In 1987, Playboy commissioned John Waters to interview his idol, Little Richard. “He had just put out an autobiography where he talked about being a drag queen, he mailed people bowel movements — he was right up my alley!” Waters told me. But the conversation was a bit of a bust. Little Richard wasn’t the campy, sprightly figure Waters was hoping he would be. “It didn’t end well. He didn’t have the mustache, he wore conservative suits, said anti-gay stuff,” Waters said. “I still love Little Richard, but there’s a thing where people say never meet your idols. That, maybe, is true.”

Waters couldn’t have known, but while on the Acela to Baltimore, where he has lived his entire life and where many of his movies are set, I was worried I’d have exactly that kind of moment with him. Most famous people don’t live up to our heady expectations, and if Waters was a little more tempered in person than his freak charmant public persona, no one could blame him. Still, I fretted. What if he was surly? Or what if he was boring?

I first heard of John Waters around 2003, when I was in junior high. Cable channels played Cry-Baby on a steady loop at 2 a.m. I had no idea what was going on in that movie — why was Johnny Depp collecting his tears in a jar?? — but it stirred something deep in my soul. That’s the whole thing about a Waters production; if you feel like no one sees you, or if you feel like you stick out too much, his movies are a salve. Freaks like us get to be the good guys, finally.

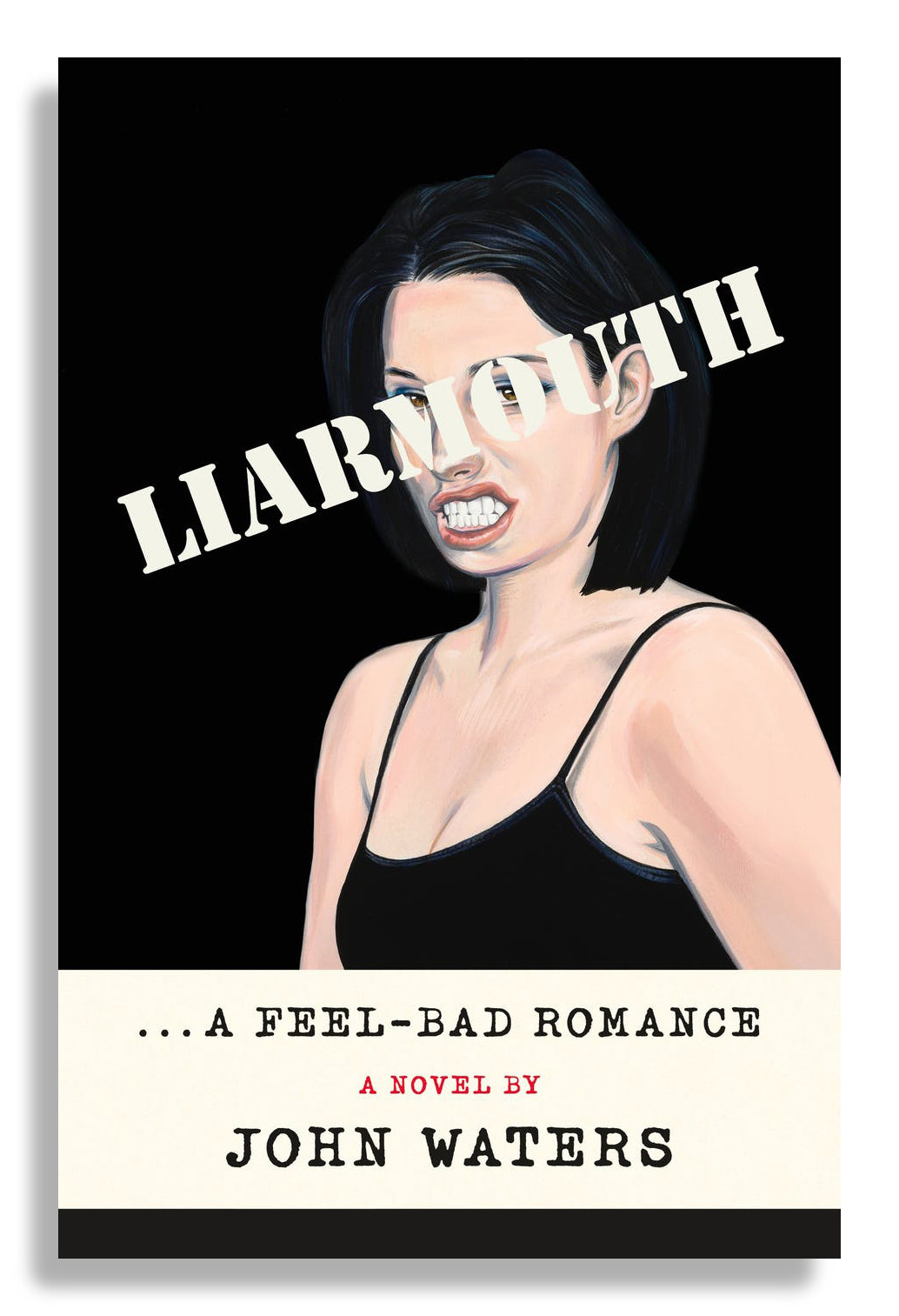

So here’s some good news: John Waters is exactly who you want him to be. Having just turned 76, he’s still riotously funny and quick — and also truly disgusting. For 50 years, Waters has been our self-appointed “filth elder,” guiding us into the perverse with cult classic movies like 1972’s Pink Flamingos, 1981’s Polyester, 1988’s Hairspray, and 1990’s Cry-Baby. As a director, he’s always had an eye for pleasing sleaze, like drag queen Divine eating a handful of dog shit with glee. (For years, my friends and I scoured the early internet hoping to find a clip of it, hoping it was real and not some urban legend, and we were utterly delighted when we found out: It was real, and it was spectacular.) As a writer — he wrote about hitchhiking across the country in 2014’s Carsick and about how to become and be famous in his 2019 memoir, Mr. Know-It-All — he knows exactly how to make you laugh while gagging. His latest offering is a debut work of fiction that again thrills in the most wretched way: Liarmouth is a novel about a liar who can’t stop lying.

