Today Pete Buttigieg is polling within the top four candidates nationally and first in Iowa (if near-last among millennials), but back in March, when he first made his case to a national audience during a CNN town hall, “Mayor Pete” was still a nobody. Moderator Jake Tapper asked Buttigieg, who had served as the openly gay mayor of South Bend, Indiana, during now-vice president Mike Pence’s tenure as the state’s governor, whether Pence would make a better president than Donald Trump. In his answer, Buttigieg took the assumptions the evangelical right often makes about gay people — that we’re conniving, amoral perverts — and deftly redirected them toward Pence himself.

Pence, who has an extensive anti-LGBTQ record, seemingly “stopped believing in scripture when he started believing Donald Trump,” the mayor mused, making clear that his own interpretation of the Bible is very different than Pence’s: “It’s about protecting the stranger and the prisoner and the poor person … and his has a lot more to do with sexuality and a certain view of rectitude." Buttigieg implied that Pence was using Christianity to carry out his own weird obsession with, and criminalization of, other people’s private intimacies — which would make him quite a hypocrite since he’s now “the cheerleader for the porn star presidency.” In Buttigieg’s rendering, Pence wasn’t the wholesome, Christian family man with good old-fashioned charitable values. Buttigieg was.

I admired Buttigieg’s cleverness in setting up that role reversal, and apparently, so did Democratic strategists and a record number of donors. But at the same time, it unsettled me that Buttigieg’s criticism of the vice president didn’t focus directly on the devastating effects that anti-LGBTQ policies can have on the lives of gay people. Rather, Mayor Pete took the opportunity to make that case that he’s a better Pence than Pence is: a better Christian, a better family member, a better man.

To me, and to a lot of other gay progressives — from ACT UP activists to the queer wing of the DSA — that moment in March made it suddenly and disappointingly clear that Buttigieg’s rise was made possible by a gay civil rights movement that has focused above all else on marriage equality and assimilating LGBTQ people into the mainstream. In lieu of working toward a radically different vision of a more just society, Gay Inc. agreed to settle for the same bad deal that unwealthy straight people already have.

His win would be a constant reminder of how much the gay rights movement had to give up in order to make it this far.

In general, Buttigieg makes the case that gay people like him, and like me, deserve to belong — in our families, in our churches, and in our communities — just as much as straight people do. He’s right; we do deserve to belong. But Buttigieg is also effectively arguing that queer people’s rights should derive from the very institutions we’ve only recently gained (tenuous) access to, like marriage and the job market. He’s insisted that universal coverage for things like pre-K, Medicare, and college education — policies I believe in, which would guarantee coverage to every individual, regardless of their marital or employment status — isn’t only financially impossible, but wasteful and unnecessary. (Why rely on the state when you’ve got private corporations or the conservative-approved nuclear family?)

It’s not all that surprising, then, that I or other progressive voters who might have been initially optimistic about the prospect of a viable queer candidate quickly soured on Buttigieg after the brief thrill of his early rise. Since March, the mayor has steadily shuffled toward an open spot in the center of the field, and pivoted to attacking further-left candidates like Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders for what he positions as their pie-in-the-sky, unrealistic plans for gun law reform, universal free college, and Medicare for all. This week, he released the names of his clients from his time working as a consultant at McKinsey following intense public scrutiny over his involvement at the firm. But the disappointment — and even anger — of the “Let’s Get Buttigieg To Quit” faction is different, and much more specific, than general progressive frustration with a more moderate candidate.

For decades now, queer radicals “against equality” have argued that, from marriage to the military, “seeking inclusion in a system that’s based on institutional and economic exploitation is an unacceptable path forward.” LGBTQ people, particularly the most marginalized among us, will never thrive in a country powered by capitalism, the military-industrial complex, and mass incarceration. But they — we — are clearly a minority within a minority.

The mainstream gay rights movement, which claims marriage equality as its crowning achievement, has meanwhile pivoted toward promoting workplace protections for LGBTQ employees while continuing to traffic in representation politics. The more LGBTQ people we see on TV and in leadership roles, the representation theory goes, the more normalized (and therefore, hopefully, more accepted) we become. And what bigger win for LGBTQ visibility could there be than a wholesome, Christian family man and his husband in the White House?

But as monumental as a Buttigieg presidency would be for gay visibility — and it would indeed be monumental — his win would also be a constant reminder of how much the gay rights movement had to give up in order to make it this far. Buttigieg’s ascendance is at least in part a byproduct of the least ambitious, most compromised impulse of a decades-long fight for queer rights winning out over demands for something better.

