From the stands, Jay Mullen didn’t like what he saw. He didn’t like that the Soviet basketball team was humiliating its overmatched Ugandan opponents. He didn’t like that the visitors were bigger, stronger, faster, and more skilled than the amateurish Ugandan army and prison guard teams. He didn’t like that the Soviets were outscoring, out-rebounding, and out-everythinging the home team, and didn’t like that they were throwing the ball off the backboard and dunking it. They were putting on a Harlem Globetrotters–type show and the Ugandans were the Generals.

The Soviets had arrived in Kampala a few days earlier, and now they were showing why they had come: to dominate. Winning these two initial games by more than 60 points apiece, they displayed the skills that made them the best team in the Soviet Union and in Europe. They were also showing, Mullen thought, a complete lack of respect and humility. Next, they would be playing Mullen’s team, the best Uganda had to offer. As he watched the Soviets pummel the locals, it made Mullen want to retaliate, to wound the visiting team’s estimable pride, and to regain it for the Ugandans. And if he could serve his own country at the same time, then so be it. That idea, he liked.

In 1972, in the middle of the Cold War, the Soviet military sent a team of all-stars to Kampala to compete in three goodwill basketball games against Uganda’s top players. The Soviets, who were hoping to curry favor with the leader of the new regime, Idi Amin, didn’t know that the best of the three squads, the Ugandan national team, was at that time being coached by an American named Jay Mullen. And they definitely didn’t know that Mullen was an undercover CIA operative, sent to Uganda earlier that year to spy on the Soviets.

The space race was winding down, but the nuclear arms race was accelerating at a perilous rate despite talks of limitations. U.S.-backed coups were happening all over the world. Courting and deposing regional leaders was a global game being played by dangerous men. At a moment when any shift in the balance of power could lead to Cold War escalation between the USSR and U.S., the team from the USSR had been invited by the Ugandan Ministry of Defence as a way to show solidarity between the militaries of this East African country and the Eastern Bloc.

A coup supported by the CIA was partially responsible for the series of events that led to this athletic standoff — an uncelebrated moment in the annals of Cold War sports that includes the Miracle on Ice and boycotts at the 1980 and 1984 Olympics. For decades, the Cold War was played on the field, the pitch, and the basketball court. Victories for individual athletes were seen as triumphs for superpowers, for capitalist or communist ways of life.

Mullen was the coach of the Ugandan national basketball team for six months under the reign of Idi Amin. During that short time, he would turn a team of amateurs — the first generation of Ugandan basketball players — into a proxy army against the USSR’s propaganda tour. “I’m a competitive guy and, number one, I wanted to win,” he told me. “Number two, I’m competing for the hearts and minds of the world, and if I could in some microscopic way derail this thing of theirs, I would’ve enjoyed that, and I almost felt an obligation to try.” If the Soviets were trying to impress Ugandan leaders by winning a basketball game, he would do everything in his power to make them lose.

In March, I visited Mullen in southern Oregon, where he has been living for almost 40 years. Ever since our first conversation in 2013, the tall, white-haired history professor had not stopped asking me, “Did you follow that?” — checking in as he breathlessly shared stories from his travels and how they intertwined with historical events.

At home with Mullen, I could see how he would be the right person for the CIA job. His 46-year-old son, Tobey, told me that Mullen often speaks without words, pointing at things he wants. I witnessed as much, but I also saw him initiate conversations with strangers like it was nothing, breaking the ice with at least three different people by asking if they had Nordic ancestry. At dinner one night, without warning, he broke into the New Zealand national anthem, not the last anthem he would sing during my visit. The guy can listen, schmooze, or entertain as needed.

Before I arrived, he suggested that we talk while driving to and from the coast, where we’d be dropping off his teenage granddaughter at surf camp. Mullen spent nearly the entire three-hour trip to Gold Beach explaining the genesis of World War II to his granddaughter while she sat half-listening in the backseat of my rental car. “Did you follow that?” he asked her, often, while listing the many types of people the Nazis hated.

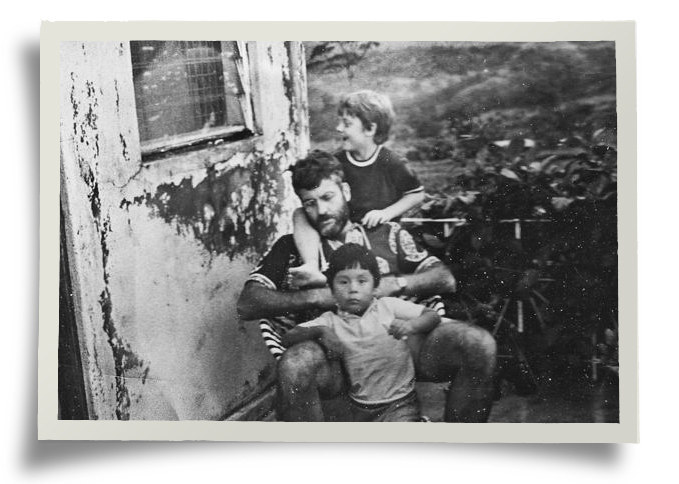

As the two of us drove back alone, Mullen began to tell me how the hell an academic originally from southeastern Missour-uh ended up taking his young family to Uganda only months after one of modern history’s most notorious dictators took power.

In 1970, Mullen and his wife, Nancy Jo, were living in Kentucky, where he was teaching history courses at Midway College. This was during the Vietnam War, which Mullen staunchly opposed and protested against. The administration at his school told him he had to shave his beard, considered a symbol of “treason” at the time, according to Mullen. “I told them to go fuck themselves,” he said. “And so I had to find a new job.”

