It isn't easy to make Khizr Khan say the words "Donald Trump.” He goes out of his way to change the subject or starts his sentences with "without naming names” — which is surprising, in part because Trump is the reason why most people know who Khan is. You may not recognize his name, but you likely remember the image from last June of a sixtysomething-year-old Pakistani-American Muslim man standing at the podium of the Democratic National Convention, back when some believed we’d finally have our first female president. With his wife, Ghazala, by his side in a powder blue salwar kameez, Khan pulled out a pocket-sized copy of the Constitution and waved it at the audience as he addressed our president to-be.

“Donald Trump, you are asking Americans to trust you with our future. Let me ask you: Have you even read the US Constitution?” he said as he held it in the air like a lit torch. “I will gladly lend you my copy. In this document, look for the words ‘liberty’ and ‘equal protection of law.’”

Khan was invited to the DNC not just because when he speaks, he does so with a kind of conviction and kindness that makes you want to follow him wherever he goes, and not just because his story of immigration and sacrifice and perseverance is truly the stuff of uplifting movies, and not just because, as a Muslim lawyer, he was uniquely suited to address Trump about his campaign promises. It’s unavoidable to point out that the Khans were invited to the DNC, in large part, to talk about their son, Captain Humayun Khan, who was killed while serving in Iraq in 2004.

This fact made it all the more egregious when Trump began attacking Khan and Ghazala after the speech. “I’d like to hear his wife say something,” Trump said, later suggesting that perhaps Clinton’s speechwriters wrote Khan’s speech.

Khan’s sons had initially told him not to make the speech, that nothing good would come of it, but he did it anyway in the hope that it would help combat some of the ugliness that came from the 2016 campaign. Maybe with a few hundred words, he thought, Khan could get Americans to hear his assessment of the president-to-be: “You have sacrificed nothing and no one.” The audience stood for nearly his entire speech, cheering raucously at the end of every sentence, some crying. There was tangible impact, too; after Khan’s speech, pocket Constitutions became the second best-selling book on Amazon.

But like so many other scandals throughout Trump’s campaign, Trump’s attacks on the Gold Star family didn’t seem to matter in the end. Khan watched the election results in New York, optimistic that Clinton would win until close to midnight. “We were totally disappointed and disheartened and couldn’t believe it,” he recently told me over the phone. “I have two granddaughters. Every time I would speak with them, I’d say, ‘See? We will have a woman president also,’” he said. “I was kind of deprived of that conversation. It meant so very much to us. To me, especially.”

These days, Khan can’t always avoid mentioning the president; just this week, he described Trump’s actions as “selfish and undignified” after he neglected to call the families of soldiers killed in Niger. But often, when you bring up Trump with Khan, he demurs and instead talks about the systems that brought Trump to power, about how division is a temporary anomaly for the United States, or simply starts his sentences with “Without mentioning any names.”

“I am positive this division will go away. That’s why I don’t talk much about Trump, because this is a momentary difficulty our country is having.”

Khan’s new book, An American Family: A Memoir of Hope and Sacrifice, is part autobiography, part civics lesson (the end pages are photocopies of Article VI, Amendment XIII and Amendment XIV of the Constitution, with Khan’s scribbling, underlining, and highlighting), and part patriotic message about the goodness of all Americans. It’s also a deep dive into how a poor Muslim Pakistani boy made it to the US and became a symbol of the resistance against a sexist, race-baiting president who tried to ban immigrants from a number of Muslim-majority countries. But in the book, which comes out next week, Trump hardly garners a mention until the very end.

You might think that Khan would feel deeply disappointed in — or even hopeless about — his adopted nation after watching just under half of the US electorate ignore his clear warning about exactly who Trump-as-president would be, and elect him anyway. But when we spoke, he always drove his answers back to the point of both his book and his public persona: America is worth fighting for.

“I am positive this division will go away,” Khan said. “That’s why I don’t talk much about Trump, because this is a momentary difficulty our country is having. Within the DNA of this nation is unity, solidarity. I am a testament to that sentiment of the nation.”

Even if that optimism sometimes seems unearned, even if his hopefulness sometimes feels like the exact thing a first-generation immigrant might say to their ungrateful, Americanized child — I suffered worse than you ever will — and even if it sometimes feels like Khan is too generous to a country that is mired in its divisions, it’s still so easy to listen to his stories of patriotism and unity, and really, truly, believe that his is a world we could all one day live in too.