A few days after that CNN town hall, I attended a Buttigieg campaign event to report on the scene at a posh restaurant and bar in Chelsea, where a few dozen of his new donors had gathered to meet the man himself. Buttigieg was introduced by New York City Council speaker Corey Johnson (who praised him for “making Mike Pence crazy on a daily basis”) before he launched into his stump speech, which, since the beginning of his campaign, has always been in part a call-to-arms about rebranding supposedly Republican values as Democratic ones.

“We are the party of freedom,” he said. Americans cannot be free if they lose their jobs and therefore lose their health care, he suggested; Americans cannot be free without the right to make their own reproductive health choices; Americans cannot be free in the face of white nationalism. (More recently, having distanced himself from Medicare for All, he’s amended the health care line to: "You’re not free if you don’t have health care, but you should have the freedom to choose whether you want it,” which is a bit of a head-scratcher.) Buttigieg tends to evoke his own marriage in this context, too, using an oft-repeated line that he was only free to marry his husband “because of a single vote on the Supreme Court.” He argued that Democrats should claim not only to be the party of freedom, but of opportunity, service, and family.

The crowd was impressed. One man told me he loved that Buttigieg showed the world a happy, stable gay marriage: “We can be the party of family values.” His friend agreed: “It’s so nice to see. He’s not harping on about the fact that he’s gay, but he’s proving that we can be just like everyone else.”

The fact that Buttigieg has been on the cover of Time magazine with his husband, whom he’s also held hands with, kissed, and called “my love” in ads and interviews, is all evidence that his campaign is a historic one. I’ve spoken with many gay men who thought an openly gay candidate would never have a serious shot at the presidency in their lifetimes, let alone four years after the Supreme Court marriage equality decision, and seeing Buttigieg thrive — regardless of whether they’d actually vote for him in the primaries — has moved some of them to tears. “He is, quite simply,” Andrew Sullivan wrote in April, “what many of us in my generation of gays fought for and rarely believed could happen.”

But it’s hard for me not to take a more cynical view of the way Buttigieg’s campaign has packaged the world’s most straight-palatable gay narrative: He is a practicing Christian who, according to an op-ed he wrote in 2015 for the South Bend Tribune, believes being gay is no more significant an identity marker than “having brown hair,” and who is safely and monogamously partnered with the first guy he ever dated (whom, he’d like you to know, he met on Hinge — not Grindr). Buttigieg doesn’t have to contend with the implication of a seedy gay past or present; he’s already fulfilled the gay assimilationist dream of marriage, the white picket fence, and a couple of rescue dogs.

Realistically, the US electorate is more likely to vote for someone who presents himself like Buttigieg than for a polyamorous bottom queen.

There’s nothing wrong with marriage and monogamy (or rescue dogs, especially); Buttigieg is no less gay for his choices than your typical orgy-attending, polyamorous Brooklyn bottom queen is for theirs. And realistically, the US electorate is more likely to vote for someone who presents himself like Buttigieg than for a polyamorous bottom queen. To some extent, Buttigieg is only doing what he needs to do to get by. So I understand why some queer critiques of Buttigieg focused on his “wonder boy” perfection or his buttoned-up family man affect — like the July New Republic essay by author, critic, and ACT UP activist Dale Peck on his “Mayor Pete Problem,” which the site ended up unpublishing after a wave of public outcry condemned it as a “homophobic hit piece” — have raised his supporters’ hackles.

But especially when the critique is coming from another gay person, I do think it’s important to distinguish between anti-gay rhetoric and all-purpose snark — or deeply felt grievance. Jezebel’s Rich Juzwiak pointed out that Peck, rather than simply reexamining the symbolic value of any gay man running for president, was “probing what it actually means for this particular gay man to be a serious presidential candidate.” And this particular candidate, to Peck and a lot of radical queer activists, has happily set aside the loftier ideals of a former generation nearly decimated by the AIDS crisis in favor of playing the nice, well-behaved gay man who’s choosing convention over revolution.

Whether or not his campaign has actively presented him as a “wonder boy” — someone whose Rhodes Scholar smarts have been hailed in the media far more often than Cory Booker’s, who is compared favorably to apparently shriller, angrier candidates like Warren and Sanders even as he attacks them in debates and ads — Buttigieg has clearly benefited from the cultural cachet afforded by his whiteness, maleness, and academic pedigree. Some of Buttigieg’s supporters have actually weaponized his sexuality, too, using cries of anti-gay prejudice to turn around and discriminate against other groups, like spreading the insidious and racist lie that homophobia is the reason Buttigieg is floundering with black voters.