He and Nancy Jo had also just adopted a Native American son, and then had another child who was born with severe and expensive health problems. Mullen sent form letters to all sorts of places looking for work. “I believe I have credentials that would be of interest to you,” he wrote to Xerox. “I believe I have credentials that would be of interest to you,” he wrote to the Tennessee Valley Authority. “I believe I have credentials that would be of interest to you,” he wrote to the CIA.

One night Mullen got a call from a guy who said he was with “the agency.” Mullen didn’t know if he meant the home loan agency or any of the other entities that he’d sent letters to in search of employment. As it turned out, the CIA was interested in his credentials. Then in his early thirties, Mullen was finishing up his dissertation on the influence of Indians on British colonial policy in East Africa, and he had earned a fellowship to study Wolof, a West African language, at Indiana University.

After doing a background check, the CIA asked him to come to Washington, D.C., despite his antigovernment past. “They didn’t care,” he told me. “As long as I could be inserted there and provide information, they didn’t give a goddamn if I worked for Che Guevara.” It was difficult to plausibly place operatives in African nations outside of embassy jobs, but with his academic bona fides, Mullen was fit to work under non-official cover, as a NOC.

With the approval of Nancy Jo, herself excited to try something new, Mullen joined the CIA, and, in September 1971, after an accelerated eight-week training, he and his family left for Uganda’s capital, Kampala. He would be posing as a researcher on African history; there were plenty of other Americans and Brits at Makerere University among whom Mullen could blend in. But his real job would be to get to know the Kampala-based Soviets.

At first, Mullen told me he was in Kampala as “just another set of eyes and ears” for the CIA, but he quickly corrected himself. “That’s probably a little too cute,” he admitted. “I was actually managing a ring of assets, as we called them. Some people call them a spy ring.” His assets were mostly Ugandans recruited to help gather information on the Russians living in Kampala in order to turn them into double agents. Not all of them understood what they were doing or whom they were doing it for. In the agency, Mullen said, “you recruit all kinds of people who don’t even know they’re recruited or why.”

Getting to know Russians, who were themselves trying to find Americans to spy for their side, meant going to social events once or twice a week, and drinking a whole lot. He’d meet Soviets at parties and write reports describing every detail of their mostly mundane conversations. Sometimes Nancy Jo would come along, to dance with (and gather information on) the single Russian men. The reports, along with the contents of tapped phone calls and other gathered intelligence, would be used by experts in D.C. to determine which Soviets might be willing to turn and work for the Americans. “Every one of them was a candidate,” Mullen said.

The Cold War was in full effect when Mullen arrived in Kampala. In this post-African-independence period, both the Americans and the Soviets were trying to spread their ideals to Africa, occasionally by hook and more often by crook. African leaders who showed signs, or were thought to show signs, of moving to the left — i.e., toward communism and away from capitalism — were strongly “encouraged” by American agencies to step down.

