Sheathed in yellow-green skin and stuffed with buttery flesh, the Carla is a good-looking avocado. But its heft is what makes it legendary — and valuable. At 5 inches long and 2-plus pounds, the Carla puts your average Hass to shame.

So apparently lucrative is the Carla that it’s sparked a legal battle in Florida, where its patent holder, the company Aiosa, is suing a rival for allegedly selling illegal clones.

Aiosa, whose full name is Agroindustria Ocoeña, has a US patent for the Carla tree until 2024. But for years, unauthorized Carla clones have been popping up in supermarkets, Aiosa alleges. It is accusing the distributor Fresh Directions International of violating its patent and illegally growing the clones, which Fresh Directions denies.

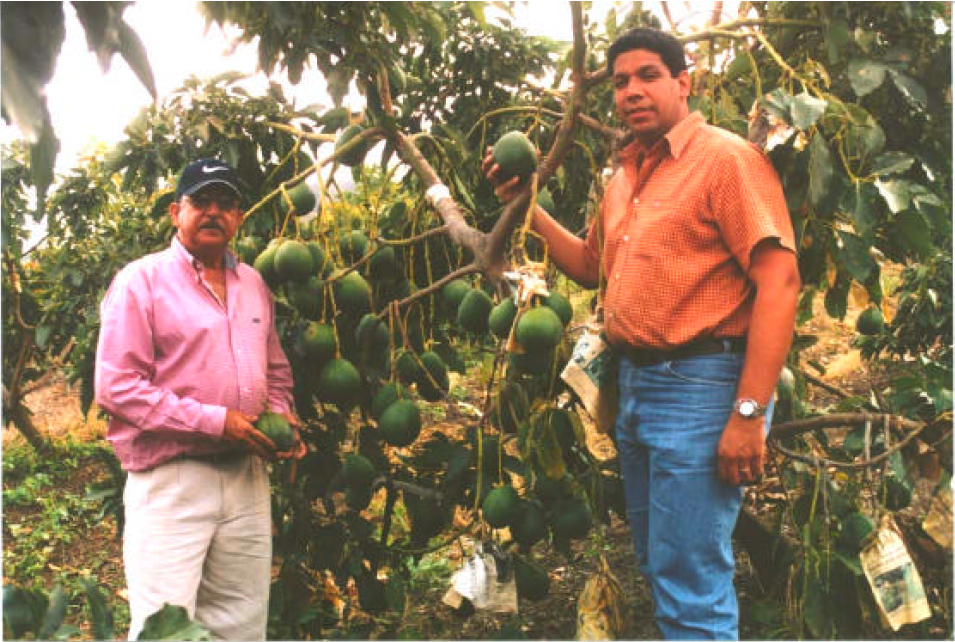

On its family-run farm in the Dominican Republic, Aiosa grows tropical fruits like mangoes and coconuts plus several varieties of avocados. But the Carla, it says, is its “star,” with 4.5 million produced every year. Fresh Directions’ patent infringement allows it “to reap a substantial unfair commercial and competitive advantage,” Aiosa argued in the lawsuit filed this fall.

In case you haven’t gone to brunch in the last decade, the so-called superfood is a full-blown health obsession. Its creamy, fatty goodness, once relegated mostly to guacamole and ceviche, now fills smoothies, sandwiches, salads, soup, and, curiously, popsicles and pie. Millennials prefer to slather the stuff on toast (instead of buying houses). The average American gobbles down 7 pounds of avocados a year, double what they did in 2007.

All of which means the avocado biz is seeing green. Every year, the US imports $2.6 billion worth of avocados from countries that increasingly include the Dominican Republic, one of the world’s top growers.

“People want to live longer, stay younger, look prettier, healthy, and anything you can come up with — any crop or anything like that that has these properties and nutrients and can do anything — that is what consumers are looking for, functional food so to speak,” Edward “Gilly” Evans, an agricultural economist and director of the University of Florida’s Tropical Research and Education Center, told BuzzFeed News. “Avocados fall smack in that.”

Enter the Carla. In 1994, Carlos Antonio Castillo Pimentel, who’d founded Aiosa 12 years earlier, discovered the fruit growing on a single tree in his orchard, located in the Ocoa River valley in south-central Dominican Republic. “Had the new variety not been discovered and preserved it would have been lost to mankind,” Pimentel wrote in his patent application, filed in 2004.

As he went on to explain, the Carla is unlike other avocados — and not just because it’s not a Hass, the dark-green, thick-skinned variety that dominates an estimated 95% of the US market. Most of those are grown year-round in Mexico and imported into the US.

