In Ariana Grande’s music video for “Break Up With Your Girlfriend, I’m Bored,” which dropped last Friday, the singer, blonde and bored at the club, watches a couple arriving on the dance floor. The woman, wearing Grande’s signature brunette high ponytail, gestures at her to join them. While Grande makes eyes at the guy, it’s the girl she’s really captivated with; as they stand at the bar, Grande reaches over and strokes the woman’s familiar hair. Later, when Grande meets the couple at a rooftop party, she and her gal pal are matching from head to toe: choker necklaces, little black minis, sky-high brunette ponys. For a second it seems like Grande is looking into a mirror at her own reflection, but no, it’s the woman as her doppelgänger, reflected back at her. At the very end of the video, the throuple wind up in the rooftop pool together. The guy, finally spotting his chance, tugs Grande toward him, but — twist! — the woman grabs Grande’s face just in time and tilts it toward hers. They’re just about to lock lips when the video cuts to black.

Grande makes references to dating herself in the lyrics for “Thank U, Next” — “I know they say I move on too fast / But this one gon’ last / ’Cause her name is Ari / And I’m so good with that” — and the “Break Up With Your Girlfriend, I’m Bored” video takes that trope to its very literal conclusion. The result is a depiction of queer sexuality as a stand-in for self-love and self-empowerment. But Grande is far from the first powerhouse of popular culture to use lesbianism as a visual metaphor, and she definitely won’t be the last.

Just a couple days after the video dropped, at the Grammys (which Grande herself didn’t attend), St. Vincent and Dua Lipa, who’d both take home awards that night, performed a mashup of their respective songs: “Masseduction” and “One Kiss.” Annie Clark as St. Vincent, in thigh high boots and a black unitard, sung that she “can’t turn off what turns me on” before she was joined onstage by Dua Lipa, after which they bizarrely whispered some lyrics from “R.E.S.P.E.C.T.” Lupa, in a monochrome dress lined with gigantic gold safety pins, was St. Vincent’s perfectly complementary doppelgänger: Both wore black, white, and hardware-inspired accessories; both sported the same severe dark bob, though St. Vincent swerved with a side part while Lipa stuck to the center. They touched each other’s bared shoulders, sang seductively face-to-face, and basically eye-fucked throughout the entire performance.

Here, too, seducing a lookalike can be read as a self-empowerment narrative. Last year, Neil Portnow, president of the Recording Academy, which presents the Grammys, suggested that women need “step up” to get recognition in the industry. Lipa made a jab at his expense when she accepted her award for Best New Artist, and other performances and wins that night clearly indicated that women have long since proved themselves to be musical titans. It makes sense, then, that some artists at the ceremony would reprise the well-worn trope of Implied Lesbianism as Loving The Self.

But the lesbian doppelgänger isn’t always readable as a metaphor for self-love. Sometimes, women who look alike — or, in some way, reflect different parts of each other — are arranged as each other’s mirrors in videos and film because that arrangement is aesthetically pleasing, or a commentary on Art with a capital A, or because, frankly, lookalike femmes (if not literal twins) who sleep with each other get straight men off. (There’s a reason “lesbian” was Pornhub’s most searched term in 2018.)

Those uses of the lesbian lookalike tend to be mainstays for male creators, but what happens when the creators and/or subjects of these types of visuals are queer? St. Vincent, for example, has dated women. And when the viewers of these visuals themselves are queer, too? Sometimes, what might be intended to excite straight men can be hot for queer women as well (“Can’t turn off what turns me on”).

These are only some of the questions inspired by the lesbian doppelgänger, which is such a familiar gag in both highbrow and lowbrow culture alike that many queer women are, justifiably, sick of it. They’re sick of the way this trope bowls over less palatable queer visuals involving masculine-presenting people, trans people, people of color, anyone deemed not to have the “right” kind of body; sick of those who appropriate lesbian sexuality for titillation but fail to pay heed to lesbian humanity; sick of mainstream assumptions that female queerness is something narcissistic, for show, or just a phase.

The lesbian doppelgänger can be so frustrating because it can reduce queerness — and queer women’s lived experiences — into a symbol or a fetish. But that doesn’t always have to be the case. In the hands of LGBT creators, versions (or subversions) of the trope can become fascinating meditations on the link between queer identification and desire.

