Of the more than 600,000 Americans who have died of COVID-19, a disproportionate number are Black. Growing research suggests that a key to understanding why lies in examining where many of them spent their final days: in the hospital.

A new study published on Thursday, and believed to be the largest of its kind so far, finds that for Black patients hospitalized with the coronavirus, the quality of the hospitals they are admitted to may play an outsize role in determining whether they survive. Hospitals mattered more than any other individual traits like age, income, or other medical conditions.

The study, published in JAMA Network Open, comes after a brutal year in which the coronavirus pandemic and a reinvigorated civil rights movement collided to highlight racial and economic disparities in healthcare. While the virus killed fewer people in white, wealthy enclaves, it crushed communities of color with low incomes — and the chronically underfunded, effectively segregated hospitals that served them. Black people account for about one-third of COVID-19 deaths in the US, even though they make up only about 13% of the population.

“It’s not surprising that Black patients may live [near] and therefore go to hospitals that have fewer financial resources and therefore have a harder time providing optimal care,” David Asch, a University of Pennsylvania professor of medicine who led the study, told BuzzFeed News. “There are a variety of elements of our historical past that have tended to create white neighborhoods and Black neighborhoods, rich neighborhoods and poor neighborhoods. This is the legacy of our nation’s racial history.”

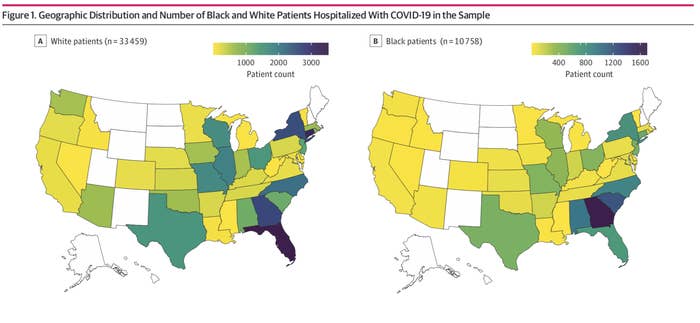

Asch’s team looked at Medicare Advantage data for more than 44,000 patients who were admitted with COVID-19 to a total of nearly 1,200 hospitals across the US from January through September of last year. And they looked at the number of people who died, measured by either dying at the hospital or being sent to hospice for end-of-life care within a month of hospital admission.

In their analysis, the researchers accounted for differences in other traits — like age, gender, income, and non-COVID-19 medical conditions — between the groups of Black and white patients who died. Even when the other factors were equivalent, Black patients were more likely to die.

Their increased odds of dying didn’t seem to be rooted in health differences, such as the chronic conditions like diabetes and heart disease seen in high numbers among Black patients. Instead of individual factors, the most direct link to who ended up dying was where they were hospitalized. Black patients were on average more likely to be admitted to hospitals where patients of all races died at higher rates, the analysis found. In contrast, white patients tended to check into hospitals where survival rates were higher overall.

Black and white survival rates might basically level out, the researchers calculated, if Black patients received care in the same hospitals and in the same distribution as white patients.

“There are of course many reasons why Black patients often have worse outcomes than white patients. But often one of the reasons is that Black patients, for a variety of reasons, find themselves going to hospitals that have worse outcomes for all,” Asch said.

Asch stressed that the study doesn’t single-handedly prove that the hospital that a Black patient checks into is the determining factor in whether they live or die. It also left open the possibility that the difference could be driven by circumstances even bigger than the hospitals themselves — the states in which people got hospitalized. The study acknowledged that it was unable to disentangle one from the other, since Black patients were distributed differently than white patients across states.

But his team’s finding does track with what is already known about the relationship between how segregated hospitals are and the quality of care people of color receive for other conditions, said Amal Trivedi, a professor at Brown University School of Public Health who was not involved in the study, by email.

It’s a dynamic that predates the pandemic. Black patients are more likely than white patients to undergo surgery at low-quality hospitals in segregated areas. They’re more likely to be under-treated for, and to die from, pneumonia at hospitals that primarily serve Black patients, compared to white patients at mainly white-serving hospitals.

