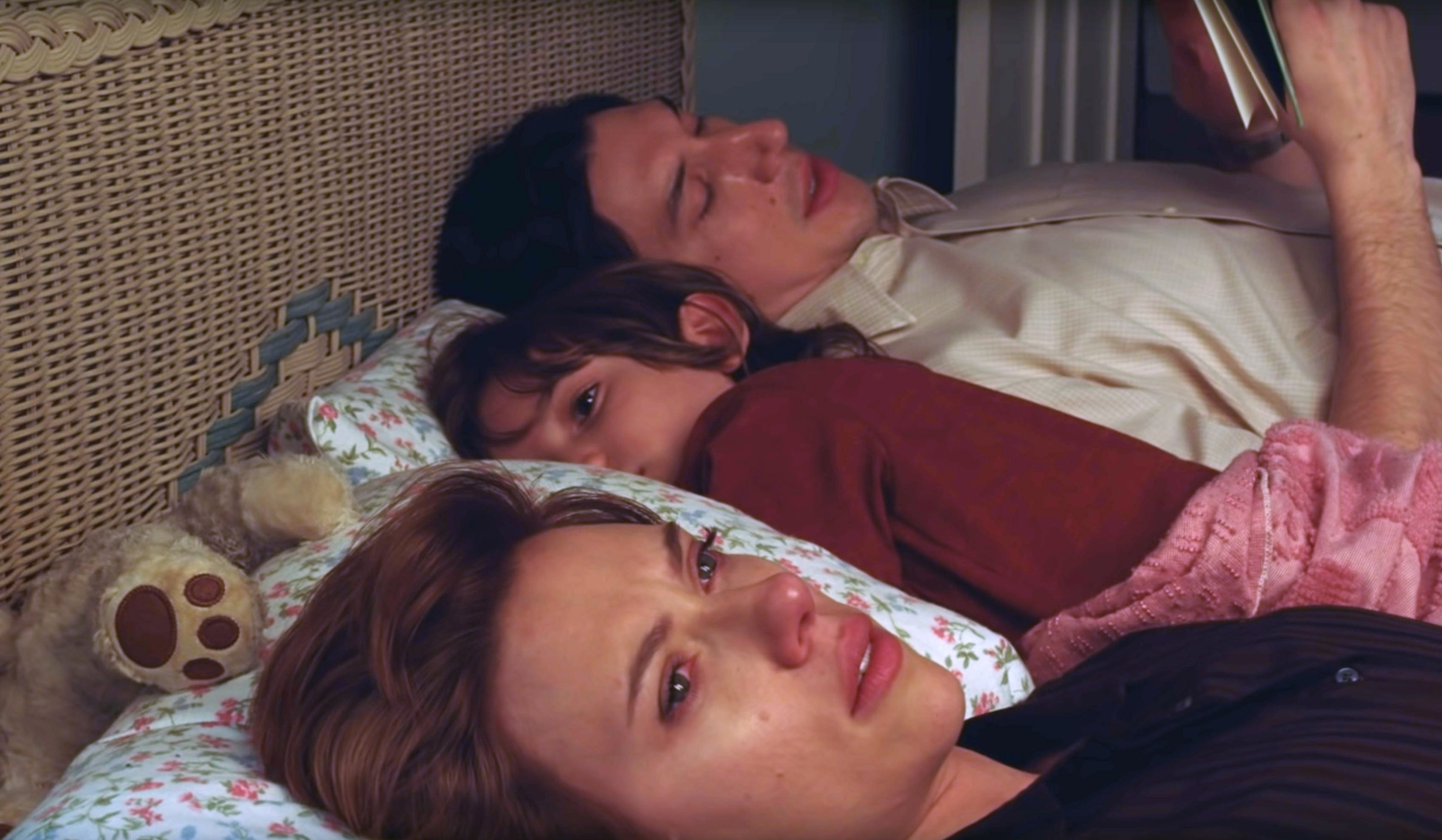

Before most people had had the chance to sit down and actually watch Noah Baumbach’s new movie Marriage Story on Netflix, a pivotal fight scene late in the film made the rounds on Twitter. Charlie (Adam Driver), a charismatic but demanding theater director, is having it out with his soon-to-be ex-wife Nicole (Scarlett Johansson). She wants to start over in her hometown of Los Angeles after a decadelong stint in New York as an actor in Charlie’s company, helping him make his dreams come true; the problem is that Charlie doesn’t want their son, Henry (Azhy Robertson) to live full-time with her across the country. After trying to deal with their separation amicably for most of the film, tensions boil over and both spouses end up screaming at each other.

Part of the reason that the clip went viral — before evolving into an all-purpose meme — was that people felt the need to weigh in on whether Driver and Johansson’s acting is actually any good. (My take: They’re good! Him especially.) But the other, more significant reason this scene has whipped the internet into a frenzy is because Marriage Story’s release came at the close of another year — another decade — in which mainstream American culture has attempted to wrestle with the dilemma of (white, middle class) heterosexuality and the question of whether it might be an ultimately doomed project.

All the jokes about Marriage Story painting a portrait of heterosexual implosion struck me as perfect examples of what Indiana Seresin, writing for the New Inquiry in October, called “heteropessimism,” which she defines as “performative disaffiliations with heterosexuality, usually expressed in the form of regret, embarrassment, or hopelessness about straight experience.” Heteropessimism “generally has a heavy focus on men as the root of the problem,” and its performances “are rarely accompanied by the actual abandonment of heterosexuality.” While some people do act — “choosing celibacy or the now largely outmoded option of political lesbianism” — most of them just lament the prison of straightness without attempting to either break free from or transform it.

The #MeToo movement, which kicked off in late 2017, forced a nationwide reckoning with gendered power imbalances and abuse in the workplace. But there has yet to be another comparably serious reckoning, nearly 50 years after Betty Friedan published The Feminine Mystique, with gendered power imbalances in straight couples’ personal lives.