Like other millennial lesbians, I grew up with more representations of bisexual and lesbian women in popular culture than my forebears, but we weren’t exactly rolling in them. When we did see queer woman characters, they were way more likely to dip into doppelgänger territory than not.

Two of my first loves were Marissa and Alex (Mischa Barton and Olivia Wilde) on The OC, whose fraught relationship scored us a precious few key makeouts. Though the two women weren’t identical — they had slightly different cuts to their long hair, which was in slightly different shades of brownish-blonde — they were certainly both thin, feminine white girls. When they finally kissed during the iconic beach scene in the second season, they’re both wearing short dresses — Marissa in white, Alex in black — and their embrace, shot from behind, makes them look like each other’s perfect complement.

There are plenty of real-life lesbian couples who look like Marissa and Alex, but they tend to be overrepresented onscreen. We’re more likely to see couples like Karma and Amy on Faking It, Emily and assorted girlfriends on Pretty Little Liars, or Clarke and Lexa on The 100 than we are Denise and her girlfriend from Masters of None or Big Boo and Poussey with their partners on Orange Is the New Black. And that has less to do with the fact that a masculine-leaning and feminine-leaning pair wouldn’t aesthetically “match” (though they wouldn’t), and more to do with the fact that it’s easier — less threatening — to sell femme lesbianism to the mainstream. Cis and trans butches (Cheryl Dunye in a classic white tank; Leslie Feinberg with a shaved head, wearing a roomy suit; Eileen Myles on the cover of I Must Be Living Twice) are generally relegated to the worlds of queer media.

Femme lesbianism, meanwhile — particularly “fauxmosexuality” performed for the male gaze — has been a recurring pop culture trope. Think about the 2003 VMAs, when Madonna, dressed in all-black, hair in a severe bun, kissed both Britney Spears and Christina Aguilera, who were dressed all in white, complete with matching pearl necklaces and knee-high white boots.

Black or white outfits are common when it comes to the lesbian doppelgänger because she is not always supposed to be a perfect reflection, but rather an alter ego, or one woman who’s been split into two: the timid and the adventurous; the virgin and the whore. So it is in Darren Aronofsky’s 2010 film Black Swan, for which Natalie Portman won a Best Actress Oscar. Her character, the ballet dancer Nina, has sex with a new dancer in her company, Lily (Mila Kunis), who she fears is vying for her lead role in Swan Lake. After being haunted by hallucinations of a doppelgänger, Nina tries to let loose at the bar with Nina. Lily laces Nina’s drink with ecstacy, and later, the two go back to her room, stripping each other to their underwear. Nina’s is, yep, white, and Lily’s is, you guessed it, black. Nina and Lily already looked similar — waif-thin, long brown hair — but after they start having sex, Nina sees Lily transform into someone who looks exactly like her, her true doppelgänger, spooking the shit out of her. Later, Lily denies they ever had sex; it was all in Nina’s head. Lesbianism here operates as a metaphor for the angel and the devil on Nina’s shoulders, two competing, primal drives (literally) fucking with each other until Nina herself is torn apart.

Fauxmosexuality ran particularly rampant in the mid- to late aughts — Katy Perry’s “I Kissed a Girl” came out in 2008 — but the 2003 VMAs were a particular flashpoint. Also performing at the ceremony that year was t.A.T.u., in what would become a major moment in the world of lesbian memes. The video for their 2002 song “All The Things She Said” inspired controversy since it featured the Russian duo kissing in schoolgirl outfits while running around chain-link fences moodily in the rain. For the VMAs the following year, they leaned into the drama, inviting a truly comical number of young women in identical schoolgirl outfits to dance wildly in front of and onstage with them. Lena Katina and Yulia Volkova, in matching mini skirts and pastel tank tops, pranced around holding hands until the explosive end of the performance, when the flood of dancers began ripping off their outfits til they were down to their white underclothes and started kissing in a gigantic lesbian makeout orgy. All the while, newspaper headlines glare threateningly from the big screen: “HIDE YOUR DAUGHTERS!”

If Katina and Volkova were actually in a relationship, that’d be one thing, perhaps, but they later admitted they were just implying one to drum up publicity. In 2014, Volkova declared on Russian TV that she wouldn’t accept a gay son: "Two girls together — not the same thing as the two men together,” she said. “It seems to me that lesbians look aesthetically much nicer than two men holding their hands or kissing.”

Volkova is not alone! A lot of people think that lesbians look aesthetically pleasing together, especially male video and filmmakers.

