The journalists at BuzzFeed News are proud to bring you trustworthy and relevant reporting about the coronavirus. To help keep this news free, become a member and sign up for our newsletter, Incoming.

When Nicholas White decided to launch a clinical trial about hydroxychloroquine, he didn’t know he’d picked the soon-to-be most controversial drug in the world.

Early on in the pandemic, his research team set out to see if the malaria medication could prevent coronavirus infections, something test-tube research hinted at. Their goal: to sign up 40,000 healthcare workers.

The count, since April: about 100.

Months ago, trials like this one were flooded with volunteers eager for hydroxychloroquine. Just as quickly, its moment faded. At least four prevention trials have struggled to find enough people willing to take it, so far falling short of their collective goal of recruiting tens of thousands of participants, BuzzFeed News has found. Their uncertain fate shows how science has become more politicized than ever. But it also makes clear that drug research is a chaotic mess.

White, a tropical medicine professor at Mahidol University in Bangkok, never dreamed that President Donald Trump would baselessly call hydroxychloroquine a “game changer,” or that a fraudulent study would cast a pall over the field. But he also didn’t anticipate that, when confronted with one of the pandemic’s most urgent priorities — finding safe, effective treatments — the scientific community’s response would be so disorganized that it would squander time, funding, and, perhaps most crucially, willing participants.

The result is paradoxical: Hydroxychloroquine was one of the most heavily studied drugs this spring, and study after study has shown that it’s not an effective treatment for sick patients. But scientists still don’t, and may never, know if it works as a prophylaxis that prevents infections.

“The fact that it’s August and it’s still an open question is an embarrassment,” Walid Gellad, who leads the Center for Pharmaceutical Policy and Prescribing at the University of Pittsburgh, told BuzzFeed News.

Bad publicity certainly hasn’t helped. Some participants who chose to drop out of the trials told researchers that they believed the drug was universally dangerous, although that isn’t quite true. Safety concerns have been raised about its effects in hospitalized COVID-19 patients, as well as about high doses of its sister drug chloroquine.

The deeper systemic issue is that there have only been a handful of large, rigorous trials for hydroxychloroquine or, for that matter, any potential treatment. These randomized controlled trials, where some people receive a treatment and others a placebo, are the gold standard in medicine for determining if a drug works.

In the near-absence of coordination among national and global health agencies, separate clusters of scientists have run smaller, less definitive trials. And for months, the FDA allowed hydroxychloroquine to be given to COVID-19 patients outside of clinical trials. That further drained the pool of people who might be willing to enroll in a trial and risk getting a placebo, in turn muddling the evidence about what worked and didn’t.

History is now repeating itself with convalescent plasma — the liquid in blood that remains when blood cells are removed. Coronavirus survivors’ plasma contains antibodies, which early studies suggest could help others fight off infections. But no randomized trials have proven that so far, or answered crucial questions like what dose works best or on which patients, and studies are struggling to enroll enough people. Now they will likely have an even harder time finding volunteers, as the FDA just authorized hospitals to treat COVID-19 patients with plasma.

White and his colleagues are frustrated, to put it mildly. Hydroxychloroquine, they complained in a press release this month, was “being prematurely discarded in COVID-19 prevention.” Two recent prevention studies have come up negative, but outside experts say they are not the last word.

“I would like to have seen genuine coordination to do large and definitive trials, and I think that could have happened,” White, who is also affiliated with the University of Oxford, told BuzzFeed News. “It didn’t.”

It’s unclear what will happen to his team’s study, which, along with two other institutions, is sharing a $20 million grant from big backers like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the Wellcome Trust, and Mastercard. “I don’t know if the drug works or not, I really don’t,” White said. “But what I do know is we don’t know whether it works, and I also know we really need to find out.”

When a mysterious, deadly pathogen began spreading beyond China’s borders this winter, scientists worldwide embarked on a desperate hunt for treatments. A cure from scratch would take precious time, so they scoured the literature for a drug that already existed for other conditions, one that might also be capable of taking on this new coronavirus.