This year, a trove of both fiction and nonfiction books, like Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s novel Fleishman Is in Trouble, about a marriage on the brink, and Lisa Taddeo’s Three Women, a report on the sad state of straight romance, explored the rocky terrain of heterosexuality at the end of the 2010s. Hollywood has also tried to reckon with straight men in crisis, in everything from The Irishman to A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood, but in ways that still position women as secondary characters, inevitable losers, or both. We’ve watched straight people try to find love under extreme and unsavory conditions — see: Love Island — just as we’ve watched them try to figure out how, or even if, to salvage love gone sour, like on Showtime’s docuseries Couples Therapy or via the tragically hilarious r/relationships thread on Reddit. We’ve rooted for millennial hetero love in work created by Phoebe Waller-Bridge and Sally Rooney, even when that love seemed hopeless or impossible. We've swooned over the March sisters, brought alive again thanks to Greta Gerwig's new adaptation of Little Women, who must contend with the bleak economic realities of straight marriage even as they try to find love too (in men or perhaps just in books). We’ve seen people give up on the doomed promise of straight romance altogether to embrace communal cult life instead; is there any more perfect paean to heteropessimism than Ari Aster’s Midsommar?

Giving up on the promise of heterosexuality does make a sort of sense (if joining a murder cult doesn’t quite). Feminism isn’t the bugbear it once was, and many men have been encouraged to embrace its tenets in both public and private life. But study after study has shown that, across socioeconomic classes, women’s increased participation in the job market has not been matched by nearly as significant an increase in men’s labor at home — not to mention all the other ways that casual sexism, even from the most enlightened of men, can manifest itself in straight relationships.

There has yet to be another serious reckoning, nearly 50 years after Betty Friedan published The Feminine Mystique, with gendered power imbalances in straight couples’ personal lives.

