Marie Calloway doesn’t want to participate in this profile.

For months, the introverted writer has known that I was working on a story about her and her writing — as well as the often loathsome reactions her work garnered a little less than a decade ago. I tried reaching out to her through her friends, her agent, her former publisher, and she politely declined every time. It didn’t seem like Calloway was displeased, just bemused and evidently uninterested in being directly involved.

“I think she thinks it’s funny to be absent in a profile like this,” Annelise Ogaard, a filmmaker and Calloway’s friend, told me in an interview. They’ve been friends since middle school, having found each other on LiveJournal at 14; a lot of the people in Calloway’s life encountered her on the internet as teenagers, long before she became a writer and a symbol for oversharing. “I really think the driving motive here is her loopy sense of humor.”

But if Calloway had suddenly become convivial and media-friendly, I guess I’d be disappointed. It just wouldn’t make sense given the nature and tone of her brief public career, one that started around 2010 and ended abruptly around 2016. Part of her appeal — even when she was still on Facebook and doing readings in independent bookstores throughout New York — was that she wasn’t very big on explaining herself. When she deleted her once-prolific Tumblr account a decade ago, her reasoning was brief: “Dislike being ‘watched,’” she wrote.

If you were on the internet in the 2010s, you’re probably aware of Calloway’s work, even if you can’t quite remember the specifics. Her writing appeared on websites like Thought Catalog and Vice, which were dedicated to archiving the feelings of upwardly mobile white millennials. Then in 2012 came the story that brought her both notoriety and ridicule; “Adrien Brody” was published online by Muumuu House, a small press founded by alt-lit writer Tao Lin in 2008. (The actor Adrien Brody has no apparent link to the piece.) In it, Calloway describes meeting a man online and sleeping with him. He’s significantly older than her, has more power in their dynamic, and has a girlfriend. “I know you said you don’t want me to say this,” “Brody” — a pseudonym seemingly selected because of the absurdity of naming him after someone so famous — tells her at the end of their encounter, “but you will connect with someone one day. It’s just not going to be me.” Amidst the female personal essay boom of the 2010s, the lengthy piece went viral.

It wasn’t tough to figure out who Calloway was writing about. According to the Rumpus, the story had previously been published on her now-deleted Tumblr and used the name of a real literary figure, Rob Horning, then a senior editor and now the executive editor at the New Inquiry; at least in New York media, he might never be able to shake the association completely. Horning has kept quiet publicly about the essay, which paints him as yet another man with an inferiority complex who cheats on his girlfriend with a much younger woman.

“Adrien Brody” sparked a debate about the ethics of outing someone’s bad behavior, the value of confessional writing, and whether Calloway was a good artist or just a pretty-girl provocateur who knew that writing graphically about cum would get her some attention. “It’s always been acceptable for men to completely consume young women for their art,” Ogaard said. “But Marie writes about this relationship with this man and everyone’s like, whatever happened to discretion?” (Horning did not respond to my multiple requests for comment.)

There were stark contrasts between the prevailing arguments about her: Calloway was either a calculating Lolita-in-training who exposed a man’s legal but distasteful indiscretions for her own professional gain, or she was a fawn among sharks, not understanding how she was being taken advantage of by the men in her life. “With writing like Ms. Calloway’s, it’s tempting to believe that there is some sort of feminist impulse at work, that she derives power from humiliating men with her sexuality, the same tool they used to objectify her,” Kat Stoeffel wrote in the New York Observer in 2011. “But most of her subjects — she’s done it more than once — were complicit, willing, and even flattered.”

Some people (like myself) found her work refreshingly honest and the writing crisp and memorable. Others (also like myself) felt troubled by how much of herself she was exposing, sometimes literally, like the photos of her cherubic face and near-naked body that appeared in her book. Her writing also served as an opportunity for some to scold her under the guise of caution. “It does no favors to young female writers to convince them that they are courageous voices in the wilderness for dedicating their talents to writing stories that are received as lurid, not literary,” Hamilton Nolan wrote in a post about Calloway on (the original) Gawker. “Let’s all shut up more in 2012.”

Calloway’s work was considered “alt-lit,” a designation once disparagingly and condescendingly described as “Asperger’s realism” for its unemotional approach to fraught relationships and personal stories. Influenced by the platforms and parlance of the internet, alt-lit was an offshoot of the genre of semifictionalized autobiography called “autofiction.” Autofiction writers like Sheila Heti, Ben Lerner, Jenny Offill, and Karl Ove Knausgaard later received significant praise in the literary world for their work, all very different in content but similarly marked by their emotional disconnection and spare, almost poetic, prose. But in her time, Calloway was a unique lightning rod, and she wasn’t given much time — or room — to grow as a writer. Reviews of her work were barbed and personal. “There’s literary criticism, and then there’s ‘shut the fuck up,’” Ogaard said. “The backlash wasn’t just to her writing. It was to her as a person.”