In Shakira’s 2014 music video for “Can’t Remember to Forget You,” directed by Joseph Kahn, she and Rihanna, who’s featured in the song, roll around together on a black-and-white striped mattress, both wearing black lingerie and black heels. In overhead shots, their bodies are arranged in perfect symmetry. First, they’re turned away from each other, their matching curves accentuated, and in a later shot, they’re face-to-face, legs intertwined in a near-scissor, while they stroke each other’s legs. It’s one of the rare times they’re actually looking into each other’s eyes; for the rest of the video, they’re smoking cigars or leaning suggestively on each other’s shoulders while staring at the camera, performing for its gaze.

Similarly, in the last scene of Park Chan-Wook’s otherwise excellent 2016 erotic thriller, The Handmaiden, the two main characters, Sook-hee (Kim Tae-ri) and Lady Hideko (Kim Min-hee), start to have sex while balanced precariously on their knees, facing each other, naked legs scissored. It’s a visually rich tableau, the kind of thing you’d want to paint, but not really the kind of thing you’d want to emulate — these women, perfect reflections of each other, look lovely, but they sure don’t look very comfortable. That image echoes similar ones in Abdellatif Kechiche’s infamous sex scene in Blue Is the Warmest Color (which was reportedly shot unethically): two women scissoring and 69ing in impersonally wide shots, their young, beautiful bodies — which are graphically matched with statues in art museums at other points in the film — arranged as matching masturbatory tools (but artfully!!!). They are a set of beautiful and inspiring objects.

The lesbian doppelgänger, when not outright offensive, is often just a really boring creative choice. But it’s a lot of fun to see queer creators reclaim and subvert the trope.

In a season 2 episode of Broad City, Ilana starts hooking up with a woman named Adele, played by Alia Shawkat (in real life, both actors have frequently been compared to each other), with whom she has her “first simultaneous orgasm.” It’s not until Adele is going down on her and Ilana sees her own face between her legs instead of Adele’s — a Black Swan gag — that she gets freaked out. “It’s too weird!” Ilana says, sitting up. “I don’t want to freak you out too much, but we look exactly alike.”

“Yeah, no shit,” Adele says. She figured that’s why they started hooking up in the first place — it’s hot, like hooking up with yourself! “Nobody knows our bodies the way we do,” Adele adds, immediately finding Ilana’s G-spot and making her temporarily go blind.

The L Word also gave us some delightfully goofy iterations of the trope. In preparation for the reboot later this year, I’ve been rewatching the Showtime series in bits and pieces, and it’s nice to be reminded that for all the shit we give it, this show can really have its wonderful moments. I just dipped into Season 5 for the incredible pot brownie episode — Dawn Denbo confronts Shane about sleeping with her lover Cindi! — which is around the time Jenny (Mia Kirshner) starts seeing Niki Stevens (Kate French). The increasingly off-the-rails Jenny has been put in charge of directing the film adaptation of her autobiographical novel, Lez Girls, and Niki is cast as its difficult-to-please star; she’ll be playing Jenny’s character, Jessie. The recalcitrant Niki softens when she and Jenny strike up a friendship, goofing off on set and complimenting each other’s clothes. When they eventually hook up, it’s an extremely sweet scene, the two of them drunkenly crawling around on the floor of a closet and giggling all the while.

Season 5 is the season of the doppelgänger. While Jenny rather literally begins to date herself, her assistant and protégé, the secretly psychotic Adele, is gunning for Jenny’s career in an L Word spin on All About Eve. The Adele plotline is kinda bonkers, and so, too, is Jenny and Niki’s eventually — but at the beginning, at least, they’re annoying yet lovely.

Niki and Jenny’s relationship highlights the ways in which lesbian relationships can indeed be, at least in part, about the way we identify with one another. For many of us before we came out, we weren’t quite sure whether we wanted to be the girls or women we admired, or whether we wanted to be with them. Sometimes, self-recognition and desire isn’t necessarily a one-or-the-other kind of thing; it can be a complicated cocktail.

Niki and Jenny, each other’s more literal doppelgänger, take enormous pleasure in the things they have in common, the created character they share. Any femme who’s dated another femme knows the delight of pillaging each other’s closets, of doing each other’s makeup, of sharing the same beautiful, feminine world.