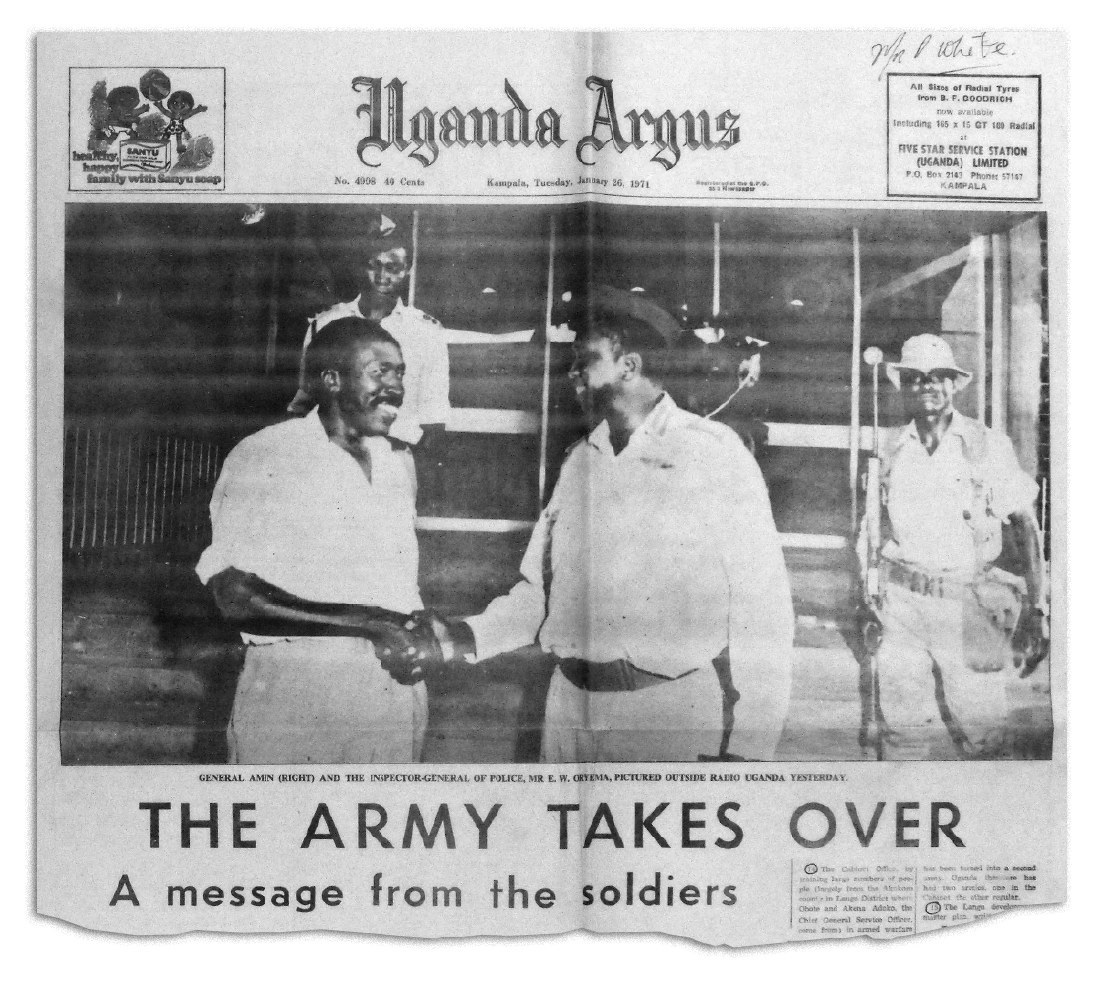

Milton Obote, the president of Uganda starting in 1966, was one such leader who made Americans wary. The CIA did not directly support the January 1971 military coup that took Obote out of power, but declassified British government documents have shown that the Israelis, and to a lesser extent the British, did, while the Americans cheered and eventually provided weapons to the new man in charge — the civilized world’s hope for Uganda, the man destined to foster under his leadership a new era of capitalist Western-style democracy, the despot known as Big Daddy: Idi Amin.

Amin’s coup happened only months before Mullen arrived in the country, and so it was under his regime that Mullen spied on the Russians. Amin had joined the King’s African Rifles, a British colonial unit, in 1946, and had trained in the U.K. and Israel. He was a big, charismatic man, a heavyweight boxing champion, and he became a Western symbol of African leadership for a short while. “Amin burst into the presidency, like Obote before him, through the barrel of a gun,” wrote historian Phares Mutibwa, “stumbling on to the pages of history.”

Amin’s reign has become famous for its brutality, but at the time of the coup it was greeted by many Ugandans with great cheer. Obote had begun physically eliminating or detaining his enemies. He’d expelled Kenyan industrial workers and used the military and police to maintain shaky yet violent control of the country. Change was welcome when Amin came to power and immediately released 55 political detainees. He spoke of halting widespread corruption, lowering taxes, holding organized elections, and stemming bloodshed. The coup was supposed to mark a new beginning for Uganda.

But Amin’s honeymoon period would not last long. As many as half a million Ugandans were killed under his regime, including hundreds, if not thousands, of prominent civil servants, academics, senior military officers, cabinet ministers, diplomats, educators, church leaders, and doctors. Anyone who posed a threat to the control of the country was eliminated. In a 1972 memo, one British ambassador described the situation in Uganda as “absolute hell.”

As the risks of being stationed in Uganda became more and more apparent, foreign governments began pulling out their personnel. The exodus from Uganda, said Mullen, was “like rats leaving a sinking ship.” One of the people who fled Kampala after the coup was the Ugandan national basketball team’s coach, a Yugoslav. With the trials for the Pan African Games — a continental version of the Olympics — coming up and a group of Soviet ballers on their way, the Ugandan team needed a new coach. Amin’s coup and the ensuing violence in Uganda had cleared the way for Mullen to step in.

When he wasn’t spying on the Soviets, Mullen spent time with his wife and kids, taught classes at Makerere University, and played outdoor basketball at the YMCA. Basketball had come to Uganda only a few years earlier, in the 1960s, through Peace Corps volunteers and missionaries. Those playing in the early 1970s were true pioneers of the sport in Uganda. Cyrus Muwanga was one of them.

“I started playing basketball probably when the first Ugandans played the game,” Muwanga, now a 66-year-old retired hand surgeon in County Durham, England, told me. As a young boy, he learned the sport from Americans who taught at his school. He and his friends would play on a grassy field or packed dirt lot.

“It was so rough, at first we thought that we’re not supposed to bounce the ball,” Muwanga said. “We’d just run.” But learning to dribble on a rough surface, which they did for two or three years before moving to a proper court, proved to be an advantage: “When you actually move to a smooth court, it’s quite easy.”

Muwanga and his schoolmates also became good shooters because they were initially playing on backboard-less netball hoops. Accuracy is key when only a swish gets you a bucket.

When Muwanga finished high school, he had to choose which college to attend for his A-levels. His father wanted him to go to the school that was the best academically. “I chose the school with a good basketball court,” Muwanga told me, following with the long, deep laugh that he attached to every basketball-related memory.