Online dating has offered us a trove of new data that confirms the hetero matchmaking world is as bleak as ever: Men’s desirability peaks at age 50, while women’s peaks at 18; advanced degrees can hurt women’s dating chances; men’s “preferences” are often just thinly veiled covers for straightforward racism. When attempting to find a partner, the odds remain stacked against women who aren’t conventionally hot, white, and smart but not too smart. And after making it through the dating world, women are still more likely than men to be unhappily married. Then, at the very end of their lives, men older than 85 report less life satisfaction if their spouse dies, while women whose husbands die actually get happier once the men are gone. Even making it to 85 unscathed feels like a feat for women when the world is still plagued by shocking levels of intimate partner violence. In the face of all these bleak statistics, who could really blame straight women for being less than thrilled with their own straightness?

Still, not even vehement heteropessimism seems to be encouraging straight people to actively question their own straightness. Like Seresin, and like most other lesbians, I’ve been on the receiving end of what feels like a million drunk straight women bemoaning their lot in life, insisting things would be sooooo much easier if they were queer. “That ‘men are trash’ is not something I am personally invested in disputing,” Seresin writes. “Yet in announcing her wish to be gay, the speaker carelessly glosses over the fact that she has chosen to stay attached to heterosexuality.”

The modern, progressively minded tendency to trash straightness at every turn — and I’m including gay people here too, though straight people doing it are way more annoying and, I’d argue, much more harmful — has meant that queerness among certain circles is placed on a pedestal that it doesn’t always necessarily deserve. Even though I don’t envy straight women for having to find a decent man in our misogynistic hellhole of a society, it’s not always easier to be a lesbian. For one thing, we have to deal with, you know, systemic homophobia. And for another, women can be shitty and abusive and, as bell hooks reminds us, just as capable of sexism as men are. Seresin points out, too, that “a certain strain of heteropessimism assigns 100 percent of the blame for heterosexuality’s malfunction to men, and has thus become one of the myriad ways in which young women — especially white women — have learned to disclaim our own cruelty and power.”

So, while heteropessimism is a perfectly understandable impulse, it’s not necessarily getting us anywhere. Seresin again: “To be permanently, preemptively disappointed in heterosexuality is to refuse the possibility of changing straight culture for the better.” But what might a true transformation of straight culture really look like?

One of the ways straight (white) women, in particular, have performatively distanced themselves from their own heterosexuality is through what Emmeline Clein, writing for BuzzFeed News, called “disassociation feminism.” Perhaps in response to stereotypes about female hysteria — Seresin mentions the Overly Attached Girlfriend meme — Clein and other women she’s observed “instead now seem to be interiorizing our existential aches and angst, smirking knowingly at them, and numbing ourselves to maintain our nonchalance.”

It’s been nearly five years since Alana Massey wrote her viral opus “Against Chill” in which she defines straight dating culture as the “Blasé Olympics.” It’s a culture that pressures you — especially if you’re a woman — to forgo “the language of courtship and desire, lest we appear invested somehow in other human beings.” Heteropessimism isn’t disassociation, exactly — Seresin calls it a “disaffiliation” — but it’s born of a similar impulse: an attempt to escape the inescapable.

Long before I developed any sort of feminist consciousness, I learned that, in order to be the kind of girl a boy wanted, I’d have to develop some level of ironic detachment from the objects of my desires. I was a proud little misandrist in the making, wearing my Boys Are Stupid, Throw Rocks at Them! shirt as often as I could in middle school. There was no greater satisfaction, at that time in my life, than beating boys at soccer during recess. I believed wholeheartedly in the girl power of the early aughts, even though, as much as I loved making fun of them or running them ragged on the soccer pitch, I desperately wanted a boy — any boy! — to think I was cute and cool. It was all incredibly confusing.

When I got older, my earliest hookups with guys were one part thrilling (male attention!) and three parts uncomfortable, gross, and humiliating. I got the impression that this was all par for the course. From high school through college, both my peers and pop culture at large signified to me that penises are nasty and blowjobs are a chore. Actually liking it would just make you a crazy slut, after all. Okay, so nobody really wants to do all this, but we just have to do it anyway, I thought as I blundered my awkwardly heterosexual way into my early twenties.

