In mid-February, Dr. Phil aired an episode about a 56-year-old woman named JoLynn with an alcohol addiction. But unlike other shows — or even an old Oprah episode — she isn’t coiffed or remotely prepared for the interview. She’s very clearly intoxicated, disheveled, and isn’t wearing any shoes. She rambles and at one point, starts to walk away from her chair. When Phil McGraw (more commonly known as Dr. Phil) asks her repeatedly where she’s going, she looks like a lost child. “I don’t know,” she says, over and over again. It’s not entirely clear why she came to McGraw of all people for help, and the show seems far more inclined to zero in on her confusion and intoxication.

Dr. Phil premiered nearly 20 years ago as an Oprah Winfrey–endorsed platform for McGraw. McGraw holds a doctorate in psychology, but stopped renewing his license in 2006, and has never held a valid psychology license in California, where the show is filmed. (A spokesperson for Dr. Phil confirmed that he ceased renewing his license in 2006 “as he no longer worked as a therapist.”)

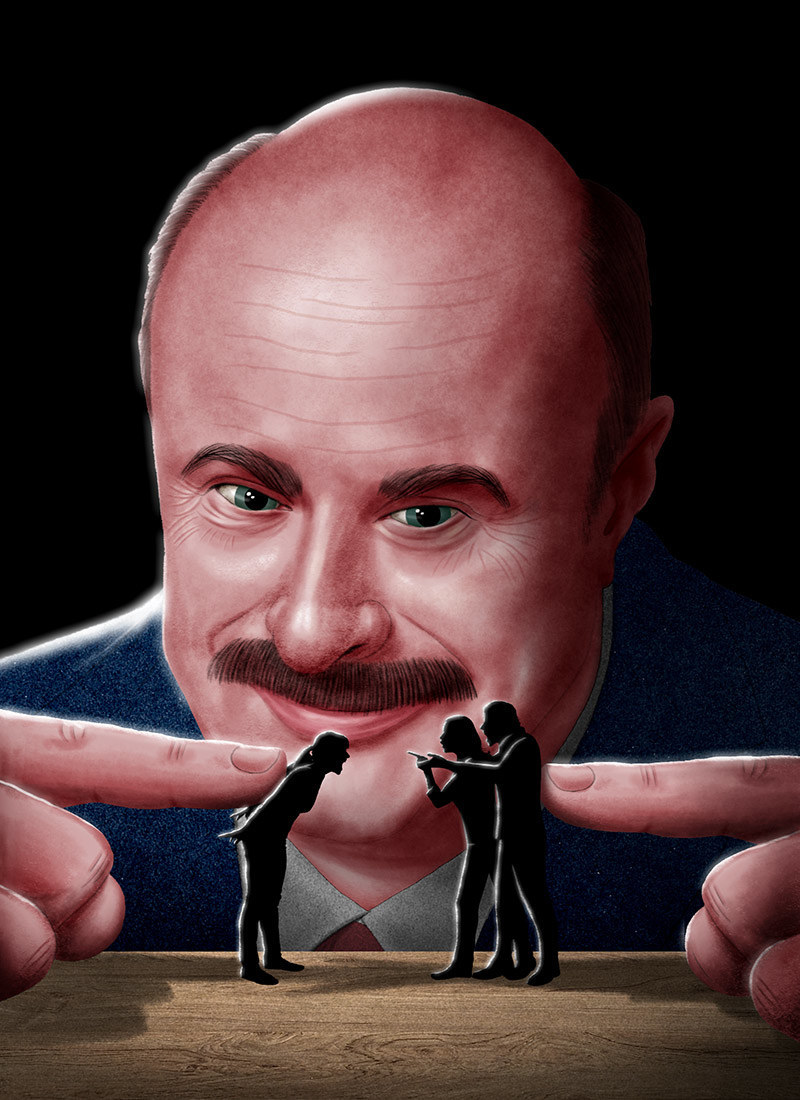

Early episodes featured couples in troubled marriages, people trying to lose weight, and other topics relevant to the show’s target demographic of people available to watch an hour of television at 3 in the afternoon. McGraw would sit with his guests and offer “psychological” advice, masked in the approachable language of a life coach or high school guidance counselor. He’s not actually anyone’s doctor, but he speaks with the authority of someone who thinks he is.