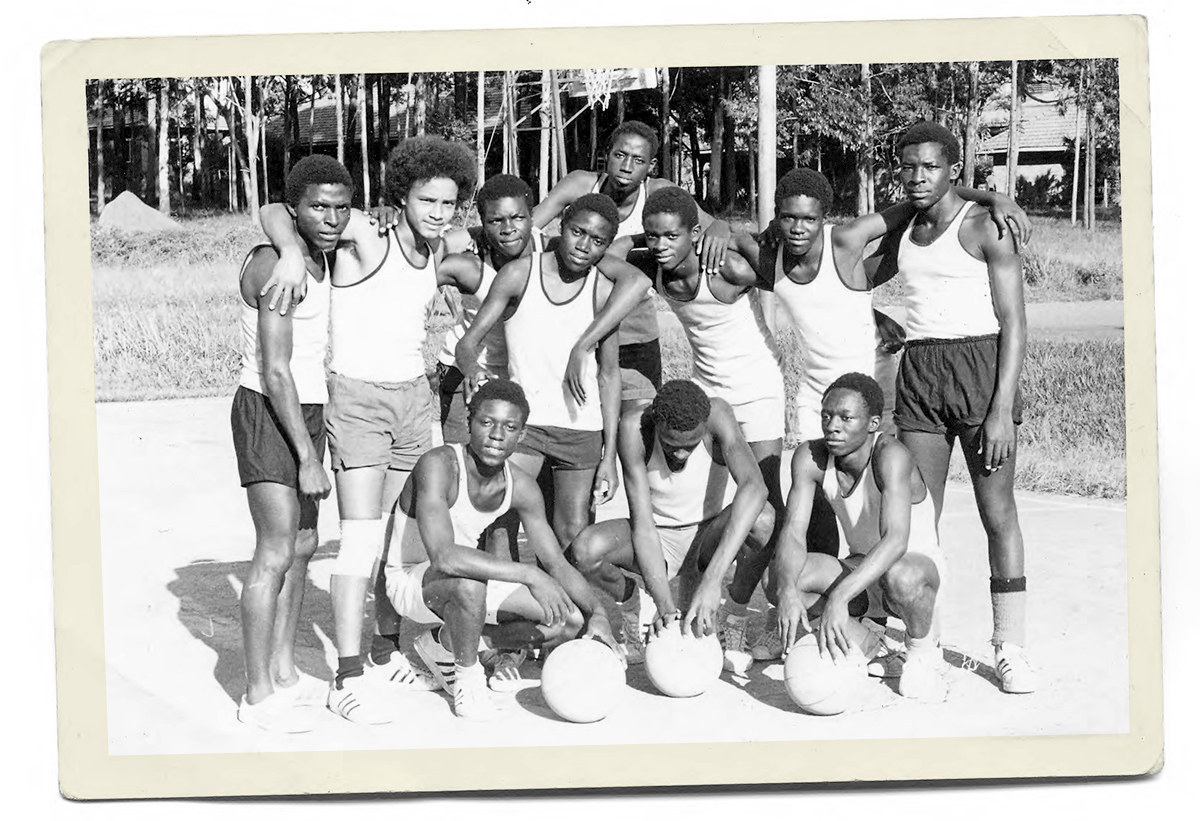

The Aga Khan School, where Muwanga took his pre-university courses, would compete against a Catholic school 15 miles down the road called St. Mary’s College Kisubi, which had three proper basketball courts. One of the St. Mary’s players was a cocky, tall drink of water named Hilary Onek.

As a younger kid, Onek had never even heard of basketball. “I didn’t know anything about it,” he told me from his office in Uganda, where he is a member of parliament. But at Kisubi, he found out about this American game where you shoot a ball through a metal hoop. His teachers singled him out for instruction because of his height. Soon, he was dominating. “I could outjump all of them,” Onek said. “I was probably the strongest player on the team.” Onek also had an older classmate named James Okwera, a great athlete and basketball star despite the fact that he didn’t start playing until he was 16. With Cyrus Muwanga holding court at Aga Khan, competitions between the schools were fierce. “When Aga Khan played Kisubi, it was a war,” Muwanga said.

“Aga Khan came second to us a lot of the time,” Okwera told me. “But they had some really good players, and my friend Cyrus was one of them, so whenever we were playing them, it was always a very tense rivalry.” In his last year at the school — during a somewhat more relaxed, if still politically unstable, pre-coup period in Uganda — the two teams played for the national school championship, with Kisubi coming away with a one-point victory. The players from both schools pushed each other to improve, and by the time they were moving on to university studies, Onek, Muwanga, Okwera, and their friends were taking the game seriously.

Muwanga and his Aga Khan schoolmate Ivan Kyeyune were Baganda; Hilary Onek and James Okwera were Acholi. At various times under Obote and Amin, members of each of their tribes were being murdered and coming into and out of power. But they say politics didn’t matter when they were on the court, and especially when they all ended up on the national team. “I don’t think that ever came across anybody’s mind,” Okwera told me. “We all trained as one, and played as one.”

In the 1970s, playing ball at the courts in Kampala in his spare time, Mullen gained a reputation as an athlete: for his pickup skills, but also because he’d been a runner at the University of Oregon, the same school as track star Steve Prefontaine. Mullen told me the reputation was undeserved, since he was a middling track athlete at best and an average basketball player. “Merely knowing how to dribble made me a hot prospect in Uganda,” he said.

As a referee for Makerere University’s intramural games, Mullen was known for his ability to handle the raucous basketball crowds. He also played in a recreational league that included men from the police and the army, along with students from the university. One of the players in the league was the head of the basketball council, James Adoa — a man who Mullen and others describe as the father of Ugandan basketball.

Playing together sparked a friendship that would lead to Mullen’s coaching gig. One day, Adoa invited him to a gathering of the basketball council at the YMCA. Adoa made announcements about scheduled games with international teams, including an exhibition game against the Russian team, meant to boost relations between the two countries. Then, to the American’s surprise, he told the council that he wanted Mullen to be the new national coach. “It was the first I heard of it,” Mullen told me. He was honored, but didn’t put much weight on the selection, at least at first. “I thought it as much a social gesture of appreciation as anything,” he said. He knew his friends from the league could use someone to set up proper offensive sets, so he accepted.

Only later would he realize his opportunity to throw a wrench in the Soviets' diplomacy-building plan.

Mullen and Adoa, who died a few years ago, had their choice of the country’s basketball talent. They scouted pickup courts at the YMCA, Makerere University, the police barracks, and even Luzira Prison, where the guards played within a barbed-wire perimeter. But the boys from Aga Khan and Kisubi had by then become men and university students, and were the country’s best players.

