On Tuesday night, I was reporting on the protests against police brutality and racism in New York City when an NYPD officer threatened to arrest me. It was a couple hours after the city’s newly established curfew, and a colleague and I were trying to figure out what was happening at the Manhattan Bridge. Thousands of nonviolent protesters who’d marched from Brooklyn were now being barred entrance into Manhattan by lines of officers in riot gear. All of Confucius Plaza was crawling with police, while a low-flying helicopter buzzed ominously overhead, illuminating the protesters who were boxed in and shouting to be freed. It was one of the most surreal scenes I’ve ever seen, in the city I call my home or anywhere.

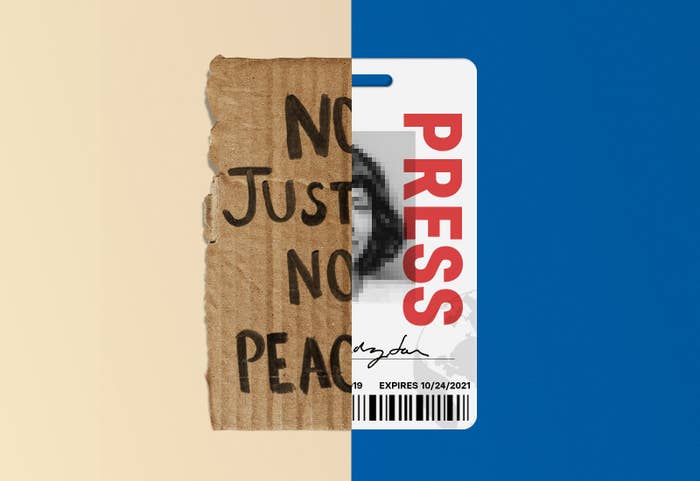

My colleague Tilli and I were standing with a group of onlookers who were chanting “Let them go!” across from the entrance to the bridge when cops suddenly started pushing us back. We thought they might be about to start kettling the protesters, forming a circle in which to trap and potentially arrest them; it’s a tactic that the NYPD has been using this week to round up people deliberately protesting after the citywide curfew. As I tried to get closer to the crowd on the bridge, I showed an officer my press pass, but he barked that it wasn’t NYPD certified. “You’re in violation of the curfew,” he said. “If you don’t go home now, expect to be arrested.”

The kettling never came to pass. Eventually the protesters were encouraged to turn around and try their luck on the Brooklyn end of the bridge — where a huge police presence awaited them. Some protesters were placed into police custody while most were allowed to march on unimpeded after more than an hour trapped in terrifying limbo. That incident would ironically end up being one of the more peaceful encounters documented between police and protesters in New York City this week. Residents fighting for their right to peaceful assembly — or else simply doing their jobs, as reporters or delivery drivers or legal observers or healthcare providers — have been routinely rounded up, beaten bloody, arrested en masse, and, due to a judge’s recent ruling, detained for 24 hours or more in the city’s coronavirus-infested jails.

Not only do the president and his supporters deride the media as the “enemy of the people” and gleefully advocate for our destruction on a daily basis; we’re now seeing police officers across the country blatantly violate journalists’ First Amendment rights, as well as our classifications as essential workers who are supposed to be exempt from curfews in cities like New York. According to a new analysis by the Guardian and Bellingcat, an investigative journalism website specializing in open-source intelligence, there have been at least 148 instances of journalist arrests or attacks during coverage of these protests — they’ve been “blinded, beaten, maced and arrested by police in numbers never before documented in the US.”

Mayor Bill de Blasio, who had seemingly avoided watching any of the other hundreds of stomach-churning viral videos of police brutality against protesters and essential workers, finally spoke up on Thursday night about “the troubling video” of an arrested delivery worker. “Food delivery is essential work and is EXEMPTED from the curfew,” he tweeted. “Same goes for journalists covering protests out doing their jobs. They are essential workers, too.” It remains to be seen whether the NYPD will heed the mayor’s words, but all evidence indicates that yet again, “essential workers” during the coronavirus pandemic aren’t being paid or treated as though they’re really so essential.

