Silicon Valley startups are racing to develop a blood test for cancer that many scientists believe is years, if not decades, away.

It’s a high-stakes competition, fueled by hundreds of millions of dollars in venture capital. The winner could help millions of patients fight off cancer before the disease shows any outward symptoms — early enough to drastically improve their odds of survival.

Or at least that’s what these companies envision on their websites and pitch decks, and at scientific meetings — and investors are buying it.

Founded in 2014, Freenome raised $65 million last month from Andreessen Horowitz, Peter Thiel’s Founders Fund, and Alphabet’s venture arm GV. One of Freenome’s most prominent rivals, Grail, which spun out of the DNA-sequencing monolith Illumina in 2016, has raised an eye-popping $1 billion from the likes of Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos. Another competitor, Guardant Health, has amassed close to $200 million.

So far, however, these companies have shared scant few details about how, exactly, they’re creating a test that could fundamentally change how we deal with cancer.

Freenome’s CEO and cofounder, Gabriel Otte, told Fast Company in April 2016 that its test would hit the market within nine months, after being published in a scientific journal. In June, he wrote a blog post claiming that those results would appear “very soon.” That hasn’t happened. Otte told BuzzFeed News his staff is still setting up clinical trials and will publish results “when we’re ready to publish.” (Otte recently admitted to BuzzFeed News that he does not have a PhD, despite multiple references to the contrary in the press, company materials, and scientific conferences.)

Grail and Guardant have not published any findings, either, although their executives also say they intend to.

Academic cancer researchers, meanwhile, say producing this kind of test is an incredibly difficult scientific and logistical challenge. Nascent tumors sometimes shed telltale markers in the blood, but often don’t, and these “biomarkers” can be different from one person to another, or even in one person from one month to the next. Plus, credible data will take at least several more years to accumulate in rigorous clinical trials, if not longer.

“It’s not going to be a Star Trek, ‘let’s take a quick sample and tell you exactly what disease you have and how to treat it,’” Jeremy Jones, an assistant professor of cancer biology at the City of Hope in Los Angeles, told BuzzFeed News.

There’s no question that such a test would be revolutionary.

There’s no question that such a test would be revolutionary, giving its inventors enormous social and financial rewards.

“Early detection is incredibly attractive, because if you can detect cancers early, you can cure them at a much higher frequency,” Tony Blau, a hematologist who directs the Center for Cancer Innovation at the University of Washington, told BuzzFeed News.

Just as investors in Theranos, the $9 billion startup now fighting for its life after very public regulatory missteps, envisioned a world where doctors could test for all kinds of conditions from a few drops of blood, Silicon Valley is embracing the vision of cancer screening for everyone, early and often.

Blood tests for early-stage cancer would be drastically better than current diagnostic methods like “tissue biopsies,” in which doctors extract potentially cancerous tissue with needles and surgeries. Tests on a couple teaspoons of blood could be much less expensive and invasive, and performed more often. A highly accurate test would also have an advantage over today’s non-invasive tests. Mammograms, for instance, have high rates of both false negatives (they miss one in five breast cancers) and false positives (which happen to about half of women who get the test annually over a decade).