In this era, when the first basketball tournaments were held in the region, the Ugandans were champions in East and Central Africa. “We were beating all the teams around us,” Onek told me. “Kenya, Tanzania, Burundi, even Congo. We were running down all of them.” They won despite the fact that they were all either in school or working full-time, and could only get together on an ad hoc basis. “If there was a game, the team would be formed, and then it would dissolve until the minister of sports or someone said, 'Now we got another [opponent],'” Mullen said. “Then we’d put the team together again and practice for a while.” For the Soviet game, they went into “residential training” for about 10 days, practicing at least twice a day and sleeping at the university.

One of the team’s forwards, William Okalebo, was so talented that he had once dominated a high school game while wearing only one shoe. (Mullen, who refereed that game, would lend Okalebo his own sneakers when they faced the Soviets.) Onek was only a few inches over 6 feet, but he could jump through the roof. Cyrus Muwanga could get the ball up the court, and forward Okwera was a sharpshooter. Guard Ivan Kyeyune was as fast as anything and could outleap most players.

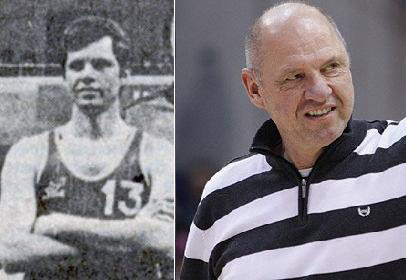

But the Ugandans faced a huge deficit in age and experience compared with their Soviet opponents. The Ugandans would be playing CSKA Moscow — one of the best teams in European history, and still a top team today. The visiting CSKA squad had won the previous four USSR League championships and two of the past four Euroleague trophies. It was an international basketball powerhouse, long affiliated with the Soviet army and a feeder for the USSR’s national team, including the one that would beat America’s best in highly controversial fashion in the Olympics weeks later. The Ugandans would be playing the 1995-96 Chicago Bulls of Europe. Neither the players nor coaches were prepared to see their opponents in the flesh.

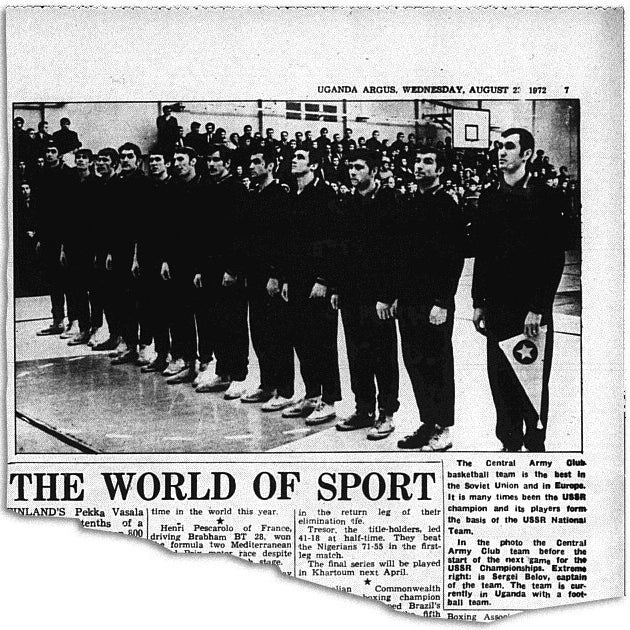

The CSKA team landed in Uganda to great fanfare on Aug. 19, 1972. Arriving with a group of Soviet ambassadors that included some of the USSR’s biggest soccer stars, the players were greeted at Entebbe Airport by representatives from the Uganda Armed Forces and the National Council of Sport. “The people of Uganda have been waiting eagerly to see them,” announced a captain from the Ministry of Defence. “You will like the way we play basketball,” the head of the Soviet athletic tour told a Ugandan reporter.

First were the warm-ups against the Ugandan prison and army teams — the blowouts that so enraged Mullen as he sat in the stands. The police and guards were roughed up and thoroughly outclassed by the Soviets, who Mullen would later describe as playing like “maulers and sadists.” “The Russians were so far superior to those two teams that they were putting on a kind of Harlem Globetrotters show and making fools out of the Ugandans,” Mullen said. Witnessing how little they cared about humiliating the Ugandan players electrified Mullen’s desire to subvert their foreign relations effort, to show that the Soviets weren’t all-powerful by beating them on the court. More importantly, he cared about his players’ pride. He didn’t want to see them torn to shreds like the other Ugandan teams.

But a similar fate felt inevitable for his own team after he saw CSKA’s Victor Petrakov, who Mullen described as “the biggest human I have ever seen.” As a spectator and fan, Mullen had seen the tallest players America and Africa had to offer. “But they were kinda gangly,” he told me. Petrakov was not gangly. He was gigantic. “He looked like the Incredible Hulk,” Mullen said. Mullen remembered the first time his team saw Petrakov — the shock, the awe, the look on Cyrus Muwanga’s face that said, We gotta try to guard that guy?

The Ugandans had to adjust their goal from beating the Russians to not getting run out of their own gym in utter embarrassment. Because their opponents played such a physical style of basketball, Mullen had to prepare his men to get pushed around. He changed the team’s routines, priming them for rough contact with bigger men than they were used to seeing on the court. He had them hit each other as they shot layups, and take vicious screens and hacks of all kinds. But practice was one thing. If Mullen’s players were going to stand a chance against the Soviet military all-stars, they would need something more than hard work. They’d need subversion. Luckily, their coach had some experience with that.