When I was able to narrowly avoid arrest on Tuesday and return safely to my home, I thought about how ridiculous — and how troubling — it was that even my supposedly protected status as a reporter almost didn’t protect me after all, as has been the case for multiple colleagues of mine this week. Though de Blasio’s press secretary has indicated reporters shouldn’t need official NYPD-certified press passes to do their jobs at the protests this week, that hasn’t filtered down to police on the ground. Those passes are notoriously difficult to obtain, even for those working at name-brand news outlets, let alone for freelance and citizen journalists. A detective told me the department isn’t even processing press cards until further notice “due to the current situation.” It’s disconcerting that the police are tasked with deciding which journalists can move freely on the streets when the question of their own brutality is currently the biggest story in the world.

Police descending on protesters who were completely peaceful. Completely chaos. People screaming. Police grabbed my arms and tried to cuff me but let me go when I showed my press pass.

But I feel even more uncomfortable with the idea that I’ve been afforded any special status at all. As the journalist Wesley Lowery recently pointed out in an excellent Twitter thread, “police have been blatantly ignoring the First Amendment rights of protesters — responding to their constitutionally protected speech with state violence — for years,” and “journalists are not a specially protected class of 1st Amend users. It is no *more* outrageous for a reporter to be targeted with tear gas or rubber bullets or arrest than it is for a citizen peacefully assembling & chanting (no matter how angry) to be met with that same force.”

And yet some in our profession — especially those who haven’t experienced discrimination, from the police or otherwise, due to their race or gender or socioeconomic status — are all too eager to rail against journalist suppression while downplaying or even championing police efforts to harass or arrest protesters. The National Press Club earlier this week penned an open letter, signed by 28 press organizations, calling “for police nationwide to halt use of violence, arrests against journalists covering protests,” but made sure to clarify their “utmost respect” for law enforcement. “The job you are being asked to do is difficult and requires extraordinary courage and discipline and we can see that most of you are working diligently to restore a sense of peace and calm to your cities,” the letter begins. “Thank you for your best efforts.” Press freedom is, of course, essential and worth fighting for, but that so many journalism groups would lend their names to a letter commending “most” cops for restoring “peace and calm” when hundreds of protesters are being brutalized on a daily basis is a sign, to me, of an industry in great and terrible crisis.

It’s disconcerting that the police are tasked with deciding which journalists can move freely on the streets when the question of their own brutality is currently the biggest story in the world.

For one thing, to advocate for journalists’ rights without doing so just as passionately for the rights of protesters — which are, again, enshrined in the same constitutional amendment — is to deny that, as Wesley Morris wrote this week for the New York Times, “the most urgent filmmaking anybody’s doing in this country right now is by black people with camera phones.” In the United States and around the world, regular citizens’ abilities to record the abuses and brutalities they’ve faced while fighting for a better future have exposed long-standing injustices like police violence to communities who’d been previously sheltered from it, and therefore inured. A new study from Monmouth University released this week found that 57% of Americans believe police are more likely to use excessive force against black people, compared to 34% in 2016. It was citizen journalists and other social media users who made Ferguson “America’s Arab Spring,” and have continued to do the work ever since.

Nothing about police behavior has fundamentally changed — white people are now just seeing more of it, and are now more likely to actually believe what black people have been telling us for decades. Whether or not reporters with a piece of employer-issued plastic around our necks are on the ground, witnessing and documenting the atrocities or experiencing them ourselves, the ever-mounting video evidence from anyone with a smartphone is increasingly impossible to ignore. When Gov. Andrew Cuomo falsely claims that NYPD officers haven’t attacked peaceful protesters with batons, a combination of journalist and protester videos can prove him wrong.