At the time, my friends and I were vaguely aware of the pop feminist discourse surrounding sex positivity, but we didn’t know about its sex-negative backlash; rather, we unwittingly tended to pluck out the worst tenets of both. We knew that straightforward slut-shaming was bad, but still looked askance at girls who got too messy in their boy lust; we volunteered for the university office that dealt with intimate partner violence, but didn’t know what to do when one of our friend’s boyfriends got so angry at her that he put his head through a sliding glass door.

At the beginning of my first year I told a dorm room full of my new friends that I thought I was bisexual, and after the dead silence that greeted this news, I decided not to bring it up again for another three years. Instead, with the kind but ultimately misguided permission of my sweet college boyfriend, I started exploring my interest in girls — at first, sort of secretly and shamefully. Then, after years of run-of-the-mill bad sex with boys who were becoming men, as well as a few too many instances of coercion and assault, I finally figured out that sex didn’t have to be so miserable all the time. I liked girls! Not only did I like them, I liked having sex with them!

Steeped as I was in a world insisting on heterosexuality as the norm — even when it made me, my now-divorced parents, and most of my friends profoundly unhappy — I hadn’t previously realized (or dared to believe) that lesbianism was an option for me. Sometimes I wonder if I hadn’t joined a rugby team my sophomore year and befriended, then later dated, the proudly out queer people I met through the sport, I might have just continued to be shunted along on the conveyor belt of heterosexuality toward my capitalism-approved future as a husband’s wife and the mother of his children.

Heteropessimism isn’t disassociation, exactly, but it’s born of a similar impulse: an attempt to escape the inescapable.

In Adrienne Rich’s famous essay from 1980, “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence,” Rich takes issue with the forces — like capitalism and pop culture — that have long convinced women that their “sexual orientation toward men … is inevitable,” even if heterosexuality is an “unsatisfying or oppressive component of their lives.” Rich notes that “there is no statistical documentation of the numbers of lesbians who have remained in heterosexual marriages for most of their lives” — a group of nameless and unrepresented women I think of often, whose ranks I easily might have joined. She references a letter the playwright Lorraine Hansberry wrote to the early lesbian publication the Ladder, which ran from the ’50s through the early ’70s: “How could we ever begin to guess the numbers of women who are not prepared to risk a life alien to what they have been taught all their lives to believe was their ‘natural’ destiny — and their only expectation for economic security?”

The “born this way” model of human sexuality would suggest that we’re all hardwired to prefer one or more genders; gayness, straightness, or bisexuality would then simply be our biological destiny. But just this year scientists have yet again debunked the existence of a “gay gene,” finding in a major study that multiple genes could influence the emergence of a person’s same-sex orientation — though “only 25% of sexual behavior can be explained by genetics, with the rest influenced by environmental and cultural factors.”

In other words, our sexual behavior is mostly shaped by the world we live in. And yet the mainstream assumption has barely changed since Rich was writing nearly 40 years ago: Everyone is presumed straight until proven otherwise (though for women, all the proof in the world is sometimes still not enough).

Heteropessimism has always had a role to play in the queer world too, but in the age of social media, that role has become much more clearly defined: It’s a way for strangers to question the boundaries of each other’s queer identities.

Declaring ourselves aesthetically, ethically, romantically, and just all-around superior to straight people is an everyday aspect of life on the queer internet. So are regular occurrences of bisexuals accusing lesbians of biphobia, and lesbians accusing them of lesbophobia in turn. These fights ultimately both come down to the question of whether or not bi people are at least adjacent to the straight world and, if so, whether they benefit to some extent from “straight-passing privilege.”