Prior to his CIA days, Mullen studied African history because he was disturbed by the racism he saw in the West. “The arguments from everybody, from the British on down,” he said, was: “‘These people can’t govern themselves because they’re inferior.’” That didn’t sit well with Mullen, so as an academic he sought to see Africa with his own eyes. But as a CIA operative, his morals were somewhat corrupted.

Mullen lied, cheated, and stole while working undercover in Uganda. He considered the Russians and Chinese adversaries, and if he could help the U.S. government get information on them, he was happy to do it. At the time, he believed that the U.S. was advocating for national self-determination in Africa and on other continents. “I thought I was on the good side,” he said. “You gotta have an intelligence agency. I don’t think there’s any question about that. I didn’t have any problems being a part of it.”

But over the course of our talks, it became clear that Mullen was torn about his own work as a spy. In Uganda, he began to see the way the CIA treated locals as disposable. “They kept telling me, ‘Don’t do anything to hazard yourself if you can get an African to do it for you.’” And for a while, that’s exactly what he did. When the CIA needed a tunnel to run wires for tapping phones, they’d hire a local, hand him a shovel, and tell him they were digging for sewer rats. That way, Mullen wouldn’t personally be at risk from Amin’s soldiers. Back then, Mullen thought of his job as sort of a game, scoring points for the agency, he said. “I did think deeper about it as time went on, and I looked back on that, and I’m ashamed.”

Mullen often worked with one particular Ugandan who had strong local connections and helped with a number of covert missions, at great risk to his own life. In addition to forging a plan to bug the Chinese Embassy and posing as a telephone repairman to tap Soviet phones, this asset also provided useful material about Ugandan governmental and military operations.

At first, Mullen said, they’d meet at his home at irregular hours, so the asset could pass on information and stolen documents. But when the Ugandan military police started parking their unmarked Volkswagen right near the house a bit too often, they changed their rendezvous to a neighborhood called Mengo, a popular area for European men to meet prostitutes. The CIA paid the rent on an apartment there, and in exchange, Mullen’s man made sure it was available when needed. To complete the cover, the asset sublet the apartment on a night-by-night basis to sex workers, making a bit of cash on the side from an apartment paid for by U.S. tax dollars. Mullen declined the offer to have a woman on hand each time they met.

As the Uganda situation deteriorated, U.S. sights gradually shifted away from the Soviets and toward Amin. “He was very predictable in that he hated imperialism, and he went after imperialist symbols,” Mullen said. Amin publicly taunted President Nixon and changed street names to honor African heroes rather than figures from the West. Many Africans, in and outside of Uganda, appreciated that, Mullen contends. “And you can do that without endorsing his thuggishness and the murders.” Phares Mutibwa mostly agreed: “Amin’s behaviour in the first few months after the coup, at least in the eyes of Ugandan civilians and the international media, was that of the man of peace,” the historian wrote. Amin, Mutibwa said, was “concerned above all with reconciliation and the securing of national unity, peace and prosperity.”

Mullen has a bit more insight into Amin than many who have written about him from afar. “I gotta be careful when I talk about this,” Mullen said. “When I met Amin, he was a warm and charming individual. That was how he related to me; I’m not saying that he was across-the-board warm and charming. I know people that lost family members at the time, and they would have found nothing warm and charming about that.”

Mullen and Nancy Jo often took their kids to a swimming pool at the International Hotel in Kampala, and Amin showed up on occasion. Mullen and his young daughter would have chicken fights with Amin in the pool, and she thought he was a lot of fun. “That’s not to say she therefore endorses the destruction of the Acholi tribe,” Mullen told me. “If he disliked you, your ass could be grass, but if he didn’t dislike you, he was capable of being a really nice guy. Can you believe that?”

Amin once challenged Mullen, along with a few other men, to a swimming race. Amin was raised in semi-arid northwest Uganda. “Hell, he grew up in the desert,” Mullen said. “He couldn’t swim worth a damn.” Amin had trouble keeping a straight line, and he veered diagonally into Mullen’s lane. Mullen didn’t notice, and he whacked Amin in the face with his backstroking hand, twice. Amin came in last, but rather than snapping at Mullen, he showed no signs of having anything but “an Aminian good time.”

If Mullen’s relationship with Big Daddy was lighthearted at the pool, it was grave behind closed doors. With the Americans quickly regretting their backing of Amin late in 1972, Mullen witnessed a potential kiss of death for his swimming mate. An agency higher-up visited Uganda, and Mullen and his chief met him in a safe house. After being apprised of the quickly escalating Idi Amin situation, the pipe-puffing CIA bigwig said, “Can’t you get rid of this guy?”

“I knew people were dying,” Mullen told me. “And I knew I could have shot the sonofabitch or stabbed him or whatever, but then, Jesus, what would have happened to my family? And then I thought, well, is my little Indian boy and my two little blonde girls worth more than a thousand African kids?” But Mullen also knew that if they were going to take out Amin, they wouldn’t send an American in, guns blazing. They’d send a Ugandan to do it.

History might have been written in that room. But before Mullen could say anything, his boss had stood up, and was pointing directly at the visitor. “You put that in writing,” he said. “You put it in writing.” The station chief wasn’t going to let this guy fly in and casually talk about assassinating one of the world’s most dangerous men.

The bigwig then said he was only kidding, of course. Amin would live to see another day, and continue to rule Uganda until 1979.

During the game’s opening ceremonies, the Ugandan army band played both the Ugandan and Russian national anthems. Ugandan cabinet members and Soviet officials shook hands with the players before retiring to the VIP section. As a gesture of togetherness, when the teams lined up, the Soviet coach pinned a hammer and sickle on Mullen’s chest, making him perhaps the only CIA operative to admit to being decorated by the Soviets during the Cold War.