Khizr Khan talks a lot. His schedule is packed with live speaking engagements and interviews — when we spoke on the phone this week, the second of two interviews, he was on his way to New York, then to DC, then to Anaheim to speak to health care workers, then back home to Charlottesville, Virginia, on a red-eye, only to go back to New York and Philadelphia the following week. Khan speaks to Muslim organizations like ISNA (Islamic Society of Northern America); he spoke this month at a gala commemorating Holocaust survivors in Boston; he speaks to universities and high schools and churches, to HBO and The Atlantic and, now, BuzzFeed News.

When we met in New York in early October, at his publisher’s offices, Khan exuded gratefulness. He thanked me endlessly for speaking to him, he got up from his chair when I did, shook my hand with both of his. In a follow-up call, he checked to make sure that I “made it back home.” Next to Ghazala at the DNC, he looked towering, but in reality, he’s small in stature, quiet. His aura is academic, like a patient college professor explaining something very basic about democracy to you.

An American Family starts all the way at the beginning, when Khan was a young boy living in Pakistan under martial law in the ‘50s and ‘60s. (Khan was a child when the Pakistani coup d’état occurred; a self-appointed president did away with political parties, outlawed large public gatherings, arrested opponents, and controlled the media. Khan recalls vicious police brutality, revolutions, corruption, and chaos.)

“I had been in awe of this country’s values since I was in law school, 22 years ago. I read the Declaration of Independence,” he told me. Khan talks often about having an intimate understanding of what it’s like to live without civil rights, of feeling like your humanity was being taken away. He described himself thinking, “I wish I could live in such a place where all these rights and dignities are guaranteed.” But Khan was the eldest of 10 brothers and sisters, extremely bright but not particularly well off. “I had to come to the United States gradually,” he writes in the book.