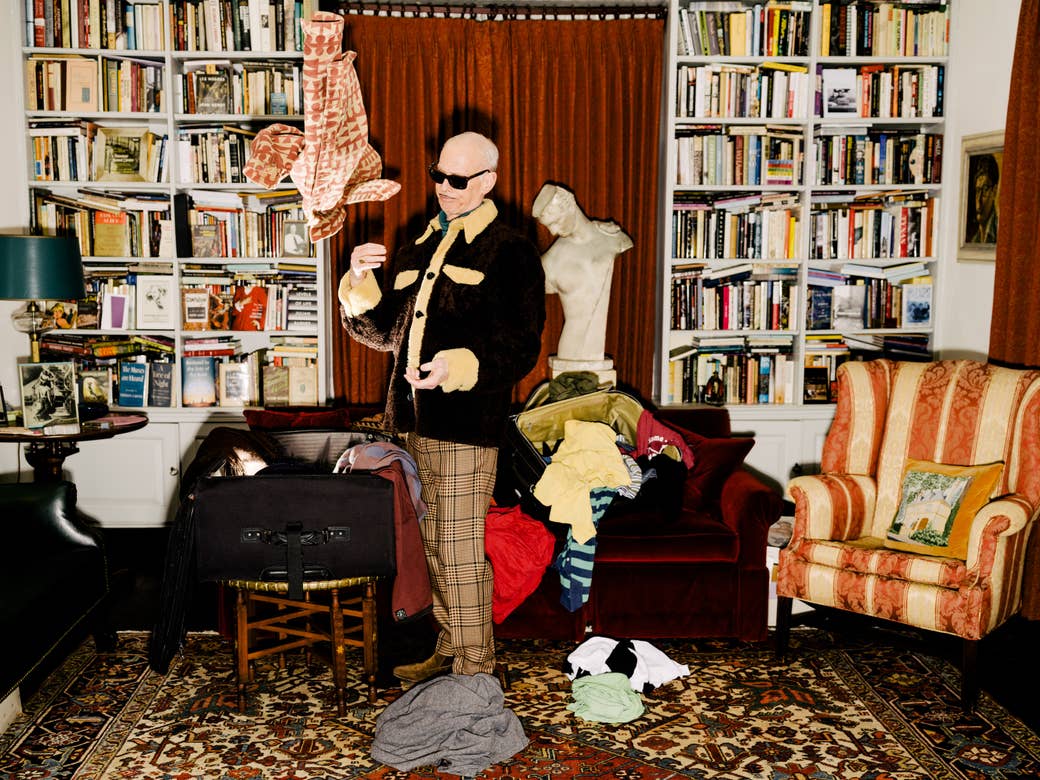

Waters’ house is nondescript, but he does have a small sign taped to a desk in front of his door, “authorizing” any deliveries to be left outside. His signature adorns the bottom as if it were a legal document and not the equivalent of a Post-it. When he opened the door, he waved me into his opulent salon, which was awash in red brocade curtains, tchotchkes, precious ephemera, and several tables covered with giant coffee table books.

He took a seat in an armchair and immediately started grinning.

John Waters has two smiles. One is a polite “thanks for coming to my home” smile, which I saw when he ushered me in. The other is a little Cheshire cat grin that spreads across his face, slowly, like an ooze, usually when he is about to say something perversely funny. Over the course of the two hours I spent in his home, it was thrilling to see him erupt in that smile over and over again.

There are 9,000 books in Waters’ home — in this one, at least; he has more in his New York apartment and Provincetown house. He also has a film archive elsewhere, where many of his prized movie possessions are kept. He claims all of his books are cataloged online so he knows which ones he owns. Does that mean he can find a particular book if he’s looking for one in his house? “Ehh,” he said, guiding me up a twisting staircase, past some decals of kittens on the wall, to his bedroom, which is almost preternaturally tidy and unremarkable, its queen-size bed tucked tightly with crisp white hospital corners. Conversely, one of his bathrooms appears to just be a storage room for colorful blazers and nothing else. Another crawl space was just for windbreakers. Waters has so many desks I lost count, but I only saw one television, which appeared to be 40 years old.

As he continued his tour, I glimpsed a sliver of a recognizable face on a canvas. “Oh, a Michael Jackson portrait,” I said.

“Yes!” Waters said, closing a closet so I could get a full view. “Michael Jackson looking through a glory hole!”

Then he motioned to a little wooden structure propped up on a side table — a birdhouse. “It’s the Unabomber’s house,” he said.

If you feel like no one sees you, or if you feel like you stick out too much, his movies are a salve. Freaks like us get to be the good guys, finally.

Indeed, the birdhouse was a replica of Ted Kaczynski’s cabin, windowless and all — just shrunken down. Next to it sat a horrible doll that looked like it had been electrocuted, waterboarded, and then set on fire. “Bill,” he said. “My fake baby.”

Waters has a lot of Kaczynski-themed art. He showed me an eerie framed photograph of the former location of Kaczynski’s cabin, with only the FBI fencing intact after the cabin was taken away as evidence. Waters’ attic also contains a hidden room that’s a recreation of the interior of Kaczynski’s cabin, to scale and replete in stunning detail. “Every single thing you need to make a bomb is in here except gunpowder,” Waters told me while I gawked at the piles of documents and dust that’s collected over the years. “That’s his wife’s pubic hair there.”

When I asked him why he had so much work dedicated to the Unabomber, he reacted as if I asked him what the point of music was. “It’s an art piece!” he said before wandering off.

