Ancestry.com, which has collected the DNA of 1 million amateur genealogists, appears to be positioning itself to compete with rival 23andMe in a potentially enormous yet tightly regulated and so far untapped market: health.

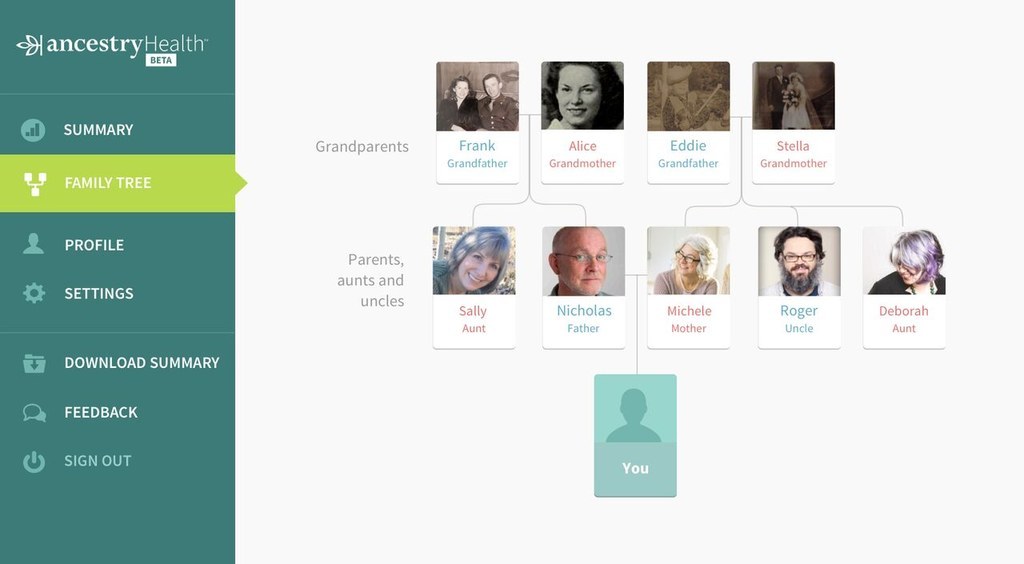

Since Ancestry.com started selling DNA kits in 2012, it's been in the business of linking customers' genotypes to their family history to unearth long-lost relatives. On Thursday, it's adding a twist to that equation by letting users manually add health conditions to their family trees.

Under current federal regulations, Ancestry.com isn't allowed to tie all those dots together: It can't directly use its massive personal DNA database to interpret most inherited health risks. Neither can 23andMe or other direct-to-consumer genetic testing companies. Still, the new features are setting the stage for what Ancestry.com executives hope will someday be a robust genetics-and-health business — an area that the company has been hinting at for almost a year.