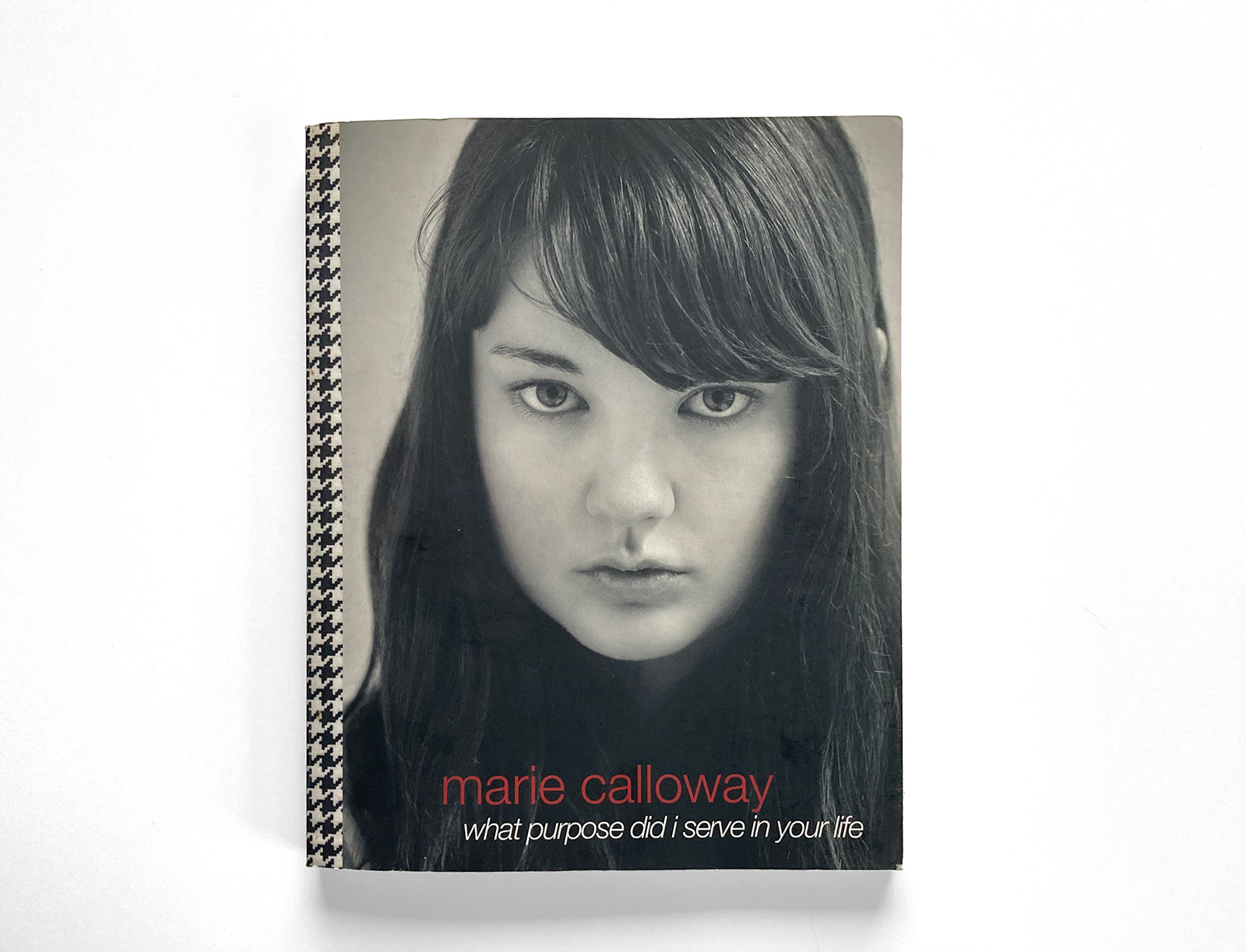

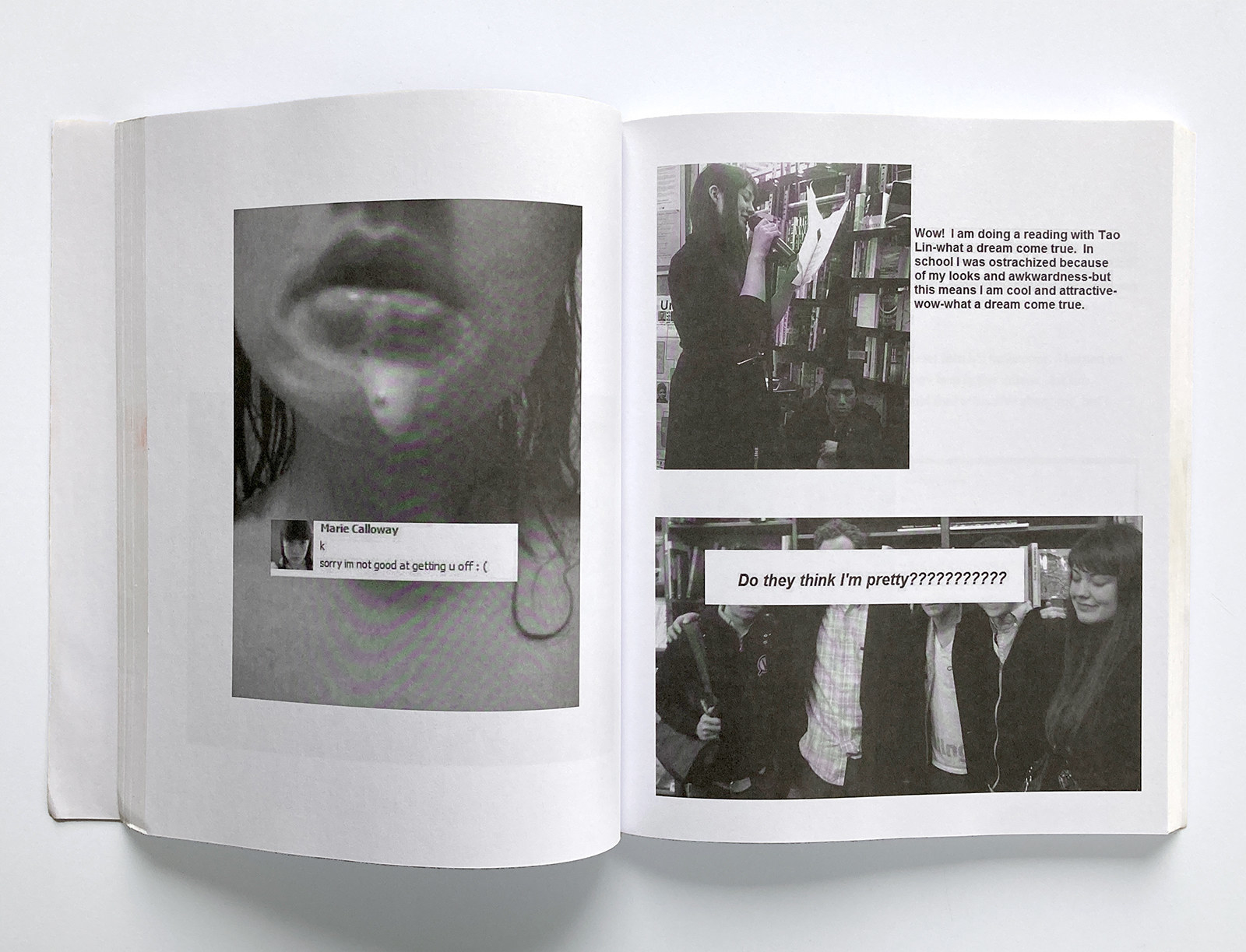

Calloway’s one and only book came out in 2013, titled what purpose did i serve in your life (styled in lowercase, as was de rigueur in alt-lit). It was a 240-page paperback the size of a spiral-bound Mead notebook, the front and back covers plastered with moody black-and-white shots of Calloway’s unsmiling gaze and "Mona Lisa" eyes. The book is part confessional essay collection and part Tumblresque anthology of text and selfies, covering sex work, mentorship, the male gaze, literary (and personal) criticism, and BDSM.

In the first essay, “portland, oregon 2008,” Calloway writes about losing her virginity in a way that reads as both heartbreaking and intense and yet completely divorced from the traditional sentimentality of your first time. “In the middle of the night I got up and went into his bathroom. I turned on the light in the bathroom and stared at my face in the mirror,” she writes. “For ten minutes I tried to see what someone could find attractive about me, but I couldn’t find anything.” “Adrien Brody” is reprinted in what purpose did i serve in your life; there are also screengrabs of Facebook conversations between Calloway and men describing their fantasies of pissing on and hitting her. “Mew are you going to make me cry,” she asked a man over text in October 2012. “Yes,” he replied. “It will be glorious.”

Published by Tyrant Books, an independent press run by Giancarlo DiTrapano up until his death in March 2021, the book was a modest success by its standards — there was virtually no marketing other than social media word-of-mouth and DiTrapano’s claims that printers had refused to print the book because of its explicit content, which was a pretty good way to drum up controversy. (Fat Possum Records, which now owns half of Tyrant Books, did not have comment about the claim.)