If you have more information or a tip regarding your experience on Dr. Phil, contact scaachi.koul@buzzfeed.com, or reach us securely at tips.buzzfeednews.com.

I started watching Dr. Phil in junior high, an after-school activity my mother made me do with her as some botched attempt to get us to talk about “serious topics.” She made me watch the teen episodes in particular — ones where young girls were seduced by nameless gangs (this was not a risk for me) or hard drugs (weed, it was only ever just weed). After an awkward hour of watching McGraw berate the parents, my mother would turn to me and ask: “So what did you learn?” The real answer was “absolutely nothing,” but the one that got her off my back was “don’t go near a boy.”

In my adulthood, I started watching the show again just as a kind of familiar background noise, and discovered that it had morphed into something much more caustic and ugly. There are episodes exploiting people’s devastating alcohol addictions, older men and women getting catfished by a fake Nikki Sixx, and a constant parade of “bad teenagers” eventually set right after being referred to a horse-centric boarding school. The show’s sole purpose is now seemingly all about displaying people’s difficulties in their crudest forms, and less about actually trying to help them.

Dr. Oz, possibly the other worst thing Winfrey unleashed upon an unsuspecting public, gets most of the smoke when it comes to talking about the failure of television healthcare professionals. Don’t get me wrong, Oz deserves it: He hawks vitamins you don’t need, anti-science rhetoric about weight loss and hydroxychloroquine, and even argued that increased deaths due to schools opening mid-pandemic might be worth it. But while Dr. Oz has faced plenty of controversy, McGraw continues to thrive. In 2020, McGraw made $65.5 million, all on the backs of thousands of people who came to him and his producers, desperate for help. He’s signed on to host the show through to 2023, into Dr Phil’s 21st season.

Mental healthcare around the country is lacking. Affordable care is hard to access, and that’s if you have any coverage at all. Television therapy, then, is what people get instead, and McGraw doesn’t just give bad advice, but he openly mocks the people coming to him for help. What may have started as a show intended to make therapy and open communication more accessible to people at home has warped into a creepy, exploitative program. Worse, his focus on women and teenage girls who have been abused means the show is now designed to go after people who can rarely defend themselves against a television behemoth. Dr. Phil is just Jerry Springer in a better suit.

He’s also still incredibly successful — in July 2019, Dr. Phil hit 150 weeks as the top-rated syndicated daytime talk show, with an average daily audience of 2.9 million viewers. Even in reruns, he kills.

A reconsideration of McGraw’s work has sort of begun, but his critics tend to get more attention when the targets of his “advice” are well known. In 2016, when The Shining star Shelley Duvall — who has been vocal about her mental health struggles — was featured on Dr. Phil, other celebrities spoke out about how obviously exploitative it was. “There shd [sic] be laws to protect mentally ill people from tv talk show predators like @DrPhil who is exploiting Shelly Duvall for his own gain,” tweeted Mia Farrow. Stanley Kubrick’s daughter called it “lurid entertainment,” asking for others to boycott the show. (In a statement to the Hollywood Reporter in February, a spokesperson for Dr. Phil said, “We view every Dr. Phil episode, including Miss Duvall and her struggle with mental illness, as an opportunity to share relatable, useful information and perspective with our audiences … Unfortunately, [Duvall] declined our initial offer for inpatient treatment that would have included full physical and mental evaluations, giving her a chance to privately manage her challenges.”)

For some reason, the Dr. Phil show fancies itself a “teaching tool” instead of a modern-day carnival freakshow designed to make viewers feel better about themselves. McGraw isn’t a medical doctor. At best, he dispenses questionable advice to the people who come on his show, and at worst, for postshow care, he refers them to at least one treatment center that is currently facing multiple allegations of abuse. If only McGraw and the show’s producers would just be honest about the product they’re making, they could really dig in, go for broke, and make the unadulterated reality TV trash they’ve been inching toward for 19 seasons.