We went downstairs and passed a life-size portrait of a man urinating on himself. “That’s Tony Tasset,” he said when I stopped to stare. “It’s called ‘I Peed in My Pants.’ Enron had it in their office or something.” Nearby, wedged between two doorways, sat a butler’s tray, covered with plates of fake nuts, raisins, and a peanut butter and jelly sandwich. Waters, a former smoker, still displays ashtrays, like an original piece by Yoshitomo Nara, now worth thousands of dollars. “Too young to die” is painted on the side.

The inside of Waters’ house is what I imagine the inside of Waters’ brain is like: strange and funny and totally surprising, every crack of it full of something else incongruous and unpredictable. His work has always been punk, a measure of rebellion and chaos. I asked Waters, as so many people have, whether the proliferation of online pornography has made it harder for him to shock his audience — after all, it’s a lot easier to find footage of a woman eating shit now than it was in the ’70s. “We didn’t do that for sex,” he said. “We did it for anarchy!” He said that Jackass was the movie most spiritually aligned with Pink Flamingos. “[Jackass] was a huge hit because it’s funny. No one jerks off and laughs.”

I haven’t stopped thinking about that line ever since — can you turn someone on while you tell them a joke?

Even if you haven’t seen a John Waters film, you’ve likely seen at least one John Waters quote, usually gussied up in pastel letters on Bookstagram: “If you go home with somebody and they don’t have books, don’t fuck ‘em.”

Now, Waters has an addendum: “If they’re cute enough, you ignore it.”

Actually, one more: “The other thing is, if they have books in the bathroom, don’t fuck ’em,” he said, giving an elaborate example of someone sitting on the toilet, grunting and straining while reading joke books on the john.

Speaking of assholes, there’s a ton of them in Liarmouth. The novel is a kind of “celebration” of rimming, Waters told me, and it ends at an analingus festival, which is stupid and timely. “In a way, I am hopefully embracing and making fun of political correctness in this book. Is there such a thing as analingus rights, and are they being discriminated against? Is it woke to be an analingus? I’m trying to come up with new minorities!” he said. (If you don’t know what analingus is, I implore you to google it.) “No one makes fun of themselves. I make fun of everything I love, and I make fun of myself first.” Liarmouth makes fun of everyone, but especially anyone who’s ever had a sexual urge in their life: tickle fetishists, cum rag rimmers, you name it. “All that moaning and thrusting and humping with another human. Swearing. Drooling. For what?” Waters writes in Liarmouth.

“I love radical sexual theories, even if I don’t agree with them,” he told me.

“Even grown men who dress up like babies and wear diapers?” I asked him.

“Adult babies?” he said, his Cheshire smile spreading. “Lock those fuckers up.”

Liarmouth follows the same traditions of most John Waters productions: It’s gross, unerotically sexual, shocking, offensive, and rowdy. The novel follows Marsha Sprinkle, a dog-hating, sex-negative, pathological liar who steals wallets and identities and hope. Her entire life is about deception — and she does it with gusto. She snaps at little kids. She sneers at men and their disgusting penises that want so desperately to slither inside of her because she is still beautiful and svelte. Really, she hates just about everyone, from people in the military (“post-traumatic stress time bombs”) to families with children (“nutcase Catholics”) to airline customers with disabilities (“fakers”).

Pooping is also too obscene for her to participate in; Marsha eats nothing but crackers to ensure that her bowel movements are delicate little pellets. She has a daughter, having been impregnated by a man while still a virgin via a series of butthole-related mishaps that I won’t ruin for you here. “She did have a reason to be traumatized,” Waters said. “She was with child from a cum rag rimmer!” (Marsha indeed gets pregnant not through intercourse but through a rimming mishap with her ex-husband, and you’ll really just have to read the book to get the full picture.)

The sex in Waters’ projects works because it’s depraved, and it speaks to that monkey element in our brains that wants to throw shit and piss and see where it lands. Of course it’s tasteless, but it’s also hilarious, the most important hallmark of any Waters project. It’s why he’s been able to get away with the shock of, say, a woman having sex with a chicken in Pink Flamingos. And the humor works because Waters never punches down. For most of his career, he was the one on the bottom, aiming upward at conservatives, anti-gay creeps, racist losers, and anyone who can’t take a fucking joke.