Lugogo Stadium, home to the country’s lone indoor court, was the size of a large American high school gym, Mullen remembers, and shaped like an aircraft hangar, with dimly lit incandescent bulbs for the night game. Most of the country’s Russian population was in the stands, but Mullen hired a guy with a flatbed truck to bring students from the university so the crowd at Lugogo Stadium would be for the Ugandans.

The floor must have shaken as the Soviet and Ugandan fans filled the elevated tiers of seats on both sides of the maple wood court. The students trucked in by Mullen brought half a dozen drums and were banging them with all their might. “It was quite a big atmosphere,” Muwanga said.

Photographs from the game don’t seem to exist, but James Okwera remembers the crowd being in the thousands, and that, because it was early in Amin’s time, the military had a particularly big presence. Okwera also remembers being intimidated by the noise while getting ready in the locker room. “Five-thousand people would make an awful racket,” he said. “It was quite daunting.”

When the ref blew the opening whistle, Mullen was relieved to find the Red Hulk sitting on the bench. The Ugandans began the game playing way above their heads, invigorating the crowd. A gap-toothed teenager named Teso stole rebounds from the stronger Soviets. Okwera hit three jumpers in a row. The team was executing the plays Mullen and James Adoa had drawn up, and they weren’t succumbing to the Soviets’ size or strength. At the end of the first quarter, Uganda was up five points. Goddamn, thought Mullen. We might win this thing.

“It was quite embarrassing for the Russians,” Muwanga told me. “I think they thought they were just going to get a walkover, just toss us down to nothing. They hadn’t banked on the fact that, while we didn’t have the height, we had the speed and dribbling skills to outmaneuver them.”

The Ugandan team could switch from zone to man-to-man and matched up its best dribblers with the Russians’ slowest guys to take away their size advantage. “We all knew what our limitations were,” Okwera told me. “We knew we were never going to be able to properly compete with that caliber of team that was so well prepared and had all the resources they needed.”

The Ugandan lead didn’t last long. A few minutes into the second quarter, the Soviets started wearing out the locals, and Ugandan politics may have played a part. Both the referees were Pakistani, and Mullen suspected they might have had a bias against his team due to the infamous act Amin had just carried out against the local Asian community. Earlier that month, Amin had announced that all non-citizen Asians would have to leave the country in 90 days.

There were roughly 80,000 to 100,000 Asians living in Uganda at the time, many of them descendants of Indians who had come to East Africa in the late 1800s as laborers for the British. Amin had called the Asians in Uganda “bloodsuckers” and said that they were “milking the cow but not feeding it.” Nearly all of them would leave in the months surrounding the game. Mullen would personally help two Indian-Ugandan teenagers, whom he knew through his son’s schooling, flee the country, even sending one to live with his brother in Oregon. (“He changed my life forever,” she told me.)

Meanwhile, the Russians questioned every whistle against them. With both sides shouting in their ears, the refs became intimidated and their calls inconsistent, and the game took a nasty turn. “It was the roughest game I ever saw,” Mullen told me.

A crew-cut Soviet guard taunted a player named Willie Muganda by holding the ball out for him to try to grab. But Muganda was super quick and slapped the ball out of his hands, and both players tumbled across the floor. Muganda, whose shoulders had been built up from years of pulling nets out of the lake as the son of a fisherman, flipped the Soviet guard right over his hip and flat onto his back. He took offense at being tossed around and took a swing at Muganda. The refs threw him out of the game. Another CSKA player was ejected when he punched a Ugandan player while fighting for a rebound. The goodwill game had turned into a violent battle.

By the end of the second quarter, the Russians has a 12-point lead, and the roughness continued after halftime. Mullen had noticed that the Soviets’ best scorer was a bit of a hothead, and assigned Muwanga to guard him and make him lose his temper. So during one play, Muwanga plowed into him. The Ugandan fans were happy to see aggression from their team, and the drums and cheers from the capacity crowd became deafening.

That’s when the tension came to a head, with the Soviet coach complaining that the game was getting too rough. “Of course it was,” Mullen, clearly a biased witness, told me, “because his guys were beating the hell out of my guys.” Standing nose to nose, the Soviet coach and Mullen began yelling at each other through a bewildered translator. Eventually the two coaches sat down, each feeling a bit foolish at screaming what was received as gibberish by the other.

Perhaps Muwanga’s hard foul and the mutually incomprehensible shouting match had been the last straws. Despite holding an insurmountable lead, in the fourth quarter, the Russian coach finally called on his secret weapon; Petrakov was checking in. Kneeling at the scorer’s table, he was still almost as tall as the referee.

A couple of possessions went by without incident. But then a Ugandan player made a bad pass that was stolen by a CSKA player. The Soviet saw Petrakov waiting ahead of everyone down the court and sent a lob pass to the great mass of man. He rose and slammed the ball through the hoop with all the power drawn from his redwood-thick arms, and snapped the rim right off the backboard.

“It hung there by a bolt,” Mullen said. “Everybody’s standing there just stunned.”

“We had no replacements,” Muwanga told me, pulling out that laugh again. “Lugogo Stadium only had one set of rims.”

The drumming stopped. The cheering dissolved. The stadium was silent. “Everybody was wondering, What the hell happens now?” Mullen said. “It was more of a bewildered quiet than anything.”

Uganda is and was a poor country, and had become even poorer since Amin’s rule turned the country upside-down. And now the only indoor sports arena in the country was one hoop short. The game was over with time to spare. There would be no final buzzer. No Russian victory dance.

