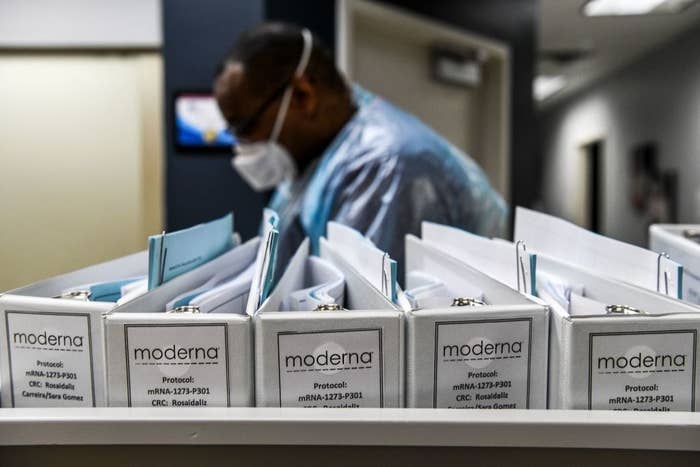

In a scramble to restore fading public trust in the coronavirus vaccine pipeline, two leading pharmaceutical companies released their trial plans for the first time on Thursday.

Those details — first published by Moderna, then by Pfizer — provide some clarity about a process that many scientists and Democrats fear is being rushed by the Trump administration ahead of the November election.

On Wednesday, President Donald Trump challenged CDC Director Robert Redfield’s estimate that a vaccine rollout could happen by summer 2021, calling that timeline a “mistake.” Trump said a shot could be available as early as October.

The documents from Moderna and Pfizer reveal that that projection is far too optimistic. They suggest that the trials may need to run through at least the end of the year to determine whether their vaccines are safe and effective.

Prior to Thursday, none of the nine companies in late-stage trials had released the blueprints for their studies. Another high-profile trial, led by AstraZeneca and the University of Oxford, was put on hold last week after a serious safety concern was raised; it was then restarted in the UK, South Africa, and Brazil, but not the US, with little explanation about either decision. (An AstraZeneca spokesperson said Thursday afternoon that the company planned to publish its protocol soon.)

Polls indicate that the public’s willingness to take an eventual vaccine is waning, and scientists have called on manufacturers to disclose more about their processes. In releasing its blueprints, Pfizer, which is developing its vaccine with the German company BioNTech, said it “recognizes that the COVID-19 pandemic is a unique circumstance and the need for transparency is clear.”

“Today is a momentous day, as it turns out, for transparency in the vaccine trials,” Eric Topol, a clinical trial expert at the Scripps Research Translational Institute, told BuzzFeed News. “If anything deviates from this, that’s when you get particularly worried.”

But Topol is already worried that Moderna’s — and especially Pfizer’s — main criteria for judging whether the vaccine works are too lenient. For example, Pfizer plans to include mild COVID-19 cases, which it defines as having one symptom, such as a sore throat or a cough. Topol said evidence of the vaccine’s efficacy would be more compelling if the threshold were raised to more severe cases, such as hospitalizations.

If the vaccine is being compared to a lot of cases where people are not that sick, “that doesn’t tell you if the vaccine is really doing its job,” Topol said. “The whole intention here is to block people from getting really sick.”

Moderna’s protocol, as first reported by the New York Times, suggests that analysis of the vaccine data would not begin until December at earliest, with more solid conclusions projected by spring 2021. Pfizer’s blueprint suggests a six-month timeline to complete its trial, but the first of four interim assessments to see whether its vaccine is at least 30% effective — or a failure — would happen after its first 32 volunteers test positive for COVID-19. Under the protocol’s assumption that 1.3% of volunteers in the placebo group will get sick, that would take about five weeks from the time the last volunteer is enrolled. The FDA is requiring that coronavirus vaccines be at least 50% effective.

Last weekend, Pfizer announced it planned to enroll a total of 44,000 volunteers and hoped to finish enrolling its first 30,000 this week, and that conclusive data may be available as early as October. But the protocol suggests that estimate is optimistic. Even if enrollment finishes this month, the earliest time for its first patient assessment would happen in late November, given the time needed between its two shots, and another week that is needed to develop antibodies to the virus.

The company has previously said it hopes to manufacture and distribute 1.2 billion doses of the vaccine by the end of 2021.

Topol expressed concern about Pfizer’s four planned interim assessments, which he said was unheard of in clinical trials. (A more typical number is two, Topol said, which is the number that Moderna plans to do.) Building in so many opportunities to potentially end the trial midway through, rather than waiting until the end, increases the risk that the vaccine’s apparent effect at whatever given moment is a fluke.

“Rule number one in clinical trials is don’t stop them midstream,” Topol said. “You interrupt an experiment, you’re very likely to get a false reading of efficacy.”

According to David Benkeser, a biostatistician at Emory University, both protocols are standard designs for late-stage vaccine trials. But, he said, given the circumstances of the pandemic, “We may be justified in feeling a bit discomforted” if a vaccine reaches the threshold of 30% effectiveness in an interim analysis, the benchmark in Pfizer's trial.

If only that data is used, it would be difficult to answer more specific questions about what other measures people should take to protect themselves, how long the vaccine’s protection might last, or how effective it is in young people versus older adults, he said.

A Pfizer spokesperson said that if efficacy is reached during an interim analysis, the study would not immediately stop. The company would consult with its external, independent data-monitoring committee and regulators, the representative said.

Operation Warp Speed — a Trump administration partnership between the Department of Health and Human Services, the Defense Department, and vaccine makers — has invested around $10 billion to fast-track the development and distribution of coronavirus vaccines. The head of the effort, Moncef Slaoui, told Science magazine this month that he would step down from his position in the event of political pressure to rush out a vaccine.

And last week, nine pharmaceutical executives, including the CEOs of Moderna and Pfizer, signed a pledge to abide by “high ethical standards” and “only submit for approval or emergency use authorization after demonstrating safety and efficacy through a Phase 3 clinical study.”

Regardless, a Pew Research Center poll this week found that the number of Americans who said they would not get a coronavirus vaccine has increased from 27% in May to 49% in September.

“I’m worried that we could lose a very promising COVID-19 vaccine for reasons that have nothing to do with the science, or whether or not the vaccine works or is safe, but because of perception,” said Peter Hotez, a virologist at Baylor College of Medicine, in an interview before Moderna and Pfizer posted their plans. “Operation Warp Speed urgently needs to get ahead of this. So far they’re not doing it.”

Both the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines rely on genetic material called RNA injected into patients to stimulate an immune response to the “spike” protein unique to SARS-CoV-2, a novel approach that promises more rapid production than traditional vaccines. AstraZeneca’s vaccine relies on a weakened version of a common cold virus equipped with this same spike genetic material to alert the immune system to the virus that causes COVID-19. Neither approach has yet led to an approved vaccine.

UPDATE

This story has been updated with comments from Emory University biostatician David Benkeser.

UPDATE

This story has been updated to include a comment from a Pfizer spokesperson.