According to Tyrant, the book sold around 5,500 copies. The book caused so much uproar that Calloway was reportedly invited — and then uninvited — to appear on Dr. Phil. (The person who could probably best contextualize what made Calloway’s writing so affecting is no longer around; DiTrapano was a fierce defender of hers, both personally and professionally.)

In 2016, Calloway published a piece of fiction in Playboy about a young woman’s encounters with married men called “Insipidities.” It’s the last thing she wrote for public consumption, and as far as I’m concerned it’s her best work; it shows the clarity about sexual politics, power, and the literary industry that she was building toward in her book. After the story’s publication, she basically vanished. Her Facebook page is gone, and her Instagram has disappeared. The young woman who once wrote, “To be dominated and degraded was what I wanted. Sex is just a way to get those things,” has gone silent, a true literary recluse.

If someone wanted to build a young woman specifically for the purpose of being hated by the internet, Calloway was what they would’ve wrought. She and I are the same age, and, while stylistically our work is different, I always felt a little envious of how dynamic and divisive her work was. While some people found her writing evocative, she was more often the subject of sneering attacks. How could someone handle that much vitriol directed their way? Every so often, I wonder what it would take for Calloway to come back to the world she left behind. But then again, it feels perfect that someone who captured the attention of the internet would decide to bail on it completely.

Despite Calloway having once been an extremely online cult favorite, there’s very little publicly available about who she actually is. Her real name isn’t even Marie Calloway; that’s a pseudonym she developed in her early 20s when she started blogging. Her real name, it’s rumored, is somewhere in the first edition of her book. Through conversations with her friends and literary contemporaries, I’ve found out that she’s originally from Las Vegas, and that she relocated to Portland, Oregon, after high school. From there, she floated around — to Chicago, London, possibly back to Portland for a while, then to New York the year her book was released.

She’s probably 30 or 31. No one seems to know for sure because no one seems to know Calloway’s birthday. Rachel Rabbit White, a writer, longtime friend, and erstwhile lover of Calloway’s (White told me they had matching necklace vials filled with each other’s blood), told me even Calloway herself doesn’t. “We both spent so long in [sex] work lying about our age that she would forget,” White told me over the phone. “She decided she was going to be a Scorpio but then forgot her actual sign.” According to White, Calloway now lives in Manhattan, recently got married, is studying Japanese, and just enrolled in massage school.

People I spoke to told me that Calloway was painfully quiet and deeply awkward in person. Her work does betray this; she always portrays herself as an ugly little gnat bothering the literary elite or crying in a man’s bed as he emotionally rejects her. “That was her big issue at the time. She was like, I’m too Aspie, I’m too Aspie,” White said. “She did have a hard time socializing and hanging out with people.”

Calloway’s work was niche. She might have been at the forefront of alt-lit, but she was never reviewed by the New York Times. Her book was a success for Tyrant Books, but it probably wouldn’t have been distributed by any of the mainstream publishers, even today. Yet her influence is present in the personal essay genre, in memoirs, in fiction about troubled young women. Her sparse prose and unflinching unpleasantness is no longer unusual; Melissa Broder’s Milk Fed, Halle Butler’s The New Me, or Darcie Wilder’s Literally Show Me a Healthy Person all belong to her lineage. Even literary megastar Sally Rooney’s work betrays flashes of Calloway in the hornier passages of her three bestselling novels.

And, of course, Kristen Roupenian’s mega-viral short story “Cat Person” inspired a similar furor to Calloway’s work. Published in the New Yorker in 2017, it too was about a relationship between a younger woman and an older man. (“I think there’s this moment when ‘Cat Person’ came out where people kind of realized that Marie was influential,” said Monika Woods, Calloway’s longtime literary agent.) Roupenian was also criticized for seemingly having drawn from a real person’s life for her story. In July of this year, Alexis Nowicki wrote a story for Slate about how she believed “Cat Person” was based on her former relationship. “What’s difficult about having your relationship rewritten and memorialized in the most viral short story of all time is the sensation that millions of people now know that relationship as described by a stranger,” Nowicki wrote. (The Slate piece included Roupenian’s response to Nowicki’s claims, and Roupenian subsequently published her own essay about what drives her to write.) But isn’t that what all good writing, fiction or not, is — a story that feels so familiar and connects so deeply that it feels like it was written specifically for you?

“I do think her work looks back at you,” said Brandon Proia, an editor at the University of North Carolina Press and an old acquaintance of Calloway’s. (According to him, they met on OkCupid.) “Which is why it’s hard to duplicate. It’s an inimitable thing. She was so fucking ahead of her time.”

Calloway sparked an online dialogue about ethics in personal essay writing well before the Babe.net essay about Aziz Ansari during the height of #MeToo. Her work was about sex, sex work, and sexuality, which rankled plenty of readers. “I don’t understand how it got so dismissed,” White said. “People would be like, we know this story. Well, do we? Name another great American sex work novel.”