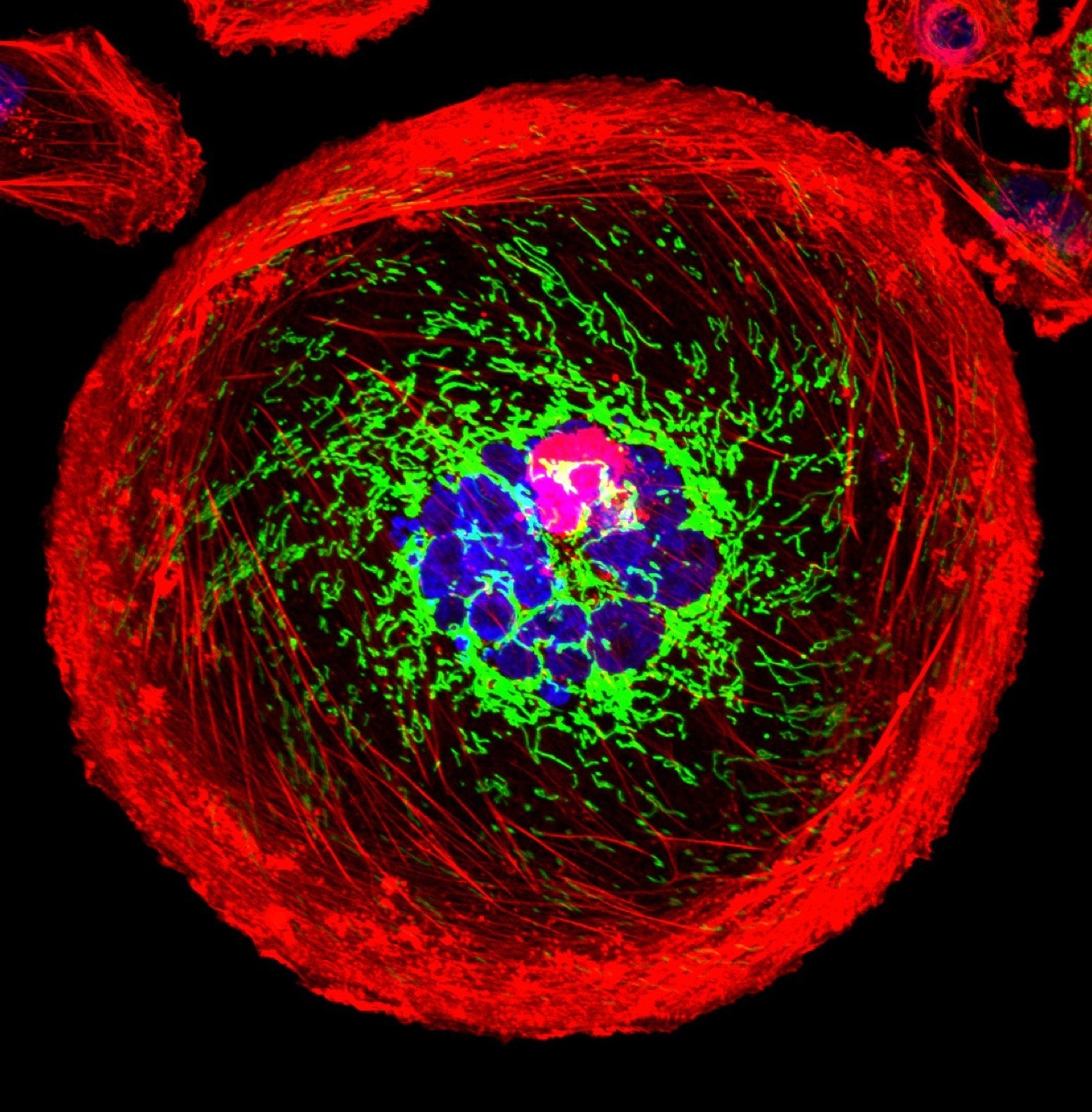

Scientists have long known that cancer cells routinely shed bits of DNA into the bloodstream. But in the past few years, thanks to advances in DNA sequencing, these bits have become far easier to detect.

There are already a handful of tests, led by Guardant, that use these DNA bits to detect cancer in a cancer patient’s blood, or to identify certain mutations that might be treatable with personalized therapies.

But so far, there is no reliably accurate commercial test that can do this for people who are early in the disease and have not yet been diagnosed — the lofty goal of Freenome and its competitors.

The DNA shed by early-stage tumors accounts for less than one-tenth of a percent of all DNA in a patient’s blood, said Ash Alizadeh, a Stanford University oncologist who helped develop and sell a technology to potentially help doctors monitor how a tumor responds to therapy. For some tumors, such as those that start in the brain, their DNA is virtually undetectable even in tens of milliliters of blood, he added.

“The concentrations are so low,” Alizadeh said. “That’s been a major challenge for early detection.”

Even if a test was able to detect every single molecule of DNA in a blood sample, that wouldn’t be enough. Machines often generate false-positive readings of clumps of cells that are deceptively cancer-like, such as moles that don’t turn into melanoma or colorectal polyps that don’t become colon cancer, Alizadeh says.

“Do we know that those changes are always going to lead to a cancer that could threaten a patient’s life?” said Blau of the University of Washington. “The answer to that is no, we don’t know that.”

Yet another hurdle is simply knowing what DNA sequences to look for, since, as Blau points out, cancer cells differ within the same patient, and even within the same tumor.

And even if a test appears to work in a lab, proving it works in people will take years. “You have to test thousands of patients, wait long enough that enough of them get cancer and enough of them ultimately die of the disease, to be able to really evaluate if a new test is a useful screening test,” Max Diehn, an assistant professor of radiation oncology at Stanford, told BuzzFeed News. (He also consults for Roche, which owns the technology he co-developed with Alizadeh.)

One of Grail’s first steps is a multi-center clinical trial in the United States with at least 7,000 patients with untreated cancer, and 3,000 cancer-free people. It began in August 2016 and plans to wrap up by August 2022.

Scientists hope to understand the molecular differences in the two groups’ blood samples, as well as how they change as disease develops. Grail has an advantage in its ties to Illumina, the world’s dominant supplier of DNA-sequencing machines, which expects Grail to become “one of Illumina’s largest customers over time.”

“Our hope is over time that we’ll be marching the population back earlier and earlier to where almost everyone who has cancer is diagnosed early,” Grail Chief Business Officer Ken Drazan told BuzzFeed News.