If some white gay men would like to prove they’re no different than your average married straight bro — that they believe in “family values” too! — in order to receive less scrutiny from a prejudiced world (and/or because that’s what they’re actually into), then all power to them. But Buttigieg isn’t just your average white gay guy — he’s running for president, and pretty successfully so far. In doing so, he’s laying out a very public roadmap for gay success at the national level, which in all likelihood wouldn’t be possible without the assimilationist activism of the marriage equality movement. The best way for queer people to get ahead, it seems, is still to act as though we are just like everybody else.

On a warm June morning in June 2016, I was waiting in a long line outside of the White House to attend President Barack Obama’s final LGBT Pride Reception. A gay couple who looked to be around my age were in line ahead of me. When we got to chatting, I learned they were Chasten and Pete Buttigieg, the mayoral first family of South Bend, Indiana. Pete was relatively quiet and deferential; Chasten was funny and animated. I didn’t know then that Pete was a Democratic Party darling and an Obama protegee; at the time, he was only another gay guy, a fellow millennial, a person I’d bumped into at a party.

Following the reception, I was chatting with a group of people outside of a hotel afterparty when I heard somebody from the street yell, “Hey, BuzzFeed!” I turned; it was Pete and Chasten, who’d rolled down their car window. One of them, I couldn’t tell which, waved at me and shouted: “Hit us up if you’re ever in Indiana.” (Earlier this year, I tried to do just that, pitching a profile of Buttigieg when he first started gaining momentum in the spring. But the interview never came through, and I got the sense that his campaign staff wasn’t interested in any more coverage focusing on his gay identity. In a recent follow-up email with Lis Smith, one of Buttigieg’s senior advisers, she recalled that we were “asking for a fair amount of access to Pete and Chasten at home,” and “there were a lot of outlets asking for access like that at that time. Everyone got [the] same answer — was nothing personal or specific to you.”)

While we were still inside the White House for the pride reception, we watched Obama address the room of LGBTQ activists, advocates, politicians, celebrities, and journalists. He was nearing the end of his second term, and he looked tired enough to prove it. In spite of myself, I felt overwhelmed with emotion hearing the president list all the LGBTQ rights that had been expanded and, in some cases, enshrined into law under his tenure: the end of “don’t ask, don’t tell”; the evolving case law on LGBTQ rights, which Obama’s Equal Employment Opportunity Commission had interpreted to be covered already by existing civil rights law banning sex-based discrimination; and, of course, the Supreme Court’s marriage equality decision, one year earlier.

The Obergefell v. Hodges decision had come down early in the morning on June 26, 2015, during my first weeks as BuzzFeed’s LGBT editor, and I spent the day in a chaotic work spiral. Once I’d emerged many hours later, my then-partner and I wandered over to the Stonewall Inn in the West Village that evening, which was absolutely mobbed with people. Then, too, in spite of myself, I felt choked with emotion, overwhelmed with the joyful spirit of my community. Even as a self-described radical queer who claimed to prioritize so many other LGBTQ issues over marriage, I nonetheless took a Stonewall selfie and captioned it (ugh) #LoveWins. None of us knew what was coming.

“Mayor Pete is using the family as a locus of social control in the most cynical, conservative way.”

Now, a couple of years into the Trump presidency, Buttigieg has joined his fellow Democratic candidates in vowing to roll back the current president’s various anti-LGBTQ measures, like reversing the ban on transgender people serving in the military and protecting LGBTQ asylum-seekers. Some of his plans, like calling for the "beginning of the end of AIDS," are distinctive in that they bear the weight of his own personal experiences: as a gay man, he's currently unable to donate blood because of outdated "ignorance and bigotry." He also supports passing the Equality Act, which would amend the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to explicitly prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity in areas like employment and public housing. Where Buttigieg has fallen short in queer leftists’ eyes, however, is on issues that don’t necessarily have an obvious connection to LGBTQ rights, but nonetheless radically impact the lives of LGBTQ people, like health care, housing, and education.

Over Thanksgiving weekend, a new Buttigieg TV ad airing in Iowa started making the rounds on Twitter. “I believe we should move to make college affordable for everyone,” Buttigieg says in the ad. “There’s some voices saying, ‘That doesn’t count unless you go even further, unless it’s free even for the kids of millionaires.' But I only want to make promises that we can keep.” (As Politico reporter Alex Thompson pointed out, this indirect dig at Sanders and Warren overlooks the fact that they’ve both suggested programs that would be paid for primarily by taxes on millionaires and billionaires.)