Oprah Winfrey first started working professionally with McGraw in 1995, when Texas cattle ranchers sued Winfrey for libel, and she hired McGraw’s legal consulting firm. (He cofounded a trial consulting firm that offered help with litigation psychology, trial consulting, and witness training.) Winfrey won her case, and was so pleased with McGraw that she started bringing him onto her show as a relationship and life expert, starting in 1998. He wore brown suits and offered aphorisms for routine issues that come up in one’s life: marriage, divorce, child-rearing, the basics. But back then, McGraw’s topics and advice felt almost wholesome. He was a little funny and, frankly, kind of mundane.

He talked about “How to Rid Yourself of Toxic Relationships,” or “5 Pieces of Advice for Dealing with Toxic People,” or “Lifestyle Makeovers: Toxic Relationships,” a real variation on a theme. “You gotta put some effort into this,” McGraw told a husband on Oprah who wasn’t romancing his wife sufficiently, “unless you like masturbating a lot.” With these kinds of quips, McGraw set himself apart as the no-nonsense, unpretentious, down-home advice-giver to average Americans everywhere. Dr. Phil has a PhD in clinical psychology with a focus on forensic psychology, but he wasn’t some woo-woo therapist who wanted you to get in touch with your inner child or a New York shrink who wanted to know about your relationship with your father. He joked about being bald and made references to how Hollywood has fucked with our understanding of romance — he was approachable and relatable.

By 2002, Winfrey was producing his stand-alone syndicated daily show, Dr. Phil, and by 2008, the only talk show beating him was by the queen herself: The Oprah Winfrey Show. And if you watch a Dr. Phil episode from the early aughts, it still feels pretty quaint. The show continued the format it started on Oprah with normal-ass advice for normal-ass people.

Dr. Phil is just Jerry Springer in a better suit.

But then the show’s tone began to change. In 2004, Erin and Marty, a married couple on the verge of divorce, brought their teenage daughters on Dr. Phil. Fifteen-year-old Alexandra was pregnant, while 13-year-old Katherine resented her sister for getting pregnant and taking up any attention she might have gotten from her parents. Their appearance on the show was the first real hint that McGraw may have been less interested in helping frazzled moms and dads communicate with their moody teenagers and more interested in exploiting the wild trauma that’s hidden in the suburbs.

Dr. Phil went back to this family for years — the last segment he did was called “Alexandra’s Progress…and Setbacks” in 2012, where Alexandra came on the show to talk about her past drug addiction and is then tasked to “write a mock obituary” to see what she has to say “about the life she would have left behind.” The segments revealed all kinds of personal details about the family, from Erin’s eventual face-lift to Alexandra going on birth control. The parents had their fair share of camera time, but the daughters seem to have been exploited the most, from the time they were teenagers to when they became adults. In the 2009 episode “Katherine in Court,” McGraw grills the youngest daughter after she’s arrested for lying to the police and covering up for her possibly abusive boyfriend. It’s unclear if she was ever convicted. (Katherine was 19 during this segment.)

But no one got it worse than Alexandra. She was never really able to shake off the stigma of being a teen mom on the show, and with every successive child and relationship, the show found ways to turn her life into fodder. 2010’s “Behind the Bruises” features McGraw speaking one-on-one to Alexandra’s fiancé, Tony. McGraw gets Tony to take a polygraph test to find out if he left bruises on Alexandra’s 2-year-old. It may be true that he may not have been a great fit for a father, but McGraw is exceedingly harsh and judgmental on both Alexandra and Tony, focusing mostly on brutal critiques rather than feasible advice. In 2011’s “Alexandra in Danger,” the producers follow Alexandra as she goes to her doctor to get her opioid prescription refilled, a prescription the show’s editing suggests she’s abusing.

The series concluded with “Alexandra’s Progress...and Setbacks,” where she joins her parents on the Dr. Phil stage to “candidly” discuss the details of her personal rock bottom and “comes clean about her darkest drug-fueled days...from carrying a gun to using dirty needles.” I reached out to Alexandra, Marty, and Erin for comment about their time on Dr. Phil. Neither Marty nor Erin replied to our request for comment. Alexandra would not comment for this story.