The actor Evan Rachel Wood, one of the most prominent voices on Bi Twitter, recently tweeted that her relationships with men are still queer, echoing sentiments expressed earlier this year by Miley Cyrus (before her separation) about how she queered her straight marriage with Liam Hemsworth. “You shouldn’t judge a book by its cover,” Wood wrote in her tweet thread. “A man and a woman can still encounter prejudice in a seemingly hetero relationship.” The tweets received a lot of love and support from other bi women who find that their queerness is invalidated when they’re in relationships with men; she also received some criticism from lesbians, who tweeted responses like, “if a bi woman and a bi man are walking down the street holding hands you think they’ll get decked by a mind reading homophobe?”

A lot of what’s deemed anti-bi or bisexual erasure on the internet is really just a version of heteropessimism: Jokes suggesting that women who willingly date men when they have the option not to are, if not bad or wrong, then just kind of embarrassing. The critic Andrea Long Chu is probably still getting angry @-replies to this tweet from last year: “str8 married bi girls are like those kids who studied abroad in college and five years later are still somehow weaving it into every conversation. like we get it christa you lived in madrid.”

Though bisexuality is still heavily stigmatized, I do reflect back on the years when I quietly identified as bi and enjoyed the very real social and economic privileges that came along with publicly dating my college boyfriend while sleeping with girls on the side. I thought I was a boring normie, rather than the cool radical I secretly longed to be, so I sympathize with bi people in straight-seeming relationships who feel like they’re not considered “queer enough.” That was my reality for a long time. But still, it turns out that the pressures from a minority subgroup to be sufficiently “queer” (whatever that really means) didn’t hold nearly so much sway over my choices as the enormous and practically incalculable pressures of compulsory heterosexuality.

Those pressures are so powerful, Rich writes, that many women fail to recognize how deeply we’ve internalized women-hatred until it takes “some permanently unmistakable and shattering form” in our own lives. For me, that moment was when I fell in love with one of the queer people I was sleeping with in college, who happened to be one of my best friends, and finally worked up the nerve — on the night before graduation — to end my straight relationship for good.

I don’t think the solution to heteropessimism is for everybody to suddenly decide to be gay (though I’d be into it). Political lesbianism, after all, didn’t quite work out the first time around, and our desires don’t necessarily make us any more morally righteous than those who desire differently than we do.

But even though becoming a lesbian didn’t automatically make me a better person, it did make me a hell of a lot happier. It’s scary to think that this wasn’t always going to be my destiny, and it’s really hard to imagine my life would be any better if I’d remained a disillusioned member of the straight world. I have to assume that, if everybody keeps complaining about heterosexuality’s dark sides while the institution itself remains a compulsory organizing structure for so much of American life, an extraordinary number of women (and men) might not know what they’re missing.

It should go without saying — but is worth repeating anyway — that queer relationships aren’t necessarily happier or healthier than straight ones. And one of the risks of heteropessimism is that it can actually obscure the ways in which gay relationships can also be plagued by toxicity and abuse. In her extraordinary new memoir In the Dream House, Carmen Maria Machado documents the year she spent in an abusive relationship with another woman. “I enter into the archive,” she writes in the book’s prologue, “that domestic abuse between partners who share a gender identity is both possible and not uncommon, and that it can look something like this.” In experimental, fragmented sections corresponding with different literary conceits, Machado places her own narrative within the all-too-limited tradition of lesbians and bisexual women grappling with their own experiences of abuse and assault.

Though all victims of intimate partner violence need to contend with a society (and a police state) that so often belittles, disbelieves, and even punishes them, queer women survivors are uniquely disenfranchised, because their female partners are often assumed to be incapable of really harming anyone.

In a recent essay about transmasculinity and feminism for the New Inquiry, Noah Zazanis writes about how, before transitioning, learning how he’d been harmed by patriarchy helped him to stop blaming himself for the violence done to him. But “it also meant that my conceptualization of my own reality, and my right to label these experiences as violence, was inextricably tied to seeing myself as a woman — or at least, within this binary framework of who harms and who is harmed, as not a man.”