In a Twitter thread responding to Buttigieg’s new policy position, professor and BuzzFeed News contributor Steven Thrasher pointed out how strange it is that 18-year-olds — legal adults who can be “sent off to war to die” — are still legally dependent on their parents for things like health insurance and student aid. “By demanding LGBTQ young adults specifically (& young adults in general) be bound to their parents’ earnings … Mayor Pete is using the family as a locus of social control in the most cynical, conservative way,” he wrote.

Thrasher points out that an unfortunate historical turn in the gay rights movement was the pivot from advocating for universal health care to the less ambitious goal of expanded private health insurance access through same-sex marriage, which has left gaping cracks in the system. Given those gaps, a young person (or anyone) without familial ties, which is very common in the LGBTQ community, might be left without coverage granted by state-sanctified marriage, family, or employment. (Buttigieg’s “Medicare for All Who Want It” program, which is decidedly not Medicare for All, emphasizes “affordability and choice.”)

“Pete is trying to reinforce the existing, conservative social order,” Thrasher finished. “Bernie is offering something akin to queer liberation by way of liberated access to learning & health.”

But of course, Bernie isn’t gay. And whether he’d be better for LGBTQ rights than an actual gay person isn’t easy for the mainstream LGBTQ rights movement to consider, because of how deeply the movement has become ensconced in individual representation politics. If you think GLAAD-style visibility is everything — or that the fight for gay rights ended with marriage equality — how could you resist the opportunity to elect Pete Buttigieg?

In Buttigieg’s bestselling book, Shortest Way Home: One Mayor's Challenge and a Model for America's Future, he admitted that, after coming out later in life, he didn’t want to become “a poster child for LGBT issues.” But were he to be elected, he’d be the first openly gay president in American history; he’s on that poster whether he’d like to be or not. It only makes sense, then, for his campaign to court LGBTQ PACs and individual donors who are motivated by the idea of a man and his husband in the White House.

The Victory Fund, which is the largest political action committee dedicated to electing LGBTQ politicians to office, endorsed Buttigieg for president over the summer. Annise Parker, the head of the fund and herself one of the first openly gay mayors of a major US city (Houston, where she was in office from 2010 to 2016), said in her endorsement that Buttigieg’s candidacy is not only "important for our community, but ... important for our country. America needs us to step up, just as it needs Mayor Pete to step forward. Mayor Pete's progress is our progress; his journey is our journey."

It seems as if the neoliberal impulse to make the establishment more diverse will always be an easier sell to the mainstream than putting someone in power — of any identity — who wants to dismantle the establishment itself.