I think that’s the case for a lot of queer women, regardless of gender presentation. Some of our first loves were with girls in whom we saw pieces of ourselves: girls who liked the same things, who had similar ways of engaging with the world. And some of those pleasures of identification can carry us into our adult relationships. Now, I’m dating a masculine-of-center nonbinary person; sometimes we’ll accidentally show up to the lesbian bar in the same Carhartt beanies, but we definitely don’t look much alike. Still, we share what it’s like to grow up assigned-female; we share what it’s like to get a period (often, horrifyingly, at the same time); and, perhaps most of all, we’re both queer — with queer friends, queer sensibilities — which means we have a shared culture and language.

Andrea Long Chu, in her widely praised essay for n+1 last year, On Liking Women, perfectly captures that swirl of identification and desire, in her case as a trans woman:

I doubt that any of us transition simply because we want to ‘be’ women, in some abstract, academic way. I certainly didn’t. I transitioned for gossip and compliments, lipstick and mascara, for crying at the movies, for being someone’s girlfriend, for letting her pay the check or carry my bags, for the benevolent chauvinism of bank tellers and cable guys, for the telephonic intimacy of long-distance female friendship, for fixing my makeup in the bathroom flanked like Christ by a sinner on each side, for sex toys, for feeling hot, for getting hit on by butches, for that secret knowledge of which dykes to watch out for, for Daisy Dukes, bikini tops, and all the dresses, and, my god, for the breasts.

Wanting to date someone much like yourself could easily be construed as a kind of narcissism, and indeed it has been by anti-gay bigots. But some theorists argue queer people should lean into that narcissism, rather than attempting to assimilate into a hetero-patriarchal world. In his 2004 polemic, No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive, Lee Edelman makes the case that the symbolic innocent Child, “in need of protection, represents the possibility of the future, against which the queer is positioned as the embodiment of a relentlessly narcissistic, antisocial, and future-negating drive.” He argues that queer people should “accede to their status” as figures of negativity, rather than becoming rank-and-file members of the social and political order.

Olu Jenzen, in a 2013 article published in the Journal of Lesbian Studies, also argued in favor of queer narcissism. “Revolting Doubles: Radical Narcissism and the Trope of Lesbian Doppelgangers” discusses lookalike narratives that have been unpopular among queer audiences for their perceived reductiveness — like Nina and Lily in Black Swan — and argues in favor of their power as images, ones to be “enjoyed as a subversive statement of highly self-referencing, auto-erotic, and self-sufficient economy of desire.” Heteronormativity is structured by promoting the desire of difference — men are from Mars, women are from Venus, etc. — and radical queer narcissism, Jenzen writes, is a “refusal” of heteronormativity’s “underpinning organization of desire and identification as exclusionary.”

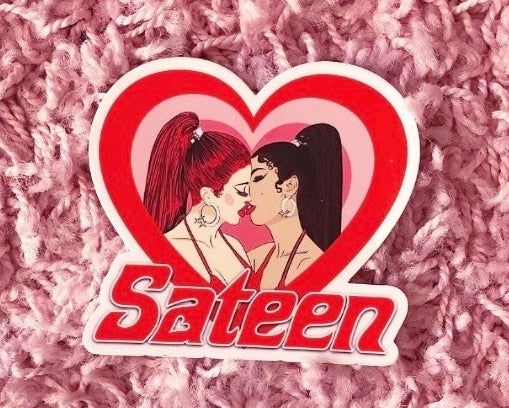

When I think about the potentials of radical queer narcissism — loving our queer selves, loving our queer partners, even in a world that tells us so often to hate ourselves — I think about a couple like Ruby and Queenie, the Brooklyn disco glam pop musical duo who told i-D a few years ago that “with narcissism on the rise,” drag is the perfect art form: “You can transform yourself into your own inspiration.” Once known as a “hetero drag couple,” a characterization they never felt fit their identities, Ruby has since come out as trans, and now, Ruby and Queenie perform together as Sateen, with songs like the lesbian power anthem “Lightning and Thunder” and the ode to femme empowerment, “Finer Things.” On their Instagram account (which just hit 100K followers), the couple are often wearing matching hairstyles and lingerie, promoting images of high-femme lesbian love. Some of their merch includes a visual of their logo with the two women kissing in matching high ponys — one red, one brunette — an image of lesbian lookalikes that evoke Ariana Grande and her doppelgänger. I prefer Sateen’s version, though. They’re real. ●