The dominant narrative of domestic violence holding that men abuse women — something that is, indeed, devastatingly common in heterosexual pairings — also elides a less widely publicized story that LGBTQ people are just as likely, if not more likely, to experience abuse from their partners. And individual survivors, both in the midst of these relationships or long afterward, are often robbed of the opportunity and power to claim the facts of their experiences. “I wrote this book because I was looking for something that didn’t exist,” Machado told BuzzFeed News in November.

Heteropessimism, and our fixation on men’s fallibility, doesn’t only help straight women evade responsibility for their bad behavior; it can help lesbians do it too. I thought about that unpleasant little trick while watching the first few episodes of The L Word: Generation Q, this year’s reboot of the beloved Showtime series that ended its first run in 2009. Resident bad bitch Bette (Jennifer Beals), who’s running for mayor of Los Angeles, faces a major campaign setback when the husband of a woman she’d been sleeping with — who was also working for her at the time — publicly accuses her of the affair. (It’s a creepily prescient plotline following the recent resignation of member of Congress Katie Hill.)

After the rally, Bette’s commiserating with her two best friends, Alice (Leisha Hailey) and Shane (Katherine Moennig), who basically tell her she has nothing to worry about. Bette suspects that the scorned husband is just upset that his wife slept with a woman, which “threatens his manhood.” But neither Bette’s friends nor her campaign staffers think to admonish her for seducing, and sleeping with, one of her employees — a clear abuse of power, regardless of gender.

Another similarly cringey moment in the show arrived with the debut of its first special celebrity guest, soccer star Megan Rapinoe. I agree with lesbian critic Trish Bendix, who also got weird vibes from the segment in which Rapinoe goes on Alice’s talk show. “Alice is flirtatious with Megan, and I find that really gross in a journalistic setting, no matter the gender or sexuality of a reporter or guest,” she wrote. Though I suppose we’re supposed to find it charming that Alice nudges Rapinoe to admit that Alice is her celebrity crush, I instead just found it awkward and inappropriate. But again, because we’re so used to condemning men in positions of power for their behavior with women, and so unwilling to recognize the ways that women, and especially white women, can abuse their positions, heteropessimism (and its inverse — homo-optimism?) encourages us to let some of this stuff slide.

The goal here isn’t to pit queerness and straightness against each other, however. Rather, I’m curious about ways in which we can try to encourage romantic partners of all persuasions to be compassionate, mindful of their own power and privilege, and interested in transforming their own dating universes (whether queer or straight) for the better.

So how are we actually supposed to deal with the myriad pitfalls of heterosexuality without writing it off altogether? Diana Tourjée, a journalist at Vice, has been doing a lot of compelling and controversial work on this subject. She’s written beautifully about being “caught in a culture of male shame and discretion” as a trans woman whose partners prefer not to publicly acknowledge that she exists. She’s also done extensive reporting on straight men who find themselves attracted to trans women and has even made the case that transamorous men are a part of the trans community itself. She takes on the horrifying statistic that more than half of all trans women have experienced intimate partner violence, and the fact that many of them, especially trans women of color, will die from it.

Tourjée believes that cis men, instead of just being the perpetrators of these problems, are actually essential to solving them. She wites, “The longer cis men who love trans women believe their sexuality needs no definition or is best kept private, their bad behavior will continue to be passed down from one generation to the next, as trans women shoulder a burden that cis men could help carry.”

Heteropessimism, and our fixation on men’s fallibility, doesn’t only help straight women evade responsibility for their bad behavior; it can help lesbians do it too.

Tourjée’s writings about transamorous men have met a lot of online pushback from other trans and gender-nonconforming writers, thinkers, and activists. BuzzFeed News contributor Alex Verman, in the Outline, argued that attempting to normalize and desensationalize the straight men who date trans women contributes to the idea “that there is anything normal about a type of ‘love’ that results in three murders per day.” They reference Adrienne Rich’s work on compulsory heterosexuality to point out that “womanhood is often imagined as something that follows from men, rather than existing apart from or alongside them.” Heterosexuality creates gendered rules and expectations, rather than the other way around. To Verman, “Maybe the issue isn’t that men feel too much shame; perhaps, they don’t feel enough.”