Punching up is how he’s gotten away with so much. “Empathy is important,” he said. “Especially if you’re the child of a cum rag rimmer. There’s not a lot of support groups if that’s your complaint.”

Some of Marsha’s characteristics are inspired by an old friend of Waters’ who also loved to ritualistically lie. “Lying made her happy. It’s why she got up every day,” he said. “She told people the wrong directions.” Before the pandemic, she would tell people there was a terrible pandemic going around. “People believe anything! She would tell people in line at the airport terrible things, [like] The flight’s been canceled,” he said. “She said she even felt prettier after she lied.”

The novel is another example of Waters turning an utterly distasteful woman into a kind of folk hero. He has always been able to take repellent, rude, crude, slimy women and make them iconic. Marsha is probably the worst person I’ve ever read in modern literature and yet I still rooted for her. I wanted her lies to work. She sits within a canon of Waters’ deplorable women, like Divine in Pink Flamingos or even Hatchet-Face in Cry-Baby, both off-kilter, emotionally ugly, and a little mean, but mostly just misunderstood.

“Villainous women are good parts, that’s all. I can write them well,” he told me, though he doesn’t necessarily agree with this categorization. “I didn’t think Divine was the villain in Pink Flamingos. Divine was just living her life in nature, doing her memoirs when she was attacked by a jealous pervert!”

There is a kind of order in Waters’ world, even if it seems fucked up. “The rules in my movies are the people that are judgmental and don’t know the whole story are villains, and the people that are proud of their morals — even if they’re completely wrong and insane — are the heroes as long as they don’t try to hurt anybody else first,” he said. “They use what society says against them as a style. They use it as a personality — not a disorder.”

The point of Waters’ career, ultimately, has been to make fun of whatever social norms constrain us. In the 1970s, for example, hippie culture was all the rage, so he made Multiple Maniacs, a film that was pro-violence. 1988’s Hairspray mocked the tedium of racists afraid of losing their place in the world. 1990’s Cry-Baby was about class warfare and white trash teens telling squares to get lost. If you watch a John Waters movie and intrinsically get it, it means you’re a part of a community of like-minded weirdos. People who belong nowhere can find themselves among their people in a John Waters movie.

People who belong nowhere can find themselves among their people in a John Waters movie.

“Everything I’ve done has made fun of censorship. I made fun of underground art movies. I made fun of political correctness today, of gay rules,” he said. “In my spoken-word shows, I talk about how we should scare straight people again. I’m tired of being accepted.” He suggests that the way to make straights scared again is for gay men and lesbians to start having sex with each other. “I always say: Men, consider the oyster; ladies, talk into the mic.” It is a very Waters way to view transgression; he is always lamenting the death of hookup culture. “If you want to be a radical, say you love sex. No one dares say that anymore.” (He asked me if “young people” were still having sex parties in Brooklyn, which I couldn’t really answer, because I am a loser. We both seemed kind of crestfallen about it.) In Waters’ world, dysfunction is beautiful, degradation is powerful, and there’s nothing to fear because the grotesque is proudly on display.

And while Waters’ work has always focused on the fringes, he’s become something of a mainstream cultural touchstone. He’s been in everything from Saturday Night Live to Search Party (selling a baby to a gay couple, very similar to the happenings in Pink Flamingos). But he doesn’t think of himself that way; he continually tries to push the envelope. “You can’t really say the material of the book is mainstream. I think it’s more nuts than something I’ve done in a long time,” he said. But he can admit that the kind of comedy he once had to fight to bring to the surface is now everywhere.

“The culture of filth, whatever that is, is American humor today. That’s why suddenly Pink Flamingos gets accepted to the National Film Registry. It’s great!” In the past, Waters has appeared on plenty of banned books lists, and his movies were routinely censored; Pink Flamingos was originally banned in parts of Canada and Australia, though it will soon be available via the prestigious Criterion Collection.

