IRBID, Jordan — Raghad remembers the last time she felt like a normal teenage girl — two years ago, when she was sitting in front of her computer at home in the southern Syrian city of Daraa.

Now, she finds herself in a clinic for women and girls in northern Jordan, worried she won't remember her Facebook password or Skype login. Friends she used to chat with daily are scattered from Lebanon and Jordan to internal displacement camps inside Syria. She knows that some are now injured, or possibly dead. In Syria, Raghad was about to graduate high school, and begin a degree in computer science. Now she is one of nearly 1.3 million Syrians who have fled her country's civil war for Jordan.

"All I want is to be able to get back on a computer. To feel normal again, like I am pursuing a normal life," said Raghad, who, like all of the Syrian women who spoke to BuzzFeed at the clinic, asked that she be quoted using only a first name.

Eighteen-year-old Raghad is one of dozens to seek shelter at the Irbid Women's Center, which offers psychological counseling, babysitting, and classes in everything from basic banking, including how to use an ATM, to learning about finance and wages.

"To be a refugee, especially a female refugee, is to be vulnerable to a very different type of trauma and violence than other people," said Nawal Mohammed, the head of the clinic, which is financed by the International Rescue Committee. "Whether they are with their husbands or widows, these women have to look after themselves in a way most of them never had to in Syria."

As the fighting in Syria enters its fourth year, some of its worst violence has been directed at women. Inside the country, women speak of the ever-present fear of rape, while outside, upon becoming refugees they find themselves attacked by their husbands, fathers, and brothers for whom domestic violence has become an all-too-common means by which they can vent their anger.

The issue of sexual violence against women remains taboo and is rarely discussed among Syrian refugees. Mohammed says many of those who visit her center have shared those stories, sometimes from new arrivals, other times from women who have been visiting for months or even years.

"For too many women the violence continues when they are refugees," Mohammed said. Physical abuse at the hands of their husbands is common, especially as months and years pass by with the situation in Syria as intractable as ever. "Men sometimes take out their frustrations on their wives. They feel helpless as refugees so they beat their wives."

Mohammed is sympathetic to her clients' struggles, having fled the West Bank city of Nablus with her family during the 1967 war.

"I know what it's like to be a refugee, to blend into this mass of people who no longer have a home, a nationality that defines them," she said.

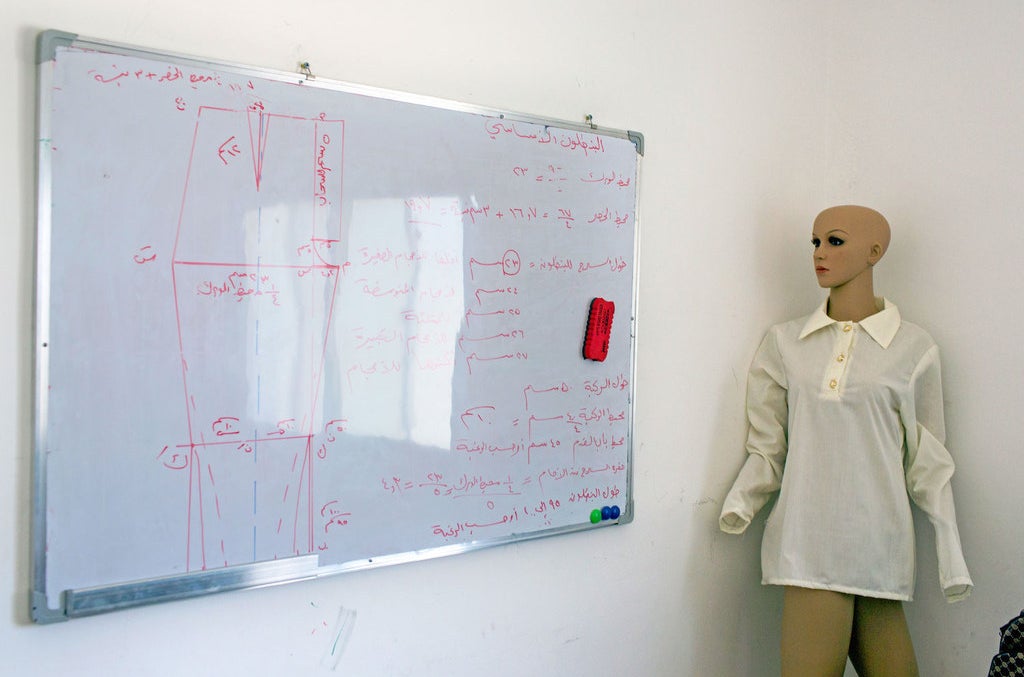

So she aims to provide refuge at her clinic. On a recent afternoon, a group of eight women gathered for a sewing class in one room, joking about adding rhinestones and lace to the simple patterns with which they were working. Next door, a woman named Um Ahmed was sewing a new curtain for her home using a luminescent pink material that was once a young girl's dress.

"I have no husband, now I can decide on the color of the curtain and I wanted pink," she said. "I make all the decisions now."

Then there was Mai, a 46-year-old mother of four who attends weekly "beauty hours" at the clinic. "I had not put on makeup in one year, I had not done my hair," she said. "When I went home, I felt like a woman again for the first time in a very long time."

"It is nice to be frivolous, when we have had nothing frivolous in our lives for so many years," Mai said. "I don't feel like Mai the refugee, but Mai the woman."

Jordan's government has complained that it does not have the resources to indefinitely host the 1.3 million Syrians already in the country. They are just a fraction of the estimated 9 million who have been displaced internally and externally in Syria in the past three years, 2.5 million of whom have fled to its immediate neighbors, including Turkey and Lebanon. Water, food, and shelter are already running short. In many periphery towns, where employment was already scarce, the presence of Syrians eager to work for even a meager daily wage has led to racism and discrimination against the refugees.

"Many of the women still talk about returning to Syria during our group counseling sessions," said Mohammed. "But more and more they talk about what life would be like if they stayed in Jordan. They are preparing themselves for that possibility."

Rana, a 37-year-old woman who lost her husband and child in a bomb strike last year, said, "It will not be easy to make new homes here, but more and more of us think this is what we must do." She fled to Jordan with her two surviving children. "I am trying to make a new life for them here."

Raghad, the teenager who so wanted to study computer science, has had considerable difficulty adjusting to life away from Syria.

"Mostly, I just sit at home," she said. "I feel sad, so I just sit, very still. I do very little. Sometimes for days I can sit at home, until I can't stand it anymore, and then I force myself to do something."

She said she missed her computer, and the promise it once held: "I have not touched a computer since we left Syria. It has been so long, I am afraid I will never be able to work on a computer again." Without skipping a beat, Mohammed jumped in. "You can work on the receptionist's computer," she said. "It's important for you to leave the house and continue your studies."

Raghad could barely speak. She spent the next few minutes staring at the computer before the receptionist, also from the Syrian city of Daraa, told her to come sit at the desk.

It was the first time Raghad had felt like herself since becoming a refugee.