This debate echoes more general feminist conversations about when, if ever, it’s appropriate to prioritize helping men achieve more healthy visions of masculinity, both to improve their own outlooks on life and to help them stop being so terrible to women. How much of the feminist project should actually be centered on men?

Journalist Liz Plank, for her part, thinks the project of male improvement is a worthy cause, as evidenced by her new book, For the Love of Men: A New Vision for Mindful Masculinity. So does journalist-turned-psychologist Darcy Lockman, who was inspired by frustrations in her own marriage to write All the Rage: Mothers, Fathers, and the Myth of Equal Partnership, an investigation into “why, in households where both parents work full-time and agree that tasks should be equally shared, mothers’ household management, mental labor, and childcare contributions still outweigh fathers’.”

Lockman reports that the third biggest reason for the dissolution of straight marriages is unfair division of labor at home. Rather than succumb to a heteropessimistic impulse to assume that boys will be boys, Lockman dives deep into the makings of men and women who grow up to take on heterosexual partnerships, debunks myths of “maternal instinct” and biologically essentialist gender roles, and explores all the ways in which men evade their responsibilities to their wives and families, from “passive resistance” to “strategic incompetence.”

Lockman’s book is chock-full of fascinating findings about women lowering their expectations so they can stand to be married to people who aren’t pulling their full weight. One of the ideas I found most compelling is that, in France, where there’s less explicitly feminist rhetoric, women report a lot less anger at and frustration with their husbands — in large part due to “distributive care” of the French state. French women’s husbands aren’t doing anything significantly different than their American counterparts, but in France, free universal daycare and other social programs take on a significant amount of the burden of raising children; American mothers don’t receive enough help from their husbands or the state.

Lockman also notes that, over the past few decades, American women have always been likely to report high feelings of communality, like expressivity, warmth, and concern for the welfare of others. Men, meanwhile, are barely any more invested in communality than they have been in decades past — those numbers are still, as always, quite low.

If men are so resistant to communality, what if we were to bring the communality to them? France and other countries with progressive social programs have certainly not solved the problems born from sexism or misogyny, but encouraging a culture in which we are all responsible for each other’s well-being — rather than merely responsible for our own nuclear families — could have real, radical results. Audre Lorde has written about how the sharing of work can also be the sharing of joy, which “makes us less willing to accept powerlessness, or those other supplied states of being which are not native to me, such as resignation, despair, self-effacement, depression, self-denial.”

In her essay on heteropessimism, Seresin writes that the concept is often framed as an anti-capitalist one: “a refusal of the ‘good life’ of marital consumption and property ownership that capitalism once mandated. Yet this good life, which was always withheld from marginalized populations, is now untenable for almost everyone.” Heteropessimism hasn’t actually succeeded in pushing back against capitalist forces at all; it’s only helped encourage a change of subject. “If the couple was the primary consumer unit of the past,” Seresin argues, “today this has collapsed, or more accurately been replaced by a new dyad, the individual consumer and her phone.”

It’s tempting to consider that straightness is so doomed that our only option, for queer and straight people alike, is to disavow heteronormativity altogether — eschewing marriage, family, all of it — and simply focus on ourselves; it’s us against the world. But what if we instead used our heteropessimism to encourage each other to reach beyond the bounds of the self — and beyond the bounds of our romantic partnerships and nuclear families — to imagine a better world for us all?

The problem with heterosexuality’s stranglehold on the organization of American life isn’t only the way it produces and reproduces gender roles that limit both men and women. It also keeps us trapped in the assumption (and the political reality) that finding a mate is our best chance at survival. I choose to believe — to hope — that together, we can find a better way. ●