But there are still plenty of things that horrify John Waters: “stupidity, racism, Oscar-bait movies — even though I’m a proud Academy member,” he said. “So much, but nothing fun!”

What he hates the most, though, is judgment — people who cast it on others in ways that are punitive and cruel. Oh, and one other thing. “People’s outfits on airplanes shock me,” he said, pressing his fingers into his forehead. “Cutoff pajama bottoms? A filthy, dirty T-shirt? Flip-flops?” He groaned softly and tilted his head down, pressing the pads of his fingers into his creased forehead, whispering an indictment as that smile starts to spread again. “Appalling.”

Airport attire aside, Waters is not one to cast the first stone. “I try to get people out of jail who committed murder. Who am I to judge someone for touching a woman’s ass while running for election?” he said with a flourish of his hand when I asked about, ugh, cancel culture. “Look, I hated Bill Cosby before rape. And Harvey [Weinstein], am I sorry he’s in jail? No. He always said no to my movies anyway.”

Waters has an extensive oeuvre, and, look, not all of it is pretty — again, this is a filmmaker who is friends with freaks and miscreants, and who once went on Saturday Night Live to act as the model for creepy dudes everywhere. But if any of Waters’ work has aged poorly, he doesn’t care, and, really, why should he? He expresses few regrets for his past work — and a lot of it has aged well. But he does rue some of his gags. “When I made Multiple Maniacs, they hadn’t caught the Manson family,” he told me. The original ending to the 1970 film about traveling ransackers was going to say that Divine was personally responsible for Sharon Tate’s murder. “What was I thinking? But halfway through shooting, they caught them. They were the filthiest people alive. They inspired Pink Flamingos, and I’ve apologized for all the smartass things I said.”

Waters has dedicated a few of his films to Manson family members, and the murders were an ongoing theme in a lot of his work. There was also a “free Tex Watson” gag in Pink Flamingos (Watson is currently in prison for his role in the Manson murders) — which was, obviously, a joke, since he was never getting out, but maybe not a repeatable gag for Waters anymore.

The regret he feels stems directly from the decadeslong friendship he has had with Leslie Van Houten, one of the women convicted of the LaBianca murders. Waters became acquainted with her when Rolling Stone asked him to interview Charles Manson; Waters declined but began corresponding with Van Houten instead. “It changed my smart-ass stuff about serial killers, which she was not,” he told me. “I got to know her really well.”

Waters has a real redemptive bent. He believes people can improve and, in fact, wants to give them the room to do so. Over the years of his friendship with Van Houten, Waters has met her a few times in prison. “To me, she’s the perfect example of being rehabilitated by the California legal system. She helps women, she teaches people, she hasn’t wasted her life,” he said. “All you can ever do if you do something that terrible is to make yourself a better person.” (Van Houten is still incarcerated in California, though a parole board has recommended her release five times. Two governors have blocked the requests.)

Such is the power of words uttered beneath that pencil mustache.

Ever since he met Van Houten, he’s been advocating for her release. He has a slew of photos of her pinned behind his desk (the one specifically for “business”), next to one of Waters with Henry Kissinger, one of him with a very young Leonardo DiCaprio and Mark Wahlberg, and a scribbled note from Martin Scorsese congratulating him on the release of 1999’s Pecker. “She was 19 when she met the biggest mad man in history,” he said. “She looks back on it in horror — who wouldn’t? It was 1969, probably the most insane year ever since I’ve been alive.”

Waters was a child of the ’40s who grew up in the ’50s and came of age in the radical and tumultuous ’60s. In his lifetime, plenty of progress has been made (abortion rights, LGBTQ rights, increased racial equity), and progress has also atrophied (abortion restrictions, LGBTQ panic, painfully consistent racism). It’s tougher than ever to be transgressive; these days, that often means just being an asshole.