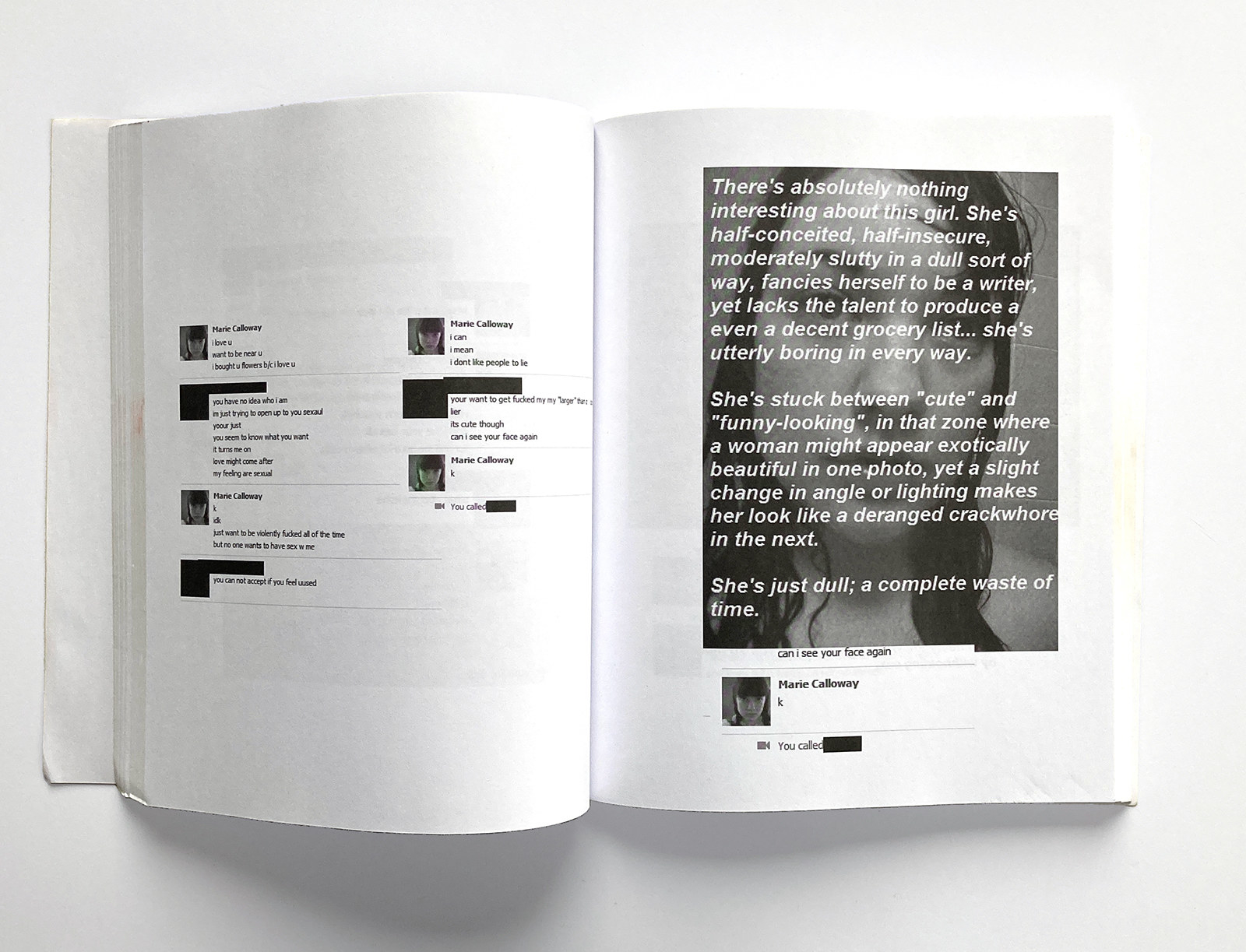

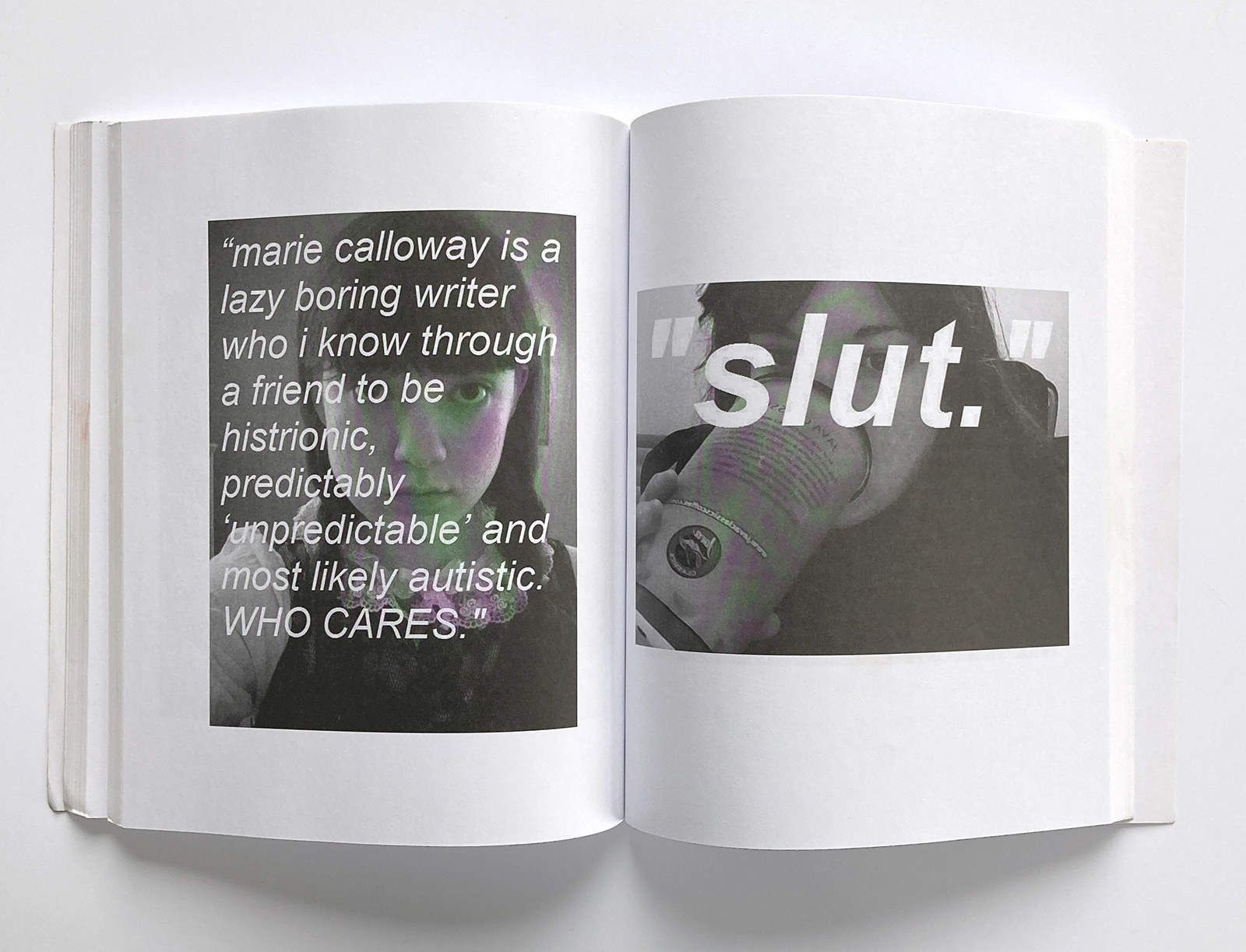

In what purpose did i serve in your life, Calloway seems very aware of how people have judged her and her work. Throughout the book are photos of her face, her pixelated naked body, her drinking a coffee, all overlaid with critiques. “There’s absolutely nothing interesting about this girl,” says one, printed on an image of Calloway in the shower. “She’s half-conceited, half-insecure, moderately slutty in a dull sort of way, fancies herself to be a writer, yet lacks the talent to produce even a decent grocery list.” Another is much more succinct: “Slut.” Calloway wasn’t writing Letters to Penthouse, but a lot of reviews treated her like she was. “For the book’s first half Marie’s fragility carries the text,” Publishers Weekly wrote, “but her voice grows tiresome as she moves from selling sex to becoming a published author.”

Calloway was also perceived as having ridden on the coattails of another literary man rather than stewarding her own critical success. What purpose did i serve in your life contains a very thinly veiled essay about Tao Lin called “Jeremy Lin,” which was also originally published online. (Lin has not disputed the connection. “I really like reading about myself from other people’s perspectives,” he told me in an email.) In it, she tries to impress a vaguely powerful but obnoxious male writer and editor in New York. “That’s the book’s central dynamic, powered always by the narrator’s age,” Michelle Orange wrote in Slate. “Men respond to Marie. This is both what happens in these stories and what she tells us herself.”

Around the time of the book’s publication, there seemed to be some belief that Lin was Calloway’s literary Svengali. Others thought she was mimicking him and his disaffected demeanor, because that’s what everyone else was doing. “If you weren’t there at the time, it’s hard to remember what a huge presence Tao Lin was,” White said. “It was wild. Tao would walk into a party and suddenly everyone would have slumped posture and be speaking in a whisper like he did.” In “Jeremy Lin,” he comes off as withholding, never really telling Calloway what he thinks about her, and she desperately yearns for his approval. These days, Lin is effusive about Calloway’s work. “I was amazed by the combination of the focused and original story and content, the earnest and melodramatic tone, and the straightforward and unclichéd writing style,” he said.