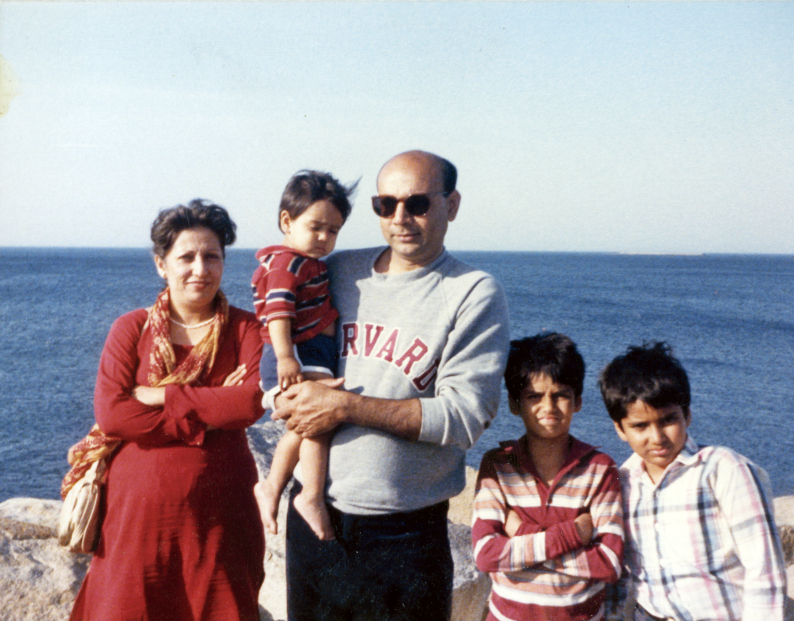

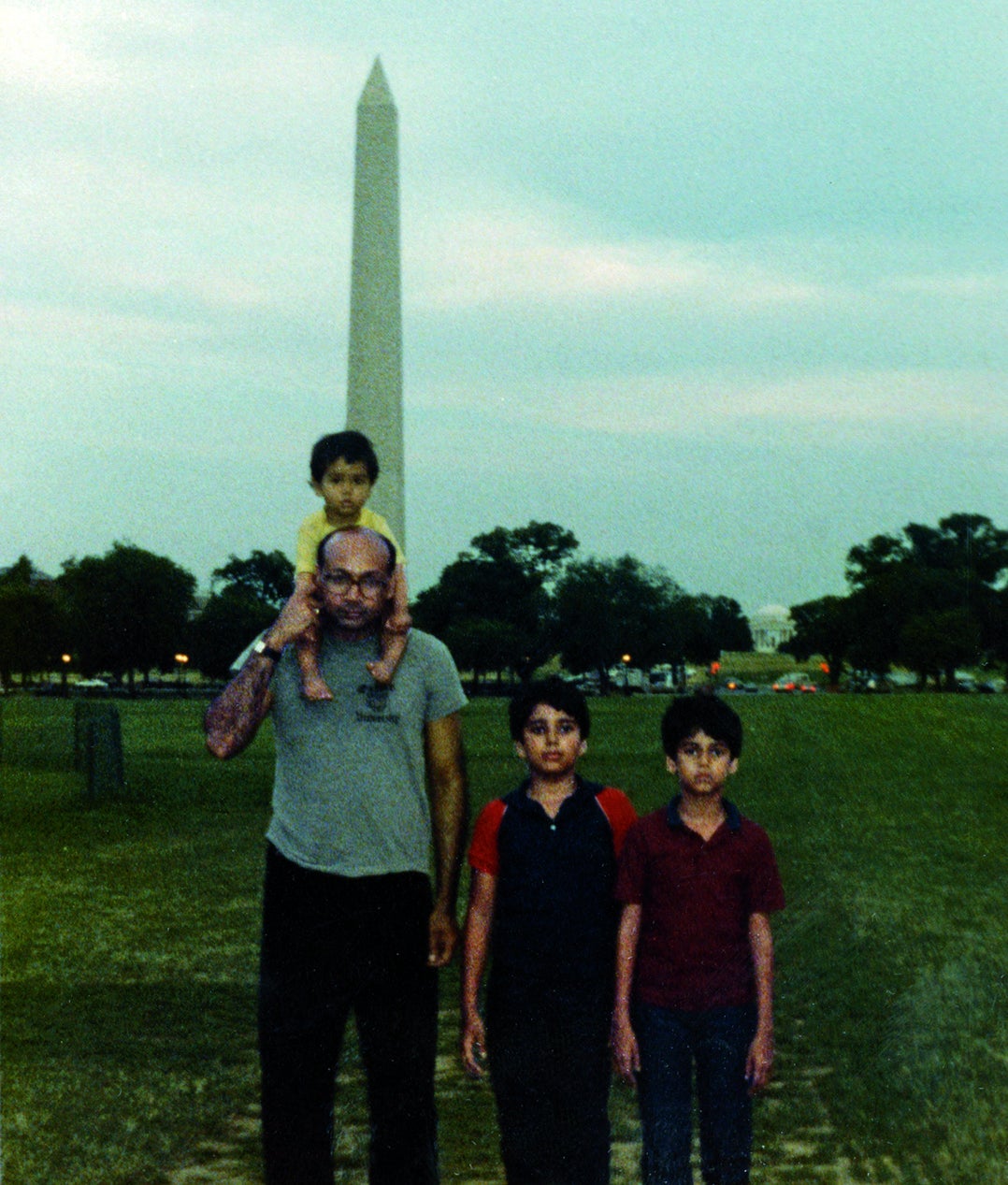

Khan’s writing weaves together moments that range from the hopeless — digging stale bread out of a garbage can while in university because he was literally starving — to the miraculous: being permitted to marry Ghazala despite an initially disapproving mother-in-law, finding a job as a lawyer in Dubai, getting into Harvard Law School, the blind kindness of total strangers. It’s noticeable, within that scope, that a significant percentage of the book is dedicated to the many things, big and small, that white people did for Khan when he made it to the States.

When you read An American Family, it’s easy to feel like Khan’s immigrant story is your immigrant story, but only if your immigration story is successful — meaning, only if you and your family made a comfortable home and experienced little to no racism, which Khan frequently says was true of their experiences as immigrants. (“Believe me,” he told me, “sometimes people insist on it, [that] it must have happened. But it really didn’t.”)

His American boss in Dubai helps Khan get a job in Houston so he can save up money to go to Harvard. Countless people make sure his wife and children are taken care of back in Pakistan as he toiled on the other side of the planet. Strangers — white, brown, Sikh, Muslim — give Khan a place to stay, a plate of food, a ride, whatever he needs to keep going. When Ghazala and the children come to the US permanently, a stranger from down the hall brings them bags of groceries.

The kindnesses Khan describes in the book seem to be, according to him, deeply American. Only here could such a family thrive. “Division is not [in] the American DNA, it’s not a part of the American fabric,” he said.

When you read the book — and when you talk to Khan — it’s tough not to think, Maybe you just got lucky.

Khan’s experience is precisely the kind of pro-America narrative trotted out — often by politicians — when we talk about the American dream, that anyone from anywhere can become anything. But it’s also rare, and his dogged belief in the purity of American rights and freedoms is hard to reconcile when thinking about a president who has tried to implement what some have called a Muslim ban and prevent trans people from serving in the military, or the many black people who are killed by police each year, or the thousands of immigrants who do deal with racism in the country. When you read the book — and when you talk to Khan — it’s tough not to think, Maybe you just got lucky.

