More than 5 million Americans won't be allowed to vote in the 2020 election, one of the most consequential in recent history, because of a felony conviction, according to a new study released Wednesday.

The Sentencing Project study shows that, despite reforms to laws in many states over the past 25 years, felony disenfranchisement is still alive and well in the US.

"There's been a lot of state activity in order to challenge felony disenfranchisement ... but even in spite of that there is so much that needs to be done," Nicole D. Porter, director of advocacy at the Sentencing Project, told BuzzFeed News. "Because mass incarceration is a problem ... the number of people disenfranchised is still too high for a country that wants to be considered a model of democracy."

The report from the nonprofit criminal justice advocacy group, titled "Locked Out 2020," estimates that 5.17 million people are barred from voting this year because of a felony conviction — down about 15% from an estimate of 6.11 million disenfranchised Americans in 2016.

According to the study, felony disenfranchisement continues to be more prevalent in states in the South, where voting restrictions have historically been used to exclude Black Americans from the electorate. For example, in Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, and Tennessee, more than 7% of adults are still unable to vote because of felony convictions.

Nationally, the disenfranchisement disproportionately affects Black people and other communities of color. According to the study, 1 in 16 Black Americans and 1 in 49 Latinx Americans who are of voting age are not allowed to vote; among non-Black adults, that figure is 1 in 59.

In Florida, despite a 2018 constitutional amendment overwhelmingly approved by voters that restored voting rights to about 1.4 million former felons, nearly 900,000 people who have completed their sentences are still barred from voting, the study estimated. That's because of a law passed by the state's Republican-controlled legislature and signed by Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis last year that made restoration contingent on paying outstanding restitution, fines, and fees related to their convictions.

Former felons sued the state over the law arguing that it creates a “pay to vote” system akin to the poll taxes outlawed under the US Constitution. But a federal appeals court upheld that 2019 law in a 6–4 decision on Sept. 11.

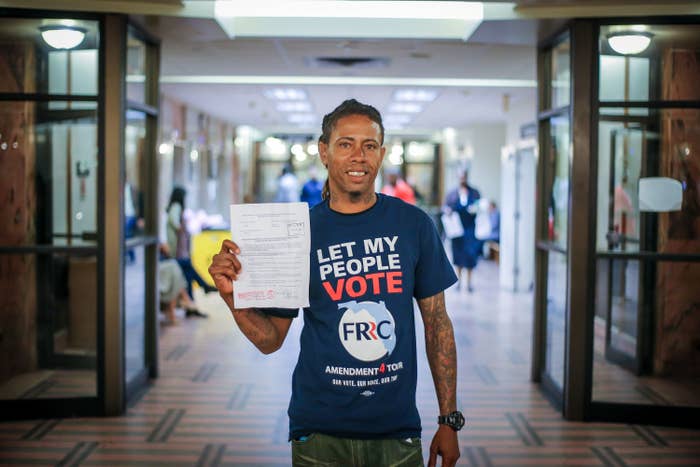

In response to the state law, the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, the group behind the 2018 amendment, created a "Fines and Fees Fund" and began working with court clerks in all 67 counties to help former felons figure out and pay off their financial obligations or modify their sentences, as allowed under the state law. The coalition started paying people's fines in late 2019 and has since received more than $27 million in donations from over 86,000 people for the fund — a large portion of which flowed in after the court decision last month.

"We’re doing what we can to remove financial obstacles for people who are too poor to be able to pay off those legal financial obligations," the coalition's executive director, Desmond Meade, told BuzzFeed News in a recent phone interview.

Porter with the Sentencing Project noted that the group's estimate predates the Sept. 11 ruling, saying, "there is no doubt a lower number of people who are currently disenfranchised compared to when we generated our estimate of close to 900,000." At the time of the court decision, the coalition said it had helped more than 4,000 former felons through its program. (Representatives for the coalition did not immediately respond to requests for an updated figure Wednesday.)

It's difficult to say how many Floridians with prior felony convictions have registered to vote because the state does not have a database of former felons who have paid off their fines and fees, according to University of Florida political science professor Dan Smith, who has studied the impact of the law. There is also no central system showing what people owe, making it difficult for former felons to figure out whether they have any outstanding financial obligations.

"That is still a problem," said Meade. "That's why the work that we’re doing, working with officials to really try to sift through that, is just so important, so vital."

Even Meade, who has spent nearly a decade advocating for returning citizens, only became aware earlier this year through his latest petition for clemency that he still owed $1,200. When he inquired about his outstanding financial obligations years ago, he said, he was told he had paid off his debts.

"I was able to afford to pay it, but it just shows how complex this system is. And if a person like me ... [has] something like this happen, then, well, what does that mean for the average citizen?"

For 45-year-old Dolce Bastien, who was convicted of a felony in the 1990s, the coalition's work made all that easy. After it helped him work through the courts to ensure all of his financial obligations were taken care of late last year, he plans to vote for the first time in his life this fall.

"I'm excited about it," said Bastien, who works at a Family Dollar store in Jacksonville.

He told BuzzFeed News being barred from voting after completing his sentence and turning his life around felt like "a continuous punishment."

"Not being able to vote just is another way of feeling that you’re no longer connected with our society," Bastien said. "Now, to be able to feel like I can make a difference ... makes me feel good. The magnitude of the feeling that I am going to have when I actually show up at the poll and vote is going to be overwhelming."

The Sentencing Project's Porter said that while what happened in Florida "is in many ways a cautionary tale," the passage of that state's constitutional amendment, which was considered the largest restoration of voting rights in history, is part of a growing effort.

In the last couple years, several states — including Iowa, Kentucky, and New Jersey, — have restored voting rights to more categories of former felons. In California, voters are currently considering a proposition that would allow former prisoners to vote while on parole.

"The solution around this is to continue to challenge felony disenfranchisement ... and really to work towards no loss of voting rights for any resident with a justice involvement," Porter said. "We still have way too many people who are locked out of voting."