Lin continues to publish and get good reviews, but he’s far less influential than he once was. In 2014, a former partner accused him of statutory rape and emotional abuse on social media, a year after his most famous book, Taipei, was released. (He has never been charged with a crime.) “I’m not trying to start any wars with the alt-lit people, but a lot of them were disgraced,” Proia said. “Her work stands up in a way that seems more relevant than a lot of the stuff that happened back then. The sometimes-submerged-but-nevertheless-there politics of what she was talking about and working through was there from the start.”

Not only was her writing seen as a little grotesque and unflinchingly sexual, it was about sex as work as well, sometimes titillating but also depressing and discomfiting. She framed her clients as sometimes preening, pathetic little men, and she didn’t enjoy the sex. She spent her money on things people generally consider frivolous, as if a sex worker isn’t entitled to a new lipstick or a pint of beer like everyone else is. In her own stories, she was sometimes flighty, anxious, inconsistent, unmanageable, and almost aggressively self-destructive. Calloway’s departure from public life is a shame on a few fronts, but that’s namely because she’s missed out on a unique moment of sex positivity, one that she helped create 10 years ago. “People called her ‘attention-seeking.’ Well, if you publicly create art, of course you’re seeking attention,” Ogaard said. “They weren’t mad she was seeking attention. They were mad that she got it.”

In hindsight, the hatred for Calloway’s work was inevitable if disproportionate to her apparent transgressions. She wasn’t mainstream, she wasn’t rich, she wasn’t cruel, and she had very little power. Still, the reviews and public discussions around her book were vicious and often angry. How dare this young girl sell her body to men and then write about it as if we care?

Even when reviews were complimentary, they were still a little leering and sometimes derisory. In 2013, Esquire writer Stephen Marche called her book “a minor masterpiece” but also wrote, “Personally, I find it hard to see how having your face come on by an older man constitutes an act of female empowerment, but of course I am a man.” Nearly all of Calloway’s readers — regardless of gender — treated her like a zoo animal, something to be gawked at. “On the cover of my book, I wasn’t wearing makeup and I didn’t style my hair,” Calloway told Michael Musto in Gawker in 2013. “Some people have commented on how ‘ugly’ the photo is. When people talk about my supposed beauty, it seems almost accusatory, not so different than when MRA types talk about female privilege.” (Among Musto’s other questions: “Do you wake up horny every day?”)

“There was this male fixation on the young woman. I think a lot of those people had a problem with Marie because she was a young woman and she was writing about her experience,” Ogaard said. “She was a transgressive writer, whereas they would borrow this take, this pedophilic, gross lens. They didn’t have any real perspective. Their interest in women was like a fetish. They weren’t interested in women. They were interested in young girls.”

Writer Sarah Nicole Prickett was also critical of Calloway at the time. Prickett and Lin interviewed each other in 2013 after the release of what purpose did i serve in your life. At the time, Prickett was downright cold on Calloway’s work. “Maybe she’s a writer. I don’t think she’s doing anything else,” Prickett said in the interview. “I will say that she seems to be a slightly better writer than sex worker.” But Prickett had actually pulled the “Maybe she’s a writer” line from a scene in Calloway’s book: A friend tells Calloway that she has to stop thinking that sex is the best thing she has to offer when in reality it’s her writing. “An interesting choice on my part to take something she said about herself and repeat it in a kind of perverted, contemptuous tone,” Prickett told me over the phone a few weeks ago. “It’s something that I said about myself.”

Calloway would have been around 22 at the time, and Prickett in her late 20s. But Prickett was arguably the more established writer, which makes the comment seem even harsher. “I think I had more conservative values at the time, maybe a conservative idea of what literature should be, and I was wrong about a lot,” Prickett said. After I contacted her for this story, she said she had reread Calloway’s book and felt at least a little regret. “I don’t know whether I identified with Marie but, having been recently Marie’s age, there’s nothing more embarrassing than the recent past,” she said. “When you’re 26 and think about who you were at 23, it’s a little repulsive. I think I took it personally whenever I saw a young woman writer who I felt was not being taken care of properly. Obviously I wasn’t really talking about Marie, was I? I was just talking about myself.”

That might have been Calloway’s greatest gift as a writer. Reading her work felt a little like reading snippets of your own diary. Even if you were nothing like Calloway, the feelings of alienation, inferiority, and the all-consuming need to be desired were so familiar, and that unabashed vulnerability got under people’s skin in a very specific way. “I often feel like other women attack my work to ensure a distance,” she told Vice in 2013.