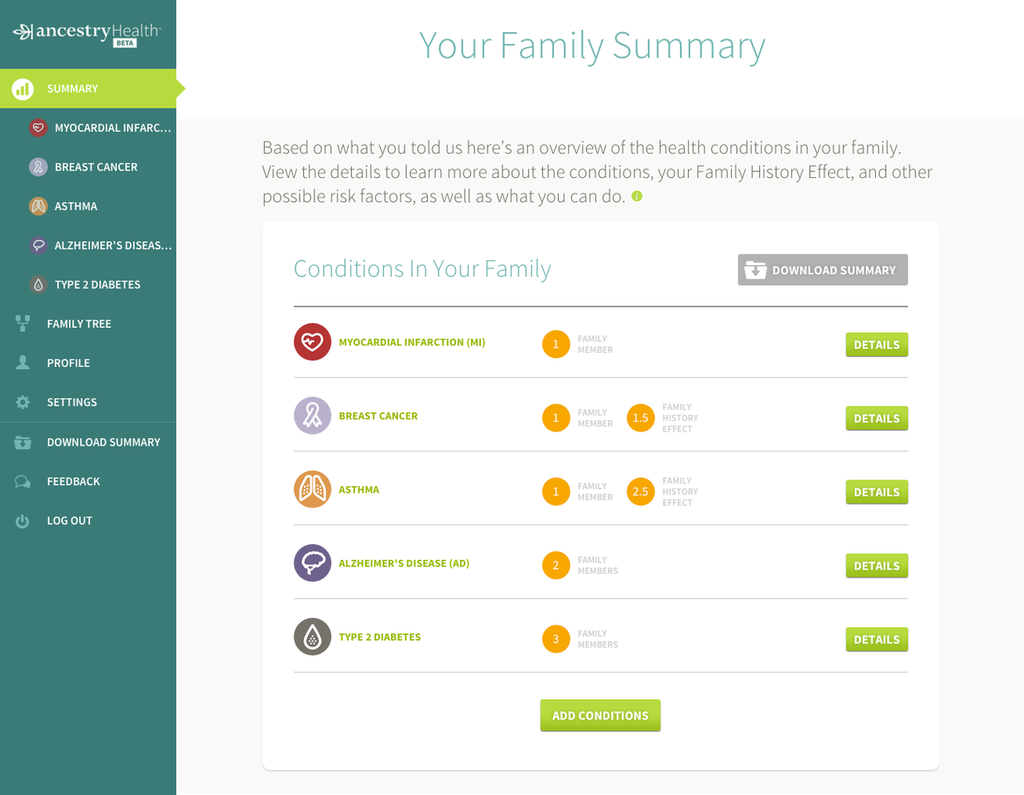

By looking at users' self-reported data and matching it with trends in peer-reviewed studies, Ancestry.com's new health site hopes to offer people general information about their potential health risks. If a woman notes that several women in her family developed breast cancer under age 50, for example, the site might tell her that she's at an increased risk for the disease and suggest that she get tested.

Ken Chahine, executive vice president and general manager of AncestryDNA and AncestryHealth, imagines a day when a doctor can look up a patient's family health history at a glance — ideally, on Ancestry.com — and better treat them. "The goal is precision medicine," he said. "That's what every developed country certainly wants. What's been keeping us from doing that is no one's been able to integrate all this information in a way that can meaningfully give an individual a precise risk assessment of themselves."

But for now, while customers can build a history of their family health, the site won't interpret their genotypes to tell them about their health risks, or connect them with a genetic counselor or a doctor. "We obviously are very clear that these are high-level risk assessments and they're based simply on family history, which is really, really important," Chahine said.

There's good reason for that. The business of using that data to infer genetic health risks, without a licensed medical professional as an intermediary, is a fraught regulatory area where other companies have stumbled.

Most notably, 23andMe was forced to stop telling customers about their inherited health risks in November 2013 when the Food and Drug Administration cited concerns about the tests' accuracy. The blow wasn't fatal, however: In February, the FDA loosened its regulations to allow specific tests for people who show no symptoms for a genetic disorder, but may be at risk for passing it on to their children. That included a 23andMe test for a rare hereditary condition called Bloom syndrome.

"I think a lot of people in the field feel that was the first of hopefully many different classes of direct-to-consumer genetic testing that will be approved in the future," Chahine told BuzzFeed News. "We don't know what those are."

Though rules for this emerging field have yet to be ironed out, Ancestry.com wants to be prepared for a future in which companies can use DNA to infer health risks. And in that scenario, companies would benefit from having as much personal DNA as possible. The bigger and more diverse the genetic database, the more information that can be mined from it. Ancestry.com said Thursday that it had collected 1 million samples, but its main rival, 23andMe, hit that milestone last month — and is becoming a drug developer in and of itself.

Ancestry.com is betting that many of its genotyped customers will want to know something about their health in addition to their lineage. So to bring as many people into the fold as possible, the company is offering its new health service for free to existing and new customers.

And to help guide it through the FDA, the company has hired a chief health officer, Dr. Cathy Petti, a former executive in the biotechnology and medical laboratory industry. "We're going to basically begin to talk to regulators and figure out how to responsibly offer some of the health related information that comes from your genome to consumers," Chahine said.