A federal judge on Friday said she will appoint an independent monitor to investigate the treatment of children in immigration detention facilities in Texas as the Trump administration struggles to reunify hundreds of children still separated from their parents.

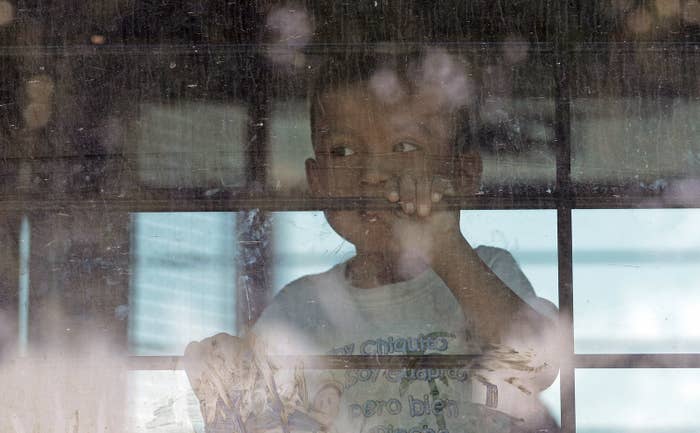

US District Judge Dolly Gee said at a hearing in Los Angeles that due to continued reports about children not getting adequate food or having access to drinking water, as well as living in unsanitary conditions, she needed a special monitor to give her an objective view of what’s happening on the ground.

Gee said the monitor will provide reports to the court to ensure compliance with her previous orders issued in the Flores case.

“It seems like there continue to be persistent problems that are contrary to the orders that I have issued,” Gee said.

The monitor will be chosen in a matter of weeks and ensure compliance with a 1997 settlement, known as the Flores agreement, that restricts how long children can be held in immigration detention and sets standards for how those children should be treated and cared for.

Peter Schey, president of the Center for Human Rights and Constitutional Law, which is representing immigrants detained at the border, said the monitor will have jurisdiction over two Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) family detention centers in Texas and one in Pennsylvania, as well as US Customs and Border Protection facilities in the Rio Grand Valley.

Schey said that in addition to the inhumane treatment described by immigrant parents and children detained at the border, the government has failed to comply with parts of the Flores agreement that require the prompt release of children to a relative or family friend when possible.

The Flores agreement requires the government to place immigrant children taken into custody at the border in a nonsecure, licensed facility, ruling out long-term detention. The government has interpreted the settlement and subsequent rulings in the case to mean that children cannot be held in immigration detention for more than 20 days.

Earlier this month, Gee rejected the Trump administration’s request to change the terms of the Flores agreement to allow the Department of Homeland Security to detain families for as long as their cases are pending.

An attorney representing the Department of Justice, one of the defendants in the case, argued that before appointing a monitor the court should hold a hearing to determine whether the government had violated the agreement.

But Gee said that wasn’t necessary because her previous orders found the government not to be in compliance.

“I’ve already made a finding of breach,” she said.

The plaintiffs had argued for the monitor to oversee all border patrol facilities where children are being held, saying that the poor conditions — specifically children being held for days with no access to potable water, inadequate and expired food, and no blankets or sleeping mats — were pervasive across facilities along the border.

Gee said that it was unrealistic for a single monitor to cover that much ground, adding that her June 2017 order to grant a previous motion from the plaintiffs to enforce the Flores agreement were specific to facilities in the Rio Grande area.

“We’re hopeful that by having a special monitor to observe border patrol facilities and operations in Texas, we’re hoping that that adds a salutary effect on border patrol operations throughout the southern border,” Schey said.