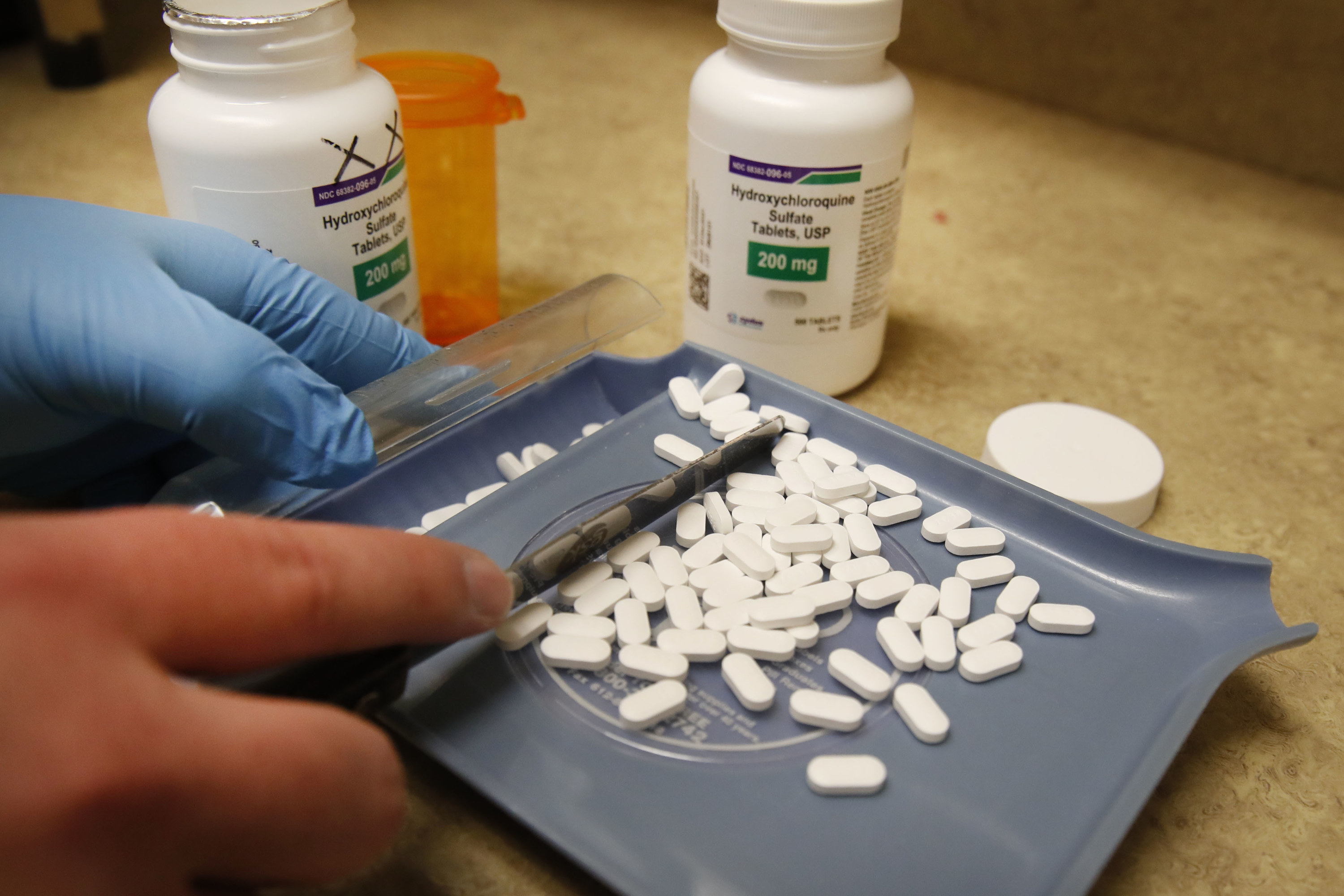

Hydroxychloroquine quickly rose to the top of the list. Approved in the US since the 1950s, it is a less toxic version of chloroquine, an antimalarial drug, and also used for lupus and rheumatoid arthritis. In the early spring, lab studies were indicating that it could inhibit SARS-CoV-2 in infected cells. Some scholars advocated for giving it a shot as a preventive measure.