If you’re young — namely a first-generation person of color like myself, whose family emigrated decades ago — listening to Khan’s relentless optimism can be frustrating. He sounds so much like my parents, immigrants themselves, maybe because that generation has a higher tolerance for the complicated legacies of their adopted countries. That their families are safe and settled is all-important to them in a way it may never feel to their children, who have different expectations of their country.

Khan asked me where my parents emigrated to, and reminded me of the same things my family always says. “They left everything they were familiar with ... and came to a strange place with one and only one sentiment, decision, and purpose,” he said. "That was to make life better.”

Even so, Khan seems to appreciate the more vocal irritation of the next generation toward any kind of injustice. “It’s a human sentiment, it’s a natural reaction to all the nonsense that exists,” he told me. But Khan is big on civility: civility in discourse, in politics, in dissent. “Civility dictates equal dignity,” he said, one of a few times it felt like he was really talking about a certain political figure without naming names.

Khan’s rhetoric seems inherently old-fashioned, but not in the way of white conservatives who are afraid of things like trans people in the military (at the end of the summer, Khan spoke in support of Human Rights Campaign, the country’s largest LGBT civil rights organization) or believe that women shouldn’t control their own reproductive health. Instead, Khan talks with the optimism of someone who has demonstrably lived through worse. Immigrating is hard: It’s hard financially, it’s hard emotionally, and it’s hard on your sense of self. By any definition, Khan’s life has been hard, and so neither Trump nor the current stirrings of fascism in and out of the US scare him as much as it might terrify the rest of us with less lived experience.

Khan and his family live in Charlottesville, Virginia, where the tiki-torch bearing neo-Nazi protests happened in August. When I asked him about those demonstrations, he told me, “I was standing outside my car on the road, watching the parade go by with torches and Nazi flags. [I] never thought that Nazi flags will be carried on the streets of the United States, right before my eyes. I heard all the ugly chants with my own ears.”

But, as in almost any case in which I tried to get Khan to talk about the brutality of American life, he was more interested in the positive aftermath, making an explicit choice to see the best in people. (Obama has often done something very similar; after Trump won, he reminded the country, “Everybody is sad when their side loses an election, but the day after we have to remember that we’re actually all on one team.”)

“The world only knows Friday and Saturday,” Khan said. “But what happened on Wednesday, that is the true America, that is the message of America throughout the nation. On Wednesday, there was a march of the citizens of Charlottesville. They took the same route where these Neo-nazis had marched.” Khan said that now, plenty of homes in Charlottesville bear a banner that says, “No matter where you are from, you’re our neighbor.”

“This is not the perfect place,” he says. “But this is the best place.”

An American Family purports to be a memoir, but in reality, it’s more like an exploration of patriotism. Patriotism that has faced real, tangible threats — a kind of patriotism that wouldn’t find football players taking a knee during the national anthem to protest police brutality disrespectful to the country. And when it comes to this topic, Khan is less concerned about people kneeling than he is about the visceral response to it. “I would do what I have seen my son to do when the flag is displayed or the anthem is played: We stand up and we show our respect. Person standing next to me doesn’t agree with me, that person has the right to disagree,” he said. “This interpretation of my way or [the] highway, that is not democratic at all.”

Though the first half of Khan’s life in the US had the elements of many stories of the American Dream — friendly, welcoming neighbors, a growing family — the second half featured unspeakable trauma. His son was killed in combat, and the grief was both unimaginable, and later, extraordinarily public. But through it, Khan’s patriotism has never wavered. Now, since Humayun’s death, they have a dining room table covered with hundreds of cards and letters: thank-you notes, words of solidarity and support. “I find them both soothing and inspiring, each a reminder of the fundamental decency of people,” he writes in the book. “My heart swells.”

The root of Khan’s affection for the US is clear: To him, it was just the best option, and he wants people to remember how fortunate they are to be here. “This is not the perfect place,” he says. “But this is the best place.”

Speaking for yourself, and for others, is exhausting. But the sheer act of talking, according to Khan, is what might help stop fascism from growing. He talks about receiving a 26-page letter from a retired army nurse who served in World War II. She was asking him to keep speaking, saying that open discourse could have stopped WWII. “Hardly people spoke of the viciousness of those who became the cause of the second World War,” he told me. “I continue to speak as much as physically and humanly possible, to make sure that we are aware.”

