The Supreme Court on Wednesday delved into the meaning and purpose of Andy Warhol’s iconic portraits of Prince as they considered whether the artist violated the copyright of the photographer who took the 1981 picture he used to create his work.

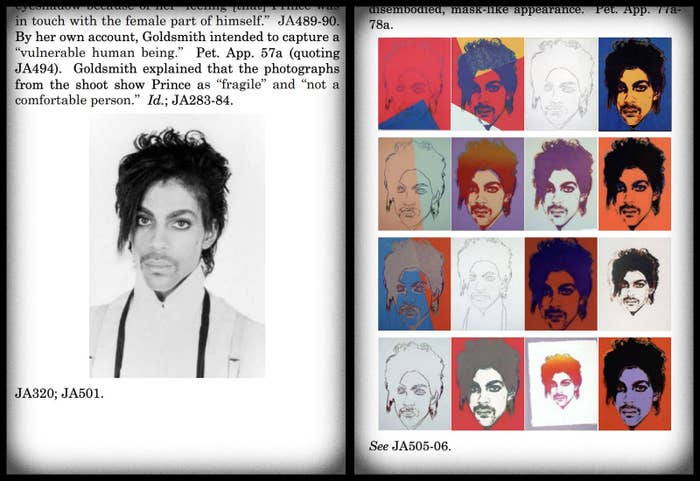

Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc., v. Lynn Goldsmith stems from the foundation’s licensing of one of Warhol’s prints to Vanity Fair for a commemorative issue about Prince following his death in 2016. After seeing the magazine cover with the print depicting the musician’s face and the backdrop in an orange tint, Goldsmith, who is best known for her portraits of rock icons, was sure the image infringed her copyright. Decades before, she’d licensed her black-and-white photo of Prince to Vanity Fair so it could provide the image to Warhol as a reference to create an illustration for a 1984 issue. But she never knew that Warhol created 15 other silkscreen paintings, prints, and drawings of Prince based on her original photograph.

The central question of the case has been whether Warhol needed Goldsmith’s permission, which he wouldn’t have if his works fell under fair use, a legal doctrine that aims to protect freedom of expression in criticism, news reporting, and other areas. An appeals court previously ruled in Goldsmith’s favor, and now the matter is in the Supreme Court’s hands.

In a lively hearing peppered with references to Lord of the Rings, TV shows, the "Mona Lisa," and Justice Clarence Thomas’s taste in music, the justices seemed dismissive of a lower court’s holding that judges shouldn’t try to "ascertain the intent behind or meaning of the works at issue” when trying to determine the purpose and character of a work — something that’s part of the fair use test. But it was unclear whether they believed the foundation’s argument that the Warhol prints substantially transformed the meaning of the original photograph was strong enough to outweigh the copyright claim.

Roman Martinez, an attorney for the foundation, argued that the market for the two works is different because their “aesthetics” and licensing prices are different, as are the meanings behind each of them. Warhol’s prints were meant to be about “the dehumanizing effects of celebrity as applied to Prince,” Martinez said, while Goldsmith captured “a photorealistic portrait of Prince that showed him as fragile and vulnerable.”

“There’s no real dispute in this case that the meaning or message of the two works were different,” Martinez told the court. “The only real question in this case is whether that difference matters.”

In their questioning, justices tried to pin down the degree of transformation that would qualify as fair use as they asked hypothetical questions about adding a smile to Prince’s face, plastering the words “Go Orange” to Warhol’s print, or even changing the color of the dress in Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa.

“If you showed those two to most people today, they would say, 'Well, all right, brown dress, blue dress, red dress, doesn't make any difference, right?'” Justice Samuel Alito said. “But, if you called somebody who knows something about Renaissance art, the person would say that makes a big difference. If that's a blue dress, that's sending a message. If it's a red dress, that's sending a different message.”

At another point during the hearing, Thomas began asking rhetorically about whether using Warhol’s orange print of Prince on a poster at a Syracuse University sporting event would qualify as fair use.

“Let’s say that I’m both a Prince fan, which I was in the ’80s and—,” Thomas said.

“No longer?” Justice Elena Kagan said, sparking laughter in the courtroom.

Thomas went on to argue that if he added the words “Go Orange” to the image that he’d changed its message.

Whatever the justices decide could have big implications. Warhol’s foundation as well as other artists and museums have argued that upholding the lower court’s ruling could limit artists creatively and threaten the ability of museums, collectors, and galleries to display, sell, or even possess work that borrows from or refers to copyrighted material — a practice that has been a defining feature of art throughout history.

“Art thrives on freedom and the ability to put your work out there for others to see and respond to,” Thomas Crow, a professor of modern art at the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University, told BuzzFeed News. “If everybody feels they’ve got to consult a lawyer before they execute an idea, it can't be good.”

Crow, who provided an expert report for the foundation in its original case discussing the differences between Warhol’s work and Goldsmith’s photograph, said stealing another artist’s work is obviously wrong — but that’s not what happened here.

“If you put Warhol’s Prince portraits and Lynn Goldsmith’s photograph next to each other, it would take you a while to figure out that the one came from the other,” Crow said. “They’re not the same.”

But Goldsmith, other photographers, and even the Motion Picture Association — which represents major studios in Hollywood — have argued that applying the foundation’s definition of what makes new work “transformative” would give copycats free rein to infringe on copyright, whether that's using an unlicensed photo or producing a spinoff or sequel of a movie without permission.

“Petitioner argues adding new meaning is a good enough reason to copy for free,” Goldsmith’s attorney Lisa Blatt argued during Wednesday’s hearing. “But that test would decimate the art of photography by destroying the incentive to create the art in the first place, and it's obvious why the multibillion-dollar industries of movies, music, and publishing are horrified.”

The potential ramifications for not just the art world but also the entertainment industry seemed to be front of mind for the justices as they considered the arguments.

“So, if a work is derivative, like Lord of the Rings, you know, book to movie, is your answer just like, well, sure, that's a new meaning or message, it's transformative, so all that matters is [factor] four [of the fair use doctrine]?” Justice Amy Coney Barrett asked Martinez, the foundation’s attorney.

Martinez started to say that he didn’t think that the two had “a fundamentally different meaning or message” but then said he’d probably have to catch up on the differences between the books and the movie series before giving a concrete answer.

“You need to do a very careful analysis of new meaning or message, and it's really going to be only in the cases that there really fundamentally is a new meaning or message that are going to be able to sort of satisfy that first factor,” Martinez said.

Erica Van Loon, an intellectual property trial attorney who focuses on trademark and copyright issues, told BuzzFeed News that instead of ruling on whether Warhol’s work is fair use, the Supreme Court could instead come up with a more refined test to determine whether a work is transformative and send the case back to the lower court to apply it.

Van Loon pointed out that while questioning Yaira Dubin, the assistant to the solicitor general, who argued on behalf of the US Copyright Office in support of Goldsmith, the justices seemed interested in her argument that the Warhol foundation must show “that copying the Goldsmith photograph's creative elements was essential to accomplish a distinct purpose.”

During their questioning, multiple justices pressed Dubin to nail down the specific language she would use to evaluate a work’s purpose and meaning.

“So the exact words we use on that question in the opinion, if we were to agree with your side, will undoubtedly be the subject of a lot of debate,” Justice Brett Kavanaugh said, “so I want to get it exactly right.”