“There was nothing else that was really potent against coronaviruses, SARS-CoV-2 in particular,” White said. “These drugs are inexpensive, widely available, could be deployed immediately, and safe.”

Ruanne Barnabas of the University of Washington said her motivation for doing a prevention study — unrelated to White’s — was to answer the question one way or another. She was concerned that India had started using hydroxychloroquine as a preventative without robust evidence.

“It’s not a good use of resources if it doesn’t work,” said Barnabas, an associate professor of global health and medicine. “We should be focusing on every dollar spent. We needed a clear answer here for hydroxychloroquine for prevention.”

They were hardly the only ones studying the drug. As of July, scientists had designed 1,200 trials to study treatment or prevention of COVID-19 — and one out of six was about hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine, according to a Stat analysis. Similarly, researchers have reported that nearly one-quarter of coronavirus-related randomized trials this spring involved a drug in the chloroquine family. They’ve been studied in doses high and low, taken alone and combined with vitamins and antibiotics, and in all sorts of patients.

But almost from the start, the buzz around the medications was confusing, politicized, and seemingly contradictory. In March, a French scientist touted hydroxychloroquine as a coronavirus treatment on the basis of a small and widely condemned study. Trump then pressured the FDA to authorize it, at one point reportedly taking it himself, and people rushed out to hoard it. Then the FDA warned that it could cause irregular heart rhythms in hospitalized patients.

In another confusing turn, an explosive study published in the Lancet in May linked hydroxychloroquine to a higher chance of death — only to later be revealed as fraudulent and get retracted. Even so, United Kingdom researchers reported in June that a massive trial showed no benefit, leading the FDA to yank back its authorization.

Meanwhile, a handful of scientists were still trying to investigate whether hydroxychloroquine could prevent infections. But participants were getting harder to find. Out of an abundance of caution following the Lancet study, the World Health Organization paused a hydroxychloroquine trial it was running, and White did as well, setting his research back weeks.

In April, a study led by the Duke Clinical Research Institute set out to enlist 15,000 healthcare workers. Now, they’re hoping for 2,000. With about 1,240 enrolled as of mid-August, they still don’t have enough people.

“Our highest enrollment was in our second week,” said Susanna Naggie, a Duke professor overseeing the study. She projected that the numbers would have kept going up, but “that just didn’t happen.” She blamed the constant commentary from politicians and the media — “every story bent slightly to whatever the preference of that audience might be.”

The prevention study at the University of Washington currently has more than 800 healthcare workers, with a target of 2,000. Recruitment since late March has been “steady,” Barnabas said, though “affected by the news cycle from time to time.”

A team of researchers from the University of Minnesota and Canada has conducted two prevention studies. The second began recruiting in April, when hydroxychloroquine was in the news more. “People went from everyone wanting to try this drug to nobody wants anything to do with it,” said that study’s leader, Radha Rajasingham, an assistant professor of infectious diseases and international medicine.

While she declined to discuss the results, since they aren’t published yet, she admitted that they will not be conclusive due to their sample size. Enrollment came to just under 1,500 people, less than half of the original target of 3,200. “We stopped our enrollment early because we had so few people enroll by the end, because of the negative press,” she said.

From the get-go, she said, the drug was controversial on both the right and left.

“Earlier on, people felt like it was unethical for us to even study this,” Rajasingham recalled. “They felt it was obvious hydroxychloroquine worked. Another group felt it was unethical for us to study this because it obviously didn’t work.”

White conceded that it isn’t surprising that people would be reluctant to join the drug’s prevention trials.

“I can understand the general public being a bit confused and suspicious,” he said. “I would be too.”