The Ugandans didn’t win. The Soviet team was too big, too polished, too experienced, and the Ugandans too raw, getting by on 99% heart. When the rim came down, the score reflected the difference in the teams’ skill levels. (The Uganda Argus reported that the Soviets had 87 points, but the Ugandan score in the Library of Congress’s archived edition is too blurry to read. It looks closest to 33.)

But Mullen had done something even better than win. The game ended with two fistfights, two ejected players, and the country’s only indoor basketball facilities destroyed. His team hadn’t been humiliated, and, though they had won, the Soviets didn’t look like untouchable superheroes. He couldn’t pull off a miracle on the court, but he got a small U.S. victory nonetheless.

After the CSKA game, the national team would travel to Alexandria, Egypt, to play in qualifying matches for the Pan African Games. The team didn’t even have tracksuits when they arrived. They were quarantined for two nights when it turned out two of the players didn’t have the proper vaccinations. The Ugandans were a group of amateurs, and were surprised to hear that some of their far-superior opponents from Egypt and Somalia played basketball as their jobs. They were creamed in Alexandria. “But it was a proud moment for us,” Cyrus Muwanga said, “representing our country.”

In September 1972, an attempted invasion from Tanzania by Milton Obote’s soldiers sparked seven years of institutionalized violence in Uganda, pushing basketball further toward the margins of the nation’s priorities.

Hilary Onek lost relatives and friends, including buddies from the basketball court, to Amin’s soldiers. “It was a difficult time for our country,” Onek said. “Within that period, the first three years of Amin’s rule, many of us left the country one way or the other.” Onek ended up going to Moscow not long after the game. He studied to be a civil engineer, learned to speak Russian, and lived in the USSR for nearly seven years. He came back to Uganda only in 1980, after a new coup, led by Obote, had exiled Amin to Saudi Arabia. In 2000, Onek went into politics and gained a seat in Ugandan parliament in 2001. He is now in the prime minister’s office in charge of disaster relief, looking after hundreds of thousands of refugees from war-torn countries.

James Okwera left Uganda in 1975. After the police came for his father, it felt like a different country from the one he grew up in. His father would live through it, but it spooked Okwera and his family. “I don’t know whether it was imagined or if it was real, but there was a perceived risk then for us,” he told me. They moved to Nairobi, where he continued the medical training he’d begun at Makerere University. In Kenya, Okwera played in a semi-professional basketball league as a paid ringer for the country’s best club teams. He ended up in the U.K., where he is about to retire as the clinical lead for stroke in a hospital in Yorkshire.

In 1978, Cyrus Muwanga went to the U.K. to take his medical exams. “Things were pretty bad in Uganda, so I just stayed,” he said. “I left to further my education as well, but the situation was getting pretty ugly at home.” He couldn’t really find good games in his adopted country, and took up squash and golf instead. But he still has a hoop at his house in northern England, and the time he competed shot for shot with a team of pros still brings a smile to Muwanga’s face. “It was one of those highlights in one’s life, games that you remember,” he said.

On Dec. 4, 1972, Mullen’s name appeared in an article in the Voice of Uganda that implied that he was plotting against the regime. It scared Mullen enough that he asked to be taken out of Uganda. His chief said to hold off and see what happened. (Nothing did.) Eventually, after the militant Palestinian Black September Organization murdered the U.S. ambassador in Khartoum, Sudan, in March 1973, even Mullen’s lax chief felt he was at great risk, since the PLO had by then formed a presence in Uganda. “They would probably love to kidnap someone like you if for no other reason than to beat whatever information they could out of you,” the chief told him.

Mullen left Uganda in June 1973. He worked for the CIA for two more years in Sudan before taking his family back to the U.S. In 1979, prompted by a run for the state senate the previous year — and against the wishes of the CIA, which forced several redactions — Mullen wrote a tell-mostly-all for the now-defunct Oregon Magazine. The Church Committee had by then revealed many illegal covert activities by government agencies, including the CIA, so Mullen wanted to assure his would-be constituents that he wasn’t an assassin. “They were asking if I’d used shellfish toxin to poison people,” he told me, “so I thought I’d clear the air.”

He lost the election by 88 votes and returned to teaching. He became a professor of African history at Southern Oregon University, and mostly retired in 2010.

The Mullen house is filled with keepsakes from the family's time in Africa. Scattered throughout the shelves are histories of Uganda and Amin, about whom Mullen’s been working on a book for years. After his Oregon Magazine piece came out, he landed some radio interviews and an appearance on Tomorrow, the late-night NBC talk show. In 2005, he gave a talk at a local library that aired on a cable access television show catering to the Rogue Valley in southwestern Oregon. “It was so intense in such a short period of time,” he told the SOU newspaper of his days in the CIA. “I really don’t care if anything that interesting ever happens again.”

Early on in our talks, I asked him if he was ever successful in recruiting a Russian agent. “I can’t tell you that because I just can’t," he said. "If I did, I would say no, and if I didn’t, I would say no, so either way the answer’s gonna be no, even if it’s yes. And that’s just the way the game is played.”

After our drive back from the coast, Mullen and I went to a steak restaurant for an early dinner. While waiting to be seated, Mullen saw people dancing in another room down the hall. “That’s the Texas two-step,” he said, and walked off. A minute later, I followed him to the other room, where Mullen was already dancing with a stunning younger woman, his jowls bouncing as he spun the stranger in circles. The song soon ended, and he walked past me and said, “Now that’s how you get to know Russians.”