In contrast, the Carla is a West Indian or green-skin avocado, which is grown in Florida and the Dominican Republic and known for its smooth, bright-green covering. Its harvest season typically runs into March. But the Carla can be harvested for even longer — from February into May, June, or July when kept in cold storage. Because it’s available when avocados are in short supply in Florida, the Carla can charge more.

“If you can keep yourself in the market longer and you have a late variety, then you maintain your position in the market, and you can sell fruit,” said Jonathan Crane, a tropical fruit specialist at the University of Florida. “So Carla is a late variety that the Dominican Republic avocado industry purposely is growing to enter that late, late market.”

That’s not the Carla’s only asset: Its flesh also manages to stay fresh for up to eight hours after being cut open, so eaters can save it for later.

And yes, it’s enormous. In 2016, when it went on sale at British retailer Marks & Spencer, the Daily Mail marveled at its girth (“the giant ‘Carla’ avocado that is FIVE times bigger and weighs 1kg”) and the Metro declared it “terrifying”: “It looks like a mango. It is not a mango.”

It’s not unheard of for companies to patent new crops for the right to sell them exclusively for several years. Agricultural behemoths such as Monsanto have been heavily criticized for such patents, but smaller outfits do it too. Acosta Farms in Miami, for instance, has patented three avocado varieties: the Lali, the Victor, and the Nico.

This practice has both upsides and downsides for the agriculture industry, said Alan Chambers, a tropical fruit breeder at the University of Florida: “My personal feeling is that whatever someone has created, they should have the right to be compensated for it.”

Avocados have tempted criminal minds before. Thieves have plundered thousands of dollars’ worth of fruit from orchards in New Zealand and distribution centers in Southern California.

Growing your own stolen avocado fruit is a different matter. It’s not as straightforward as planting a Carla seed in the ground, since, due to how avocados grow, the resulting tree wouldn’t produce a Carla avocado. But it is easy, so long as you get the tree’s buds. “You can literally drive by a tree, walk into a grove, cut off a few branches, and now you’ve got it,” Crane said.

A thief would then join, or “graft,” the branch with budding Carla fruit to a different avocado tree in the early stages of growth, experts said. As the two merged together, the top of the new tree would produce Carla avocados.

In 2012, Aiosa staffers began noticing that Carla lookalikes were being shipped into the US via Miami. That August, the company’s lawyer, Ury Fischer, fired off a stern warning to Fresh Directions that the fruit’s DNA matched that of the Carla’s. At the time, Aiosa didn’t intend to sue and wanted “to first attempt to resolve this matter amicably” by charging a retroactive fee to license the patent, Fischer wrote in his letter, which was made public in court filings.

That didn’t happen. In September, Aiosa filed its lawsuit in the Southern District of Florida against Fresh Directions, a California company with operations in Miami.

According to the lawsuit, Fresh Directions was selling Carla clones as recently as February of this year. The reportedly illicit fruit carried the “AVOPRO” trademark on a sticker (Fresh Directions also does business under the name Avocados Plus) and the label “Produce of Dominican Republic.”

As part of their detective work, Aiosa’s lawyers went shopping in Miami supermarkets. Before long, their office was filled with dozens of avocados. “We ended up eating a lot of guacamole,” Fischer told the Miami Herald.

When they once again tested the DNA of these Carla lookalikes, the lawyers found that the fruits had genes “identical” to the patented variety, according to the lawsuit. The trees on which the clones grew, Aiosa concluded, must have been illegally reproduced from the patented tree.

Fresh Directions does admit to importing and selling Carlas in the US — but denies that doing so infringed on Aiosa’s patent. In court filings, it argues that the patent is invalid, and that Aiosa is trying to enforce it “in a way that exceeds the scope of the grant of the patent.”

Court documents don’t explain how Fresh Directions would have originally gotten its hands on a Carla tree, and attorneys for Fresh Directions did not return requests for comment.

But family connections may have played a role. A former agriculture minister for the Dominican Republic told the BBC that Carlos Antonio Castillo Pimentel, the tree’s discoverer, at one point gave his brother, Manuel, some of the tree’s buds. (Fischer, Aiosa’s lawyer, told BuzzFeed News he was not aware of this story until he read the BBC article and has never seen evidence of it, so cannot confirm its veracity.) Whatever happened, the two brothers ultimately went separate ways in business: Carlos, who has since died, created Aiosa, and Manuel is the head of a company that owns Fresh Directions.

The feuding companies’ dispute over the Carla may soon come to an end. This month, attorneys for both companies set a date for mediation in March, when they’ll try to come to an agreement. ●