Guardant, on the other hand, believes that the knowledge it has already gleaned from testing 35,000 cancer samples can help pinpoint how the disease arises. President AmirAli Talasaz says that in addition to studying tumor DNA fragments, the company is looking at other kinds of chemical changes in tumors, called “epigenomic” variations. Guardant is running clinical trials of various sizes, including on high-risk patients and cancer survivors; a spokeswoman said there is no estimated date of completion.

Meanwhile, Freenome is testing its technology on patient blood samples from UC San Francisco, UC San Diego, Massachusetts General Hospital, and other clinics. For some samples, Freenome tries to predict if the patients received a cancer diagnosis or not. Other samples are from patients who are still being tracked for cancer but haven’t yet been diagnosed. In total, Freenome plans to test “thousands” of samples, though Otte declined to say how many have been tested to date. He still contends that these data will be published in a scientific journal before tests are sold commercially.

The CEO reportedly hooked Freenome’s main investor, Andreessen Horowitz, after acing a blinded test of five blood samples provided by the venture capital firm (which also invests in BuzzFeed). As Otte wrote last year, the company correctly categorized two of the samples as normal, and the other three as cancerous — and even accurately labeled what stage of disease. Although two of the cancer samples were from patients in late stages, he wrote, the third was stage one, a sign that the test could detect early cancer in a healthy-looking person.

At a conference in San Francisco in February, Otte shared some striking numbers with an audience of scientists. Freenome had an accuracy rate of more than 95% in detecting the presence or absence of prostate cancer in 351 samples, according to an abstract of the presentation that Otte subsequently confirmed was real.

Supposing that Freenome’s test is as sensitive and specific as the rate claimed, “that would be a surprising result,” Diehn, of Stanford, said.

Alizadeh said there doesn’t seem to be enough information about the studies to know what to make of the technology’s apparently high performance. “For any test, especially a clinical one,” he said by email, “interpreting accuracy requires knowing the error rate.”

In Diehn’s view, too, there isn’t enough information to evaluate Freenome’s claims. “When you have a surprising result, the onus is on the scientists to provide evidence — strong evidence, supportive evidence — for such a claim.”

During his presentation, Otte also said Freenome had a 97% average accuracy rate in detecting breast, prostate, lung, and colorectal cancers across four stages of progression, including stage one. The sample size wasn’t disclosed.

“If they’re trying to say they can tell what stage a patient has, based on a blood test, I would find that would be very surprising,” Diehn said.

A stage is defined by how far a tumor has spread from where it started, which usually requires imaging and pathological tests, according to Diehn. Sometimes, he said, the only difference between a stage-one and stage-two tumor is being slightly bigger, or spreading to a single lymph node.

According to Jones, who attended the presentation, Otte said that Freenome could tell when a case of prostate cancer was aggressive or low-risk. There are “early indications” that the technology can do this, Otte told BuzzFeed News, but it is still in development.

Otte acknowledged that all of these results need to be validated in larger clinical trials. “We’re focused on making sure that we get the numbers we need to prove to the world that our tests are safe and function well.”

“What they’re saying could be they’ve developed a great test, or they don’t really have the data, and they’re trying to make it sound like they have.”

Otte’s talk left Jones impressed, he said, but wondering, “How do we know it’s real?” He understands why Freenome wouldn’t want to reveal its technology’s nitty-gritty to competitors before the test is on the market. But that choice, he said, “makes it difficult in academic science to know how valid it is.”

Diehn put it more bluntly: “What they’re saying could be they’ve developed a great test, or they don’t really have the data, and they’re trying to make it sound like they have.”

Freenome’s test picks up not only tumor DNA fragments, Otte said, but DNA changes that signal “how the immune system is responding to the presence or absence of the tumor.” Freenome’s machine-learning platform deduced that a stronger-than-expected link between these unspecified immunological signatures and cancer, Otte said.

It makes sense that the immune system would respond to an abnormal growth early on, Jones says. But “the immune system obviously responds to things other than cancer all the time,” he added. “What if a patient is on antibiotics, what if they have an active viral or bacterial infection? Does that cloud the ability to detect the cancer pattern?”

Unlike Guardant and Grail, Freenome does not have a clinical or scientific advisory board. The company is in the process of building them, Otte wrote last month.

Vijay Pande, a general partner at Andreessen Horowitz and a Freenome board member, said the company is rightfully broadening its analysis beyond just tumor DNA. “There’s a whole landscape, in principle, of what’s going on in your body available in blood,” he told BuzzFeed News.

There aren’t existing papers that describe the basis of Freenome’s approach, Pande acknowledged — but that’s because its computational methods are so advanced, they’re effectively creating new knowledge. “This is new territory,” said the former Stanford computational biologist. “This could not be done 20 years ago.”

Whether it can be done today remains to be seen.

CORRECTION

Ash Alizadeh said that the concentrations, not computations, of some tumor DNA in the blood is very low.