Many of Calloway’s critics were women, and the arguments against her were often cloaked under the ideals of feminism: Here was another young woman offering herself up to the male gaze. It’s an interpretation that removes a lot of her own agency. Couldn’t she have just been writing what she wanted, the way she wanted to, about the things occupying her mind at 22? “I feel that especially hurt, to have so many women detractors who were saying that she was selling her sexuality, when really what she set out to do was explore female sexuality in an honest way,” White said. (Few of Calloway’s former critics spoke to me for this story, and the ones who did were all women. The many men I contacted who had mocked and derided Calloway’s work ignored my requests for comment.)

When what purpose did i serve in your life was released, I’m sure I was cruel about it too. I’m sure I denounced her portrayals of sex as gimmicky or that I winced at those private messages where she purrs “mew” to the men trying to employ or court her. But in retrospect, I think my critiques stemmed from jealousy or maybe the desire to protect someone who seemed a little bit like me. “I thought she needed to be protected from herself,” Prickett said. “I was probably just reaching the age when I was starting to regret writing things. Maybe I thought it was too ephemeral and regrettable. I think I was saying things about Marie that other women three years older said about me. I was just taking my place in the chain.”

It’s been eight years since Calloway published a book, five since she published work online. Her agent and friends assure me that she isn’t publishing under a pseudonym, and that she currently only writes for herself.

Her work exists in the specific paradigm of the 2010s; to imagine her in contemporary terms is to ruin whatever legacy she’s left behind. “You can’t imagine Marie Calloway [saying], ‘Take my three-day online Zoom workshop!’ You can’t imagine Marie with a GoFundMe page, making sweeping generalized statements about sociopolitical conflicts,” said Scott McClanahan, a fellow Tyrant Books author. “Wouldn’t it be funny if Reese Witherspoon signed off on this book? Unleashing that on the moms of America!”

While Calloway repeatedly declined my requests for comment through her agent and White, some of her friends were confident that I’ll hear from her after this story is published. (This seems like a pattern — even Calloway’s critics have heard from her, privately, over the years. Some told me they have even become friends with her.) Meanwhile, every source I called had a story to tell me, one that Calloway had suggested they recount. “This is probably what she wanted me to talk to you about,” Proia said with a laugh, launching into an anecdote about how Christian printers refused to reproduce the book. “She actually is her best interpreter.”

“It’s too early to say whether she will matter,” Prickett wrote in Thought Catalog in 2013. At the time, this was true. Who knew whether Calloway would be a flash in the pan or whether her work would have a long-term impact? Her milieu was pretty small. “It felt like you were publishing for your friends. There was no chance of one of us being in the New Yorker,” McClanahan said. “We fucking hated the New Yorker. And now the New Yorker has published very Marie Calloway–esque stories.”

But of course Calloway mattered. You can see her influence in the way personal writing on the internet has become a cottage industry, and how it has gone from something people considered a passing fad (women talking about themselves?) to its own subgenre. You can see it in how the public discourse around sex work has started to shift away from judgment toward compassion.

One thing Calloway likely understood earlier and better than almost anyone else was the cruel tides of the internet. And after experiencing intensely corrosive blowback, she simply decided to leave. Like everyone, I think about logging off most days. The more I stare at Twitter and worry about my least generous critics, the less I feel capable of cogent and publishable thoughts. I also think a lot about “Insipidities,” her last short story. It’s the most mature and self-aware she’s ever been in print. “New York is hideous, with gray dilapidated buildings and filthy streets mottled with failed asphalt and garbage heaps,” she writes. “And the people are even worse. It’s like living inside an eternal cocaine comedown. Why does anyone live here?”

It betrays the kind of cynicism that can only come from receiving endless virulent criticism from your peers. But, according to her friends, Calloway’s absence from the literary world may not be permanent. “I know she’ll write. I know she’ll publish again,” Ogaard said. “It’s a matter of when. It’ll happen when she’s ready.” But a version of the future where she never reemerges is pretty compelling too. It would be satisfying to keep pristine the memory of Calloway’s brief and fiery career, someone whose insights were so ahead of her time, trapped in internet amber. Why make yourself available for a new round of cruel takedowns about your work and your body? “I don’t know that she’ll ever come back,” White said. “If I were her, I don’t know that I’d want to either.”

The tragedy is that there is probably no one better suited to speak to the misery of the online feedback loop than Calloway. She was an early victim of the worst of the internet, so who would be better to contextualize it for the rest of us still trapped here, hoping to escape? But Calloway owes us nothing, especially after giving so much and getting very little in return. I’d love another essay, another story, another Tumblr post, but I know we don’t deserve it. Her victory is in her retreat. ●