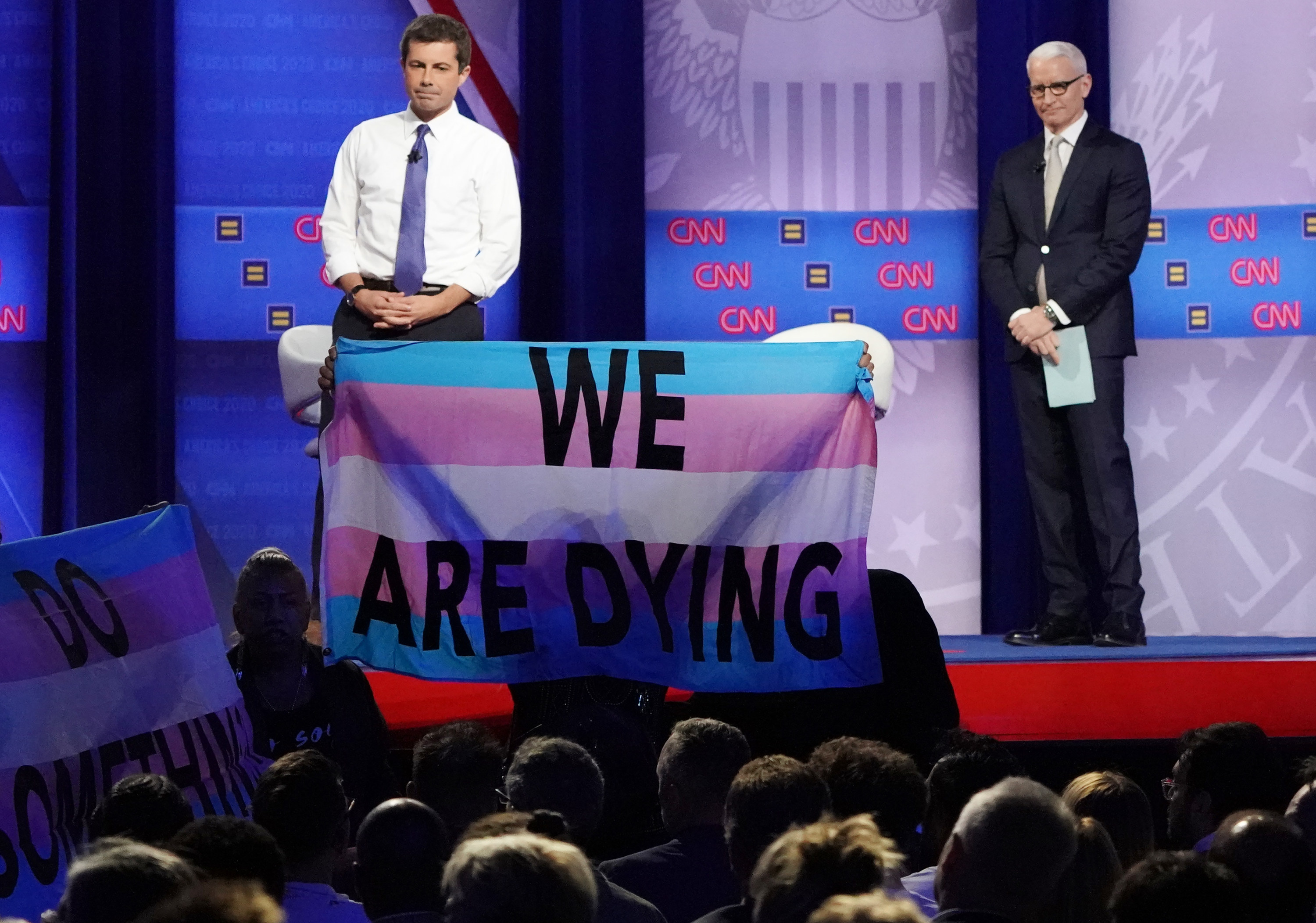

LGBTQ people in the US aren’t a monolith; LGBTQ progressives aren’t either, for that matter. But the question of whether or not one believes “Mayor Pete’s progress is our progress” matters — because it speaks to the uncertain future of the LGBTQ movement at large. Recent shakeups at big LGBTQ nonprofits and advocacy arms like the Human Rights Campaign and the National Center for Trans Equality have made all too clear that racism and transmisogyny still plague the movement, and that assimilationist strides toward equality and inclusion haven’t necessarily benefited the community’s most marginalized members.

To what extent was someone like Edie Windsor’s progress really our progress? Windsor, the lead plaintiff in United States v. Windsor, which overturned the Defense of Marriage Act in a landmark legal victory for LGBTQ rights in 2013, made it possible for many tens of thousands of gay people in the US to marry, an impact which can’t be understated. But I can’t help but think of the fact that Windsor’s case ultimately boiled down to the fact that, as Yasmin Nair has written, she was required to pay estate taxes she didn’t want to pay. In winning her case, Windsor made it easier for herself and other wealthy gay people to hoard their wealth within the confines of the nuclear family. Her marriage wasn’t only an important symbol of gay love’s legitimacy, but a newly accessible tool that straight, white rich people have used for generations to keep money in a select few people’s hands at the expense of the many.

Buttigieg’s candidacy feels similar to me. It’s a significant representational milestone for LGBTQ equality, but one that, behind the symbolism, offers more of the same limited promises hawked by the marriage equality and visibility movements: that one white guy’s win will be a win for us all and that the best — or only — ways for us to gain access to things like health care and education is if we’re legitimized as family members and corporate consumers.

I keep thinking about the now much-memed tweet about how liberals’ response to atrocities like locking people up in concentration camps is to hire 👏 more 👏 women 👏 guards 👏. It seems as if the neoliberal impulse to make the establishment more diverse will always be an easier sell to the mainstream than putting someone in power — of any identity — who wants to dismantle the establishment itself. Unfortunately for queer progressives like me, though, Buttigieg doesn’t really need to care about what we think. He seems to be doing just fine wooing moderate Democrats (gay and straight) who appreciate what little progress he represents, and everything he’s not trying to change. ●