Like most people, I wanted Waters to tell me our current moment of historical unrest and agony wasn’t the worst it had ever been. I wanted him to tell me it would get better again — that we could make America filthy again. “Depraved used to mean fun,” he said when I asked how he felt about our current political depravity. “When I was young, the sexual revolution was having sex with someone different every night. But in COVID? You go to sex parties? What are they, bug chasers? Bossy bottom boosters?” It was strange, but in that moment I would’ve been delighted to be a bossy bottom booster myself, whatever that is — such is the power of words uttered beneath that pencil mustache.

In person, Waters seems to have no limits on what’s appropriate to discuss. And yet even the freakiest among us have boundaries. When I asked Waters what he did for his recent birthday, it was the only time I saw him stutter. “I had a birthday dinner with…someone I’m…well, with the person I’m in love with,” he said. I asked him who, but he demurred. “Oh, I don’t talk about it,” he said. “As soon as you talk about love in public, it disappears.” He wiggled his hands in the air as if to show affection disappearing in the ether. “I always tell Ricki Lake, ‘Don’t be talking about stuff that way.’ I totally believe that.”

This is maybe the only glimpse of vulnerability that Waters betrays while we’re together.

Near the end of our conversation, he picked up a Polaroid camera from one of the coffee tables in his salon. He didn’t so much ask to take my photo as tell me that it was going to happen. “I have everyone that’s ever been in here,” he said as I smiled for the shot. He leaned in and raised his eyebrows as if he was about to tell me where a body was buried.

“And everyone has been here.”

I was tickled. Doesn’t everyone want to end up in some kind of John Waters archive? Who knows what weird shit he does with those photos; they’re all hidden away. “No one’s allowed to open them until 10 years after I die,” he said. “I have cases and cases of photographs. You’d think it would be fun to look at them, but it isn’t, because people are dead.”

Frankly, it’s hard to believe John Waters himself is ever actually going to die. He doesn’t believe it either. “I’m not gonna die. I’m just going to get that one bit of moisture in the earth when I’m buried and I’m going to suck it and claw my way up through the worms and burst out for the resurrection,” he said, slashing the air with his hand while cackling.

Regardless, his legacy has outpaced him anyway, and it’s clear that no one person will be able to take over as our filth elder in his absence. “The future of filth is up to young people,” he said. “The ones that have the duty are the ones that get on your nerves, the ones who, when they do something, you say, ‘But alright, that’s going too far.’ But you laugh.”

Even if the world is in its darkest place, Waters thinks, there’s still room for a good joke. “If the world is sad and sick, they more than ever want to laugh,” he said. “I’m an optimist. If this is the end of the world, at least we didn’t miss anything.”

As our interview was winding down, he offered to drive me into town, essentially a small intersection with a bookstore (where he picks up his fan mail, which, yes, he reads) and a few new restaurants. He drives a nondescript Buick. “I like people who are rich in Switzerland. They hide it,” he said. “Or I like how Brad Pitt’s famous. He just drives a shitty old car.”

I always wonder what celebrated weirdos would’ve done with themselves if they hadn’t found their niche. Can you imagine John Waters working in accounting? Or trying to help you buy a couch at West Elm? “I’d be a good defense lawyer, a good psychiatrist,” he said. “But I don’t know all the answers.”

He paused for a moment — though not a long one, because he talks so fast that your ears can hardly keep up. “No. The answer is that after you reach a certain age, you just have to take responsibility for your life,” he said. “You can blame it on other people all you want, but too bad. We’ve all been dealt a hand.”

All day I was anticipating a prosaic moment, a flash of Waters being flawed or tedious or unimpressive or unfunny or dull. No such thing. Even when he speaks plainly, it still connects with the little creep inside of you, 13 years old, eyes glued to Divine’s hip padding in Hairspray, your inner monologue wondering, Why does watching this make me feel happy?

Waters rescued generations of freaks from their loneliness. We’ve been lucky to have him. “Life ain’t fair. I’m lucky. I got a good hand,” he said as he turned to me and smiled one more time. “How was your hand?” ●