The George Floyd demonstrations are just the latest and most incendiary events to trouble the boundaries between journalists and the activists on whom we’re reporting. More reporters are realizing that they need not — and should not — always take law enforcement at their word.

In the horrifying incident of Buffalo officers shoving an elderly white man to the ground, where they left him bleeding from the head, police originally said he “tripped and fell.” Even Cuomo stepped in to call for the officers involved to be suspended and investigated, having previously ignored every other appalling video of brutality against Black and brown bodies at the hands of his officers. (The entire Buffalo riot squad has since resigned from the team, though not their jobs, in solidarity with their disgraced colleagues.) Every night we witness brutality and abuse just to wake up to our elected officials denying what we’ve seen with our own eyes. On Friday, de Blasio even accused WNYC radio host Brian Lehrer of not being “objective” for accurately summarizing police activity in New York this week. Luckily, we’re equipped to report the facts. And if officers are harassing and arresting even the people they aren’t “supposed” to, from journalists to lawmakers, what might they be getting up to in the marginalized communities they’ve been over-policing for decades now? Especially when the evidence isn’t captured on video, police testimony puts people in jail every day.

“One reason journalists are conditioned to ignore saying anything on the rights of protesters being violated by the gov is cause they’re scared that would be inappropriate ‘activism,’” Lowery noted in his thread, “while advocating loudly for their *own rights* is seen as necessary and noble.’” That’s why some newsroom leadership — including my own — have discouraged their staffers from contributing to bail funds to free arrested protesters and workers, arguing as Business Insider editor-in-chief Nich Carlson did recently that those donations “call into question our credibility in covering the protests.” (After a Daily Beast report on employee outcry, the company clarified the editor’s comments, referring to the policy as a mere guideline to use “best judgment.”) Most news outlets have ethics guidelines that discourage journalists from donating to “political” causes — the question newsroom leaders face is whether supporting the release of protesters from police custody for exercising their First Amendment rights, as they likely would for journalists, is really a “political” cause rather than one of free speech and human rights.

The burden of supposed objectivity has fallen especially heavily on journalists of color, in particular Black journalists, during the 2020 protests and long beforehand. Karen Attiah of the Washington Post recently noted, “This is another problem with the lack of diversity in our newsrooms. Too many … treat serious life or death issues as their fodder for intellectual calisthenics, while many of us and our communities are literally under siege from dangerous rhetoric and racist policies.”

Every night we witness brutality and abuse just to wake up to our elected officials denying what we’ve seen with our own eyes.

In the past week a wave of Black journalists at the New York Times, as well as hundreds of their colleagues, publicly condemned an opinion piece by Sen. Tom Cotton, which called for a military crackdown on protesters. It was a protest that felt both unprecedented and inevitable — just one of the long-strained dams finally broken during These Extraordinary Times. Not only does the Times have a strict social media policy about criticizing colleagues in public; journalists of color have described being prohibited or discouraged from calling out racism in the industry and beyond it for fear they’ll be labeled biased activists.

At least one New York Times staffer and other (white) journalists have seized the moment to dig in their heels about “safetyism,” quelling “bad opinions,” and the “free exchange of ideas”,” delegitimizing and insulting their Black peers in the process. But the shakeup at the Times over publishing a fascist op-ed offers us the tiniest window into a potential future of journalism that doesn’t have to submit to bothsidesism. Newsroom leaders often seem more concerned about conservatives perceiving them as biased than they are concerned about the prejudice and human rights abuses faced by marginalized communities that include their own employees. In prioritizing false equivalences over truth, these journalists are in dereliction of their duty to their readers and to each other.

Months into the coronavirus pandemic, when antiracist protests have swelled to hearteningly staggering levels — and police crackdowns have responded in kind — journalism is just one of many industries that will have to make a case for itself in whatever world we build out of all this. I hope white journalists can use the opportunity to finally stand in solidarity with Black journalists, and with protesters, and with all workers against state-sanctioned violence. It’s our job to hold abusers of power to account. We can’t stop now. ●