Khan doesn’t take a fee for his speeches; he says he draws encouragement and energy from talking to younger people, and the hope that the next generation will change what he cannot. “They’ve never seen anything like this, but how hopeful they are,” he said. “[They] are the custodians of these values and custodians of the Constitution.” The next step, then, is transforming patriotism into action.

Khan is quiet when he’s defending the Constitution, or choking down some unfavorable words about Donald Trump, or laughing about a memory of his and Ghazala’s neighbor when they first moved to the US. He’s so quiet that it can be hard to hear him; his voice is deep and everything can sound like a soft rumble. But when he talks about his son — almost always referred to by his full title, Captain Humayun Khan — his voice gets even softer, filled with air instead of gravel. Captain Khan was killed in action when he was just 27. He was the second of their three sons.

In his book, Khan tells the story of how his son died in a chapter called “Baba.” It begins with Captain Khan telling his family he wanted to join the ROTC, and ends with his memorials. The whole chapter feels like a kick slowly making contact with your gut; the inevitability of it is excruciating. While Captain Khan was stationed in Iraq, a suspicious taxi approached his checkpoint quickly. Instead of shooting at the unknown driver, he sent everyone else away and approached the car, which detonated before it was able to get to where hundreds of soldiers were sitting in the mess hall. Two people in the car and two bystanders were killed as well. Captain Khan was awarded a Bronze Star and a Purple Heart for stopping the suicide attack from killing even more people than it did. “He stayed true to the shape of his heart,” Khan writes. “Pride can be a balm, but it is not immediately effective, and it never, ever heals the wound.”

Among the honors bestowed upon Captain Khan after his death was a regiment named after him, Khan Regiment, in Fort Knox. “These 300 second lieutenants were in front of us and, at the end of the ceremony, I looked at Ghazala and said, ‘Did you see something?’ She said yes. I told her that I felt the exact same. Each and every one of them looked like Humayun to us. Literally. Literally.”

The Army became a kind of community for Khan and his wife after the death of their son. They’ve launched a scholarship in their son’s name, and they continue to invite a graduating class of cadets over for dinner, 15 or 20 of them every year since 2005, right after Captain Khan’s death. “When they entered our home — only parents would know this — we felt he has arrived. He has come.” It’s at these dinners that Khan came up with the idea of giving the graduates pocket Constitutions. For years, he gave them each copies of John McCain’s Why Courage Matters: The Way To A Braver Life, but “it got really expensive for me.” While renewing his bar license, he saw an ad for 99-cent US Constitutions, and ordered them for each of the graduates.

When talking about his son, Khan always comes back to the idea of division versus unity, and how division has to be temporary. He still has faith in people to do the right thing and to come together instead of being separated by their differences. He talks about letters he gets from deployed service members in Iraq and Afghanistan, people who years before, had dinner in his home, thanking them for the experience. (It is, more often than not, the first time some of these people have ever been in a Muslim house.) “That is where mankind is headed,” Khan said. “Not the divisions. Unity. Finding similarities with one another.”

When he does manage to come around to the topic of Trump, Khan talks about him like he’s a minor nuisance. “In the scheme of things, in historical process and all that, so what if [Trump] is reelected?” he said. “These results come and our rule of law will handle it, and so what? Now the country is very much aware of how bad it can be. The division has always been [there], of course, but we have overcome.”

What’s left to fear once you’ve lost your child in service to a country that you always wanted to be a part of?

And so maybe the reason for Khan’s calmness, while the rest of us seem panicked about the state of the world, is that he’s already paid the biggest price. What’s left to fear once you’ve lost your child in service to a country that you always wanted to be a part of? “Only parents know this,” he said before taking a long pause and running his hand along the table in front of him. “Losing a child makes a hole in your heart, which never fills. But you get used to it.” He swallowed hard and clenched his jaw, pressing his lips together as if to hold back a sob. “You try to make the best of it, you try to make some good out of grief, good out of tragedy. That is our effort and that has been a part of our life.”

In the introduction of An American Family, Khan relays a story about his grandfather, wherein he would quote poetry, explaining parables to him as a boy. In one example, his grandfather sits on his bed and quotes Rumi: “So what if you are thirsty? Always be a river for everyone.”

It’s a value, clearly, that Khan and his family have taken to heart in the last year, in the run up to the DNC, in their grief for their son, and even before that, when they were trying to chart a path to the US. You don’t just do it for yourself. You fight even when you’re tired. You let everyone drink even when you're thirsty. “If you would’ve asked me in June or July or August of last year, we had no plan, no capacity, no capability, no desire of being so public. It was just meant to be,” he said. “It was for the sake of others. That was the tradition. Captain Humayun Khan died doing that.” ●