Ahmed Tawfiq props two laptops on the desk in front of him and scrolls through his Facebook feed. It's Friday morning, which his sister jokingly refers to as "protest day," and the two are looking for their marching orders.

"This is the first thing I do, before I drink tea, before I eat or wash I look to see what is being said by our members on Facebook," said Tawfiq, a 23-year-old who helps his local University chapter of the Muslim Brotherhood. "This is how we communicate these days."

Quickly, he spots a Facebook status that calls for Brotherhood supporters to gather in the Nasr City area of Cairo for a march; the exact details and time would be released in the coming hours.

"See, I click here and I share it and then my sister sees it and shares it and that is our chain. This is how we organize everything today — like this at the last minute," he said, clicking through several Facebook pages associated with the Brotherhood and the broader "Anti-Coup Movement" they protest under. Within seconds, a protest could move from one gathering point to another, he said, or a new chant be circulated ahead of a march.

Barely a week passes in Egypt, without a newspaper publishing an article declaring the end of the Muslim Brotherhood. With most of its top leadership in jail, the hierarchy of the Brotherhood has been thrown into disarray.

"The Brotherhood has always relied on its hierarchy to make decisions, and has a very strict chain of command that alerts the supporters to every action, every protest," said Abd Galil al-Sharnouby, a journalist who formerly edited the Muslim Brotherhood's online news site. "Now they are having to change this system, they must rely more on online presence."

The move to posting orders online is an effort to try to create a more flexible system, one that can withstand the deaths and arrests of Brotherhood members and supporters.

"They have created an alternative person for every position, so that if one is arrested another one can step in," said Sharnouby. "But keeping the communication open is more difficult. For that they have had to rely more on going online."

But relying on open, online sites can be risky for the Muslim Brotherhood, as they pay elaborate cat-and-mouse games with the police.

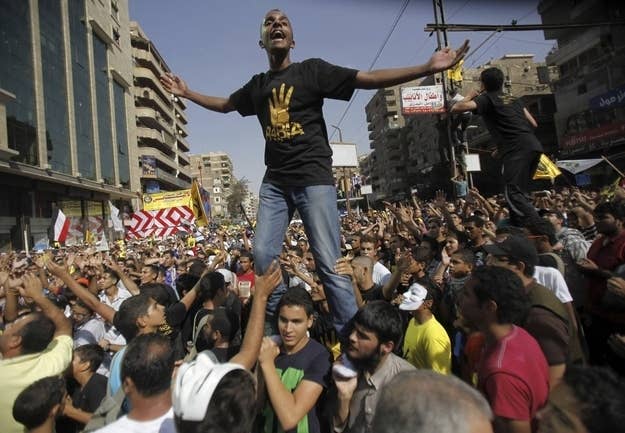

Tawfiq boasted that the Brotherhood could organize protests and rally sites faster than the police could deploy to stop them — but in reality, the police have arrested hundreds of Brotherhood members and are expected to put them on trial. Last week, Egypt's Ministry of Social Solidarity announced it was dissolving the Muslim Brotherhood as a government-approved NGO. Earlier, a Cairo court announced a ban on all Brotherhood activities and seized funds from the group.

Still, Brotherhood supporters have marched every Friday of the month.

"This is the most important thing, that every week we gather and march," said Tawfiq, who over the last three months has seen four friends arrested and a cousin killed during the protests. "We will never stop our protests, not until the rightful government is replaced, not until [former Egyptian President and Brotherhood leader Mohamed] Morsi is released."

Members of the Brotherhood say as long as they can get online and issue a rallying cry, their supporters will answer.

"By continuing to go to the streets, to organize and to be active, we are showing that we still have a right to defend our legitimacy," said Yomna Muhammed, a 21-year-old university student. "Me and my friends, we are always online looking for the next event."

The Brotherhood has always used Facebook, Twitter, and other online forums to organize their supporters and spread messages. Sharnouby said the group saw the importance of the internet as early as 1999, when its top leaders issued an edict that all Brotherhood members should learn basic internet skills and be active online.

"The internet has always been important, but now it is even more so," Sharnouby said. "Before they could pass messages through a variety of methods, through appearing in media or through phone chains, now they have to rely on the internet."

Sharnouby said that the Brotherhood leaders who have evaded arrest confer with the top leadership outside the country and with mid-level members remaining in Egypt to make a decision on what sort of centralized messages to spread online.

"As long as we have the internet, they can't wipe us out," said Rasha Abu Ilil, a 36-year-old mother of two who helps organize a local Brotherhood chapter in the Cairo suburb of Nasr City. "It is not like in the past, when they could jail the leaders and the movement hid at home, afraid, and not knowing what to do."

Former Egyptian President Gamal Abd al-Nasser was able to persecute the Brotherhood, jailing and torturing them, because no one knew how to organize the movement's support base without the leadership's help, she said.

"This time we will not wait home, we will not go quietly. We have Facebook, Twitter, and our own sites," said Ilil. "They would have to shut down the whole internet to shut us down."

But organizing a message and disseminating it online is not always easy, especially amid growing fears that even mid-level members of the Brotherhood are being arrested.

On Friday, Tawfiq and his sister were preparing to leave for a protest when a message suddenly popped up on Facebook, calling on all Brotherhood members to avoid marching toward Tahrir Square, the well-known site of the 2011 Egyptian uprisings that has remained a focus of protest movements.

Just moments earlier, Tawfiq's sister had been boasting that the group would fill Tahrir Square and refuse to leave until all the Brotherhood members were released from jail.

"This is good, this is the right thing," Tawfiq abruptly said. "We do not need to march on Tahrir, there are other places more important."

The important thing was that the public saw them not as a threat, but as a friend, he said.

"We will continue to march until all of Egypt supports us," he said, adding that he was not afraid of arrest. "At least now they know that they cannot silence us."