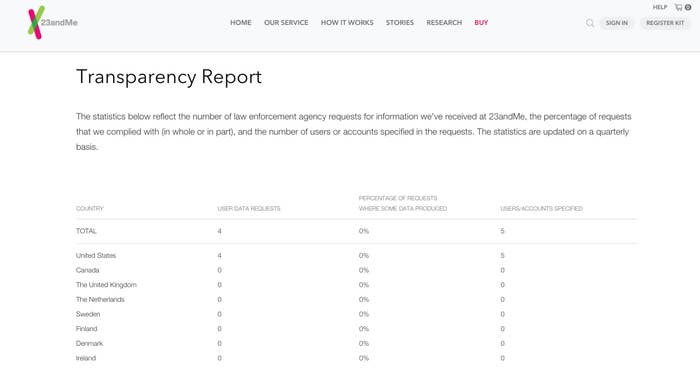

In a transparency report published Wednesday, the direct-to-consumer genetic-testing startup revealed that law enforcement officials have requested five customers’ data over the course of the company’s nearly decade-long history. 23andMe says it hasn’t provided data in any of those cases.

“We’ve successfully fought all of those requests and we’ve had to provide no information to law enforcement,” said Kate Black — who became 23andMe’s first privacy officer in February — in an interview with BuzzFeed News. “That’s something we’re really proud of. I personally am dedicated to ensuring that we never have to give that kind of information.”

The FBI maintains its own national DNA registry of convicts and arrestees, but 23andMe has more than 1 million DNA samples (a number that may grow as the company reintroduces health-related tests), many of which aren't already part of government registries. It’s not hard to see why law enforcement would be interested in them.

Indeed, as Wired has reported, earlier this year a New Orleans filmmaker briefly became a suspect in a murder case based on a saliva sample his father had given to an Ancestry.com database. Ancestry.com, Fusion noted today, has also faced law enforcement requests for customer data, but it hasn’t revealed how many.

23andMe’s privacy policy warns customers that their information could be handed over in the face of a court order, warrant, or similar legal or regulatory inquiry. Since CEO Anne Wojcicki co-founded 23andMe in 2006, it’s received a total of four requests about five people: Three from state agencies, one from the FBI working with a state agency. Only two of the requests were legally valid, Black said, adding that the requests, though small in number, have increased in the last few years.

One of 23andMe’s main lines of defense for protecting data is that the person who orders a mail-home “spit kit” online is not necessarily the one who submits a sample. Cops curious about a 23andMe customer’s DNA — and if, say, it matches a sample found at a crime scene — therefore can’t be certain that the DNA in fact belongs to that person.

“We don’t authenticate who they are, and you can’t follow the chain of custody for saliva or spit from any customer in particular to our database,” said Black, who oversees a team of four employees dedicated to privacy issues. “Under those circumstances, the evidence doesn’t hold up in court.” She declined to discuss specific details of the cases.

23andMe says it will update its transparency report every quarter.