AMMAN, Jordan — Samira Ismail doesn't want to sell her young daughter into a marriage with a man she had never met, but she can't see any other way for her family to survive.

Earlier this week, she found herself in the awful position of trying to marry her 17-year-old daughter off to a much older man who had offered to pay her family up to $3,000, money that could keep Ismail's small family afloat for nearly a year.

Like many Syrian refugees, Ismail once dreamed of lavish weddings for each of her four daughters. In Syria they would have married in the spring, she said, when the days are long but not too hot. She would have invited the entire village, and made sure that three types of meat were served. Her daughters would have borrowed her aunt's antique lace veil, and worn gold bracelets on their arms.

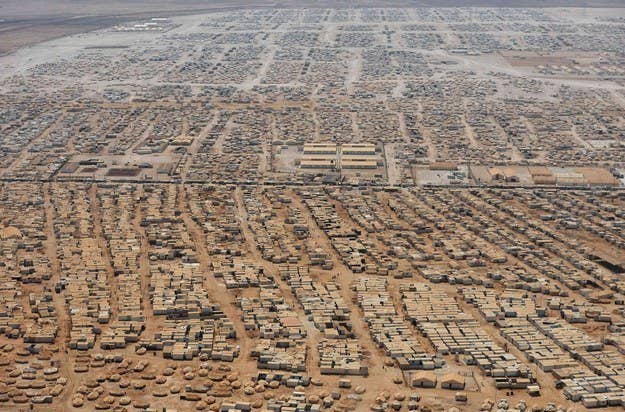

But that all changed when Samira was forced to flee her village near the southern city of Homs as the violence that has claimed more than 160,000 lives intensified. Eighteen months ago, she arrived in the Zaatari refugee camp, where she lived in a tent for four months before moving to an already crowded apartment near the Jordanian city of Ramthe. The men in her family try to find odd jobs to make ends meet, but they almost always come up short.

There are more than one million Syrian refugees in Jordan, and like them, Samira and her family are left to watch helplessly as violence continues to rage at home. They are increasingly aware they may never return home. This left them with no choice, she said, but to marry off one of her daughters.

"No mother wants this," said Ismail. "But this is our life now."

She was sitting in the grubby apartment of a well-known broker of Syrian brides in Amman, who only agreed to speak to BuzzFeed so long as she could use the pseudonym Dima. She isn't proud of the work she does, but Dima's ties to several families in the Gulf mean she can set up prospective grooms with Syrian brides.

It was not long before one of the several phones on Dima's desk rang. On the other end was the cousin of a prospective groom. He had been tasked, he said, with finding an appropriate wife.

"[The men] all want the same thing. They want blue or green eyes, very pale skin, and very young," said Dima. "Very, very young. That is what they all say."

Dima's phone call lasted for just a few minutes and was conducted in brisk, clipped sentences. They agreed to meet in person in a café in one of Amman's more upscale neighborhoods. Dima carried nothing but a phone with photos of the prospective brides. As she left Dima told Ismail she must prepare herself.

"If he chooses your daughter it will happen quickly. If he says he will marry her, I will ask you to send for your daughter. Have her wear something pretty, but modest. He will take her this month and transfer the money to you," said Dima. "God bless her."

She said that girls as young as 13 have been married off by their families, though most brides range from 15–17. The conflict in Syria has already forced many young Syrians to grow up faster than their parents would have wanted. At an age when most teens are discovering their first crush, or preparing for university, young Syrian women are considered at their prime marrying age.

The grooms can be anything from 40 to 70 years old. They largely come from the oil-rich Gulf countries to buy a Syrian bride, paying dowries ranging from $300 to $3,000. Syrian women have long been prized in the Arab world, where their pale skin and light-colored eyes are admired. Before the violence in Syria began, families could at least vet potential grooms to ensure their daughters would be well treated. Today, they say, they are lucky if the marriage lasts more than a few months, before the groom tires of the girl and sends her back to her family.

NGOs and human rights groups in Jordan say that no one knows how many of these marriages take place. Sewar Sawlha, PR director of Save the Children, said that while Save the Children's protection unit does what it can to try and educate families about the disadvantages of early marriage, many still take place.

"They have no money, a lot of these young girls, these teenage girls, and they tend to see these marriages as a solution to their problems," said Sawlha.

Only a small handful file legal marriage certificates with the courts, in most cases the bride and groom simply visit a local mosque, where a short ceremony takes place. It makes it easier for the groom, they say, to send the bride back once he is done with her.

"In many cases these marriages do not last. But I have no control over this, I am just the matchmaker," said Dima. Some have compared what she does to misyar, or short-term marriages that are practiced in some Gulf countries, and Egypt. Those marriages allow the husband and wife to live separately, and for the husband to carry no financial responsibility for his wife, according to the rules established by the Egyptian Sheikh Sayyed Tantawi in February 1999. Dima, however, insists that her couplings have every chance to end in happy matrimony.

"These girls have the opportunity to marry men who will take care of them, take care of their families. Is that not better than living in the dust of a desert refugee camp or dying in Syria," she said. "I am helping them through these marriages."

In Amman, the meeting between Dima and the Saudi family takes less than 30 minutes. Two male cousins of the groom and a friend of the family ask few questions outside of the age and location of the girls. In other cases, the family has asked Dima to take them to the Zaatari refugee camp to view the girls for themselves. But in this case, they appear to make due with photos.

Several brides are discounted for being "too old" and one is too full-figured. Ismail's daughter is one of a few picked out as potential contenders, but the Saudi family needs more time to decide.

"These are all very good girls, they come from very good families," Dima told the family, whose surname she would not reveal. She seemed disappointed that they have not made a decision. For each match she makes, she receives a commission of nearly $300.

In the end, Ismail and her family have to wait less than 24 hours before receiving a phone call from Dima. The Saudi family decided to go with another girl. At 17, Ismail's daughter was considered too old.

"God willing, I will find another husband for your daughter," Dima told the family. There are Jordanian men also looking for brides, she said, if Ismail is willing to consider them.