The reasons for these differences date back to even earlier in history — to the Jim Crow era and its aftermath. When Black families were legally excluded from buying homes in the suburbs and denied conventional mortgage loans, they were unable to build up generational wealth and were effectively forced into racially segregated neighborhoods. And when inner-city neighborhoods grew predominantly Black, their hospitals closed in greater proportions than those in white neighborhoods.

Many of the hospitals that still serve minority communities with low incomes were already hanging by a thread when COVID-19 hit. On Chicago’s South Side, where about 1 in 5 residents live below the poverty line, Roseland Community Hospital quickly became maxed out when the virus struck last spring. “We are outgunned, outmanned, underfunded, and no one is coming to help us,” the head of the hospital told the Chicago Tribune in April 2020. When South Los Angeles erupted into a COVID-19 hot spot over the winter, sick patients flooded the 131-bed Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital. “The hospital is surrounded by a sea of chronic illness and lack of access to healthcare,” the CEO told the Guardian.

In some places in the US, there wasn’t even a hospital to turn to. A record 19 rural hospitals shut down in 2020, disproportionately cutting off healthcare access for Black communities in the South and Southeast while COVID-19 cases and deaths surged.

The quality of hospitals also likely affected patient care in the lead-up to the pandemic, setting people up for worse outcomes, said Ruqaiijah Yearby, a law professor who specializes in racial disparities in healthcare at Saint Louis University School of Law. “This is probably some place they were going for all of their care, that left them without the proper care, and so they were more vulnerable to dying from COVID-19,” she said.

Earlier studies examining racial disparities among COVID-19 deaths in hospitals have been based on smaller data sets from one or a handful of healthcare systems. The largest study until now was based on data from more than 11,000 patients across 92 Catholic hospitals in the Ascension network, a large, private healthcare system. Researchers there reached a similar conclusion to the study published Thursday, though phrased it differently: When they controlled for the hospitals where patients went, Black COVID-19 patients had basically the same chances of survival as their white counterparts.

But experts are still puzzling over which characteristics of a hospital, exactly, might be making the biggest differences. Perhaps it’s having a certain volume of COVID-19 cases, the number and training of healthcare staff, or access to key equipment like ventilators. Baligh Yehia, a senior vice president at Ascension, said he’s attempting to tease out these granular factors in forthcoming research.

“‘What is it about the hospital?’ is the next question,” Yehia said.

The new study also did not examine whether, within hospitals themselves, Black and white COVID-19 patients might be treated differently by staff and if those differences affect their health. For most other health conditions, both of these scenarios matter, noted Karen Joynt Maddox, codirector of the Center for Health Economics and Policy at Washington University in St. Louis. “Black patients typically have worse outcomes even within the same hospital, AND Black patients typically receive care at lower-quality hospitals, so worse outcomes are due to BOTH things,” she said by email.

Throughout the pandemic, Black patients have raised concerns that they are not taken seriously — sometimes with fatal results, as in the case of Susan Moore, a Black doctor who was hospitalized with COVID-19 at an Indiana University hospital late last year. In a viral Facebook video, Moore complained that her white doctors were ignoring her pain and failing to treat her appropriately. After she died, an investigation concluded that while the medical care she received didn’t contribute to her death, Moore did suffer at the hands of providers who “lacked empathy, compassion and awareness of implicit racial bias.” The hospital system has apologized for its failures and pledged to increase its diversity and equity training.

And not everyone who is killed by COVID-19 dies at the hospital. To understand why Black Americans are dying in greater numbers, researchers say there is a need to explore why many Black Americans may not feel comfortable going to a hospital in the first place and may instead be dying, for example, at home.

“It’s not just about ensuring hospitals in a predominantly Black neighborhood are of high quality,” Yearby said. “It’s about ensuring it’s a place where those patients want to go, feel comfortable going, and that they receive the highest quality of care in those places.”