Despite the glut of hydroxychloroquine trials, only a few have been big enough to produce solid evidence about its effectiveness. Widely regarded as the most robust is the UK’s Recovery trial, which found in June that the drug was an ineffective treatment on coronavirus patients.

It was one of several potential COVID-19 therapies tested across the country. In more hopeful news, the Recovery trial also found that dexamethasone, a steroid, reduced death by up to one-third in patients on ventilators.

Due to the large number of participants tested, these findings have been taken seriously. The trial last reported that it had enrolled upwards of 11,800 patients from more than 175 hospitals, making it the biggest randomized COVID-19 trial in the world. In its hydroxychloroquine arm alone, 1,500 people were given the drug and compared to more than 3,000 who received standard hospital care.

Nothing on that scale happened in the US. “Over 100 separate groups decided to do 100 separate hydroxychloroquine trials,” said Derek Angus, chair of critical care medicine at the University of Pittsburgh. “No one needs 100.”

The key difference comes down to this: Unlike in the UK, where the National Health Service can coordinate clinical research through its vast network of public hospitals, research in the US is not set up to operate as a cohesive whole. In the system as designed, warring factions — pharmaceutical companies, academic medical centers, individual scientists — jockey for money for their own trials.

“And so when there’s some sort of existential crisis and the whole world needs to band together to generate information as quickly as possible,” Angus said, “it turns out that no one has a mechanism to promote cooperation.”

There are some exceptions. The Duke-led prevention study is funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, which is enrolling participants at a network of 30 research sites across the country.

NIH-sponsored clinical trials were also carried out at medical centers nationwide, finding benefits for the antiviral remdesivir and yet another negative finding for hydroxychloroquine as a treatment.

Even so, those two trials had about 1,500 patients combined — a fraction of the Recovery trial. As Angus, who helped conduct the NIH’s hydroxychloroquine trial, put it: “Every single part of the process isn’t really built for speed.”

Which means that some trials are still getting going. To this day, the database ClinicalTrials.gov is littered with planned hydroxychloroquine studies around the world. As of mid-August, at least 80 trials to study it as a treatment for COVID-19 or conditions caused by it were listed as planned or active. (BuzzFeed News was unable to verify how many were truly ongoing.)

Theoretically, this research could go on forever — studying various doses, starting at different points and for different lengths of time, or in combinations with other treatments. But “in a world where we have limited resources, you can’t do every possible scenario for every drug,” said David Fajgenbaum, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

Many researchers agree that, at least as a treatment, hydroxychloroquine is over. Paul Garner, a professor at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, is coordinating the Cochrane review of all research of the drug’s effectiveness. That analysis isn’t out yet, but Garner said, “I haven’t seen a single scrap of evidence, from my eyeballing of it, of any benefit.”

Donald Berry, a biostatistician at MD Anderson Cancer Center and clinical trial consultant, is highly skeptical that prevention will be a different story.

“If a trial is going on with hydroxychloroquine in the prevention setting, you have to really consider, ‘Why am I doing this?’” he said. “There are a gazillion therapies in the world, why hydroxychloroquine?”

He has a point. So far, two trials have found that hydroxychloroquine did not seem to ward off coronavirus infections in people who took it shortly after exposure.

Outside researchers say these results are not definitive. In one of the studies, involving 2,300 people in Barcelona, participants were told which treatment they were receiving, which could have skewed the results. And the 800 or so people in the other — which was led by Rajasingham and colleagues at the University of Minnesota — were not uniformly tested for the disease.

These studies also both tested the drug as a preventative after someone was exposed, but before they got sick. Other researchers are now studying what happens when people take hydroxychloroquine before exposure. But it’s unclear whether they’ll get answers.

White is coming to grips with the reality that his trial is unlikely to finish by the end of the year as planned, if ever.

“We are determined to try. I’m not sure whether we’ll succeed,” he said. “It’s a bit sad that the most talked-about drug in the world for the last six months, we just don’t know whether it works or not.” ●