Now, most Dr. Phil episodes traffic in what I would call “Schadenfreude Television.” Episodes aren’t really about helping the people who come on the show so much as they are about scolding whoever is the most in the wrong. The trouble is that, as is true with mental health cases, the “bad guy” is often also the person who needs the most care and empathy. In a February episode from last year, 24-year-old Gabby appears on the show. Two couples, who she promised to bear children for, confront her. (They had never met before; the arrangement was entirely online.) Gabby was never indeed pregnant — in fact, she’s infertile and chronically ill, with a life expectancy of around 30 years. Gabby’s father explains that his daughter has psychosis, has bipolar disorder, struggles with structured learning, and has special needs. Her mother died a few years earlier, which was around the time that some of Gabby’s mental health issues began emerging. At the same time, she was constantly bullied at school. Gabby isn’t just some mean girl on the internet who wanted to fuck with strangers. That’s just too simple a story.

Her scam wasn’t illegal because Gabby never asked for money or items from the couples she lied to; it’s just tragic, hurtful behavior from someone deeply isolated and in dire need of mental healthcare for multiple past traumas. Most of the episode focuses on the producers following Gabby around backstage, begging her to come onstage when she clearly doesn’t want to. They call her “difficult” and “volatile,” and though she signed an appearance release, it’s not clear to the audience that she has read and understood it — when a producer asks her on camera to confirm she understands the waiver, she doesn’t respond and covers her face with the pages of the release. But she’s certainly remorseful, and seems to feel guilty; in a pretaped interview, Gabby cries to the producers, “I just want to say sorry to everyone that I’ve hurt.” When she walks off the stage in anguish, McGraw merely sips his water and sighs. The episode is near unwatchable.

As is true with mental health cases, the “bad guy” is often also the person who needs the most care and empathy.

But these kinds of scenes are what Dr. Phil became known for around 2010 — less about therapy, and more about finding those with extreme views and pitting them against one another in the worst kind of early-aughts reality show way. In fact, there are a few people who’ve worked on Dr. Phil who also used to work on The Jerry Springer Show, including one of McGraw’s longest-running segment producers, Deborah Whitcas, who worked there from 2005 to 2008. Springer was never about helping anyone or improving someone’s mental health, but just about finding the biggest freak and putting them onstage, ideally to fight with other freaks. Dr. Phil has replicated the format, but with a veneer of respectability that isn’t really earned.

A 2017 investigation by Stat and the Boston Globe discovered that the show’s producer allegedly supplied guests with alcohol and prescription medications before they went on air. “It’s a callous and inexcusable exploitation,” Dr. Jeff Sugar said to Stat, assistant professor of clinical psychiatry at the University of Southern California. “These people are barely hanging on. It’s like if one of them was drowning and approaching a lifeboat, and instead of throwing them an inflatable doughnut, you throw them an anchor.” (Martin Greenberg, a psychologist who works on the show as the director of professional affairs, denied the allegations when they first were made public. “We do not do that with this guest or any other,” he wrote in a statement, saying the allegations were “absolutely, unequivocally untrue.”)

As the decade progressed, McGraw started to rely on a different group of erratic, frustrating, and vulnerable people: teenage girls.

In 2016, then 13-year-old Danielle Bregoli was interviewed by McGraw on an episode called “I Want to Give Up My Car-Stealing, Knife-Wielding, Twerking 13-Year-Old Daughter Who Tried to Frame Me for a Crime.” You likely know Bregoli as Bhad Bhabie, who barked at the audience, “Cash me ousside, howbow dah?” when they laughed at her absurd blaccent and put-on tough-girl attitude. But Bregoli was barely a teenager, and her first appearance on Dr. Phil made her a cultural oddity, while the show got a viral attention injection.

Bregoli, like many of the teenagers on Dr. Phil, was referred to Turn-About Ranch, a “therapeutic boarding school” in Utah for troubled teenagers. It’s a real working ranch, as McGraw loves to remind his guests when he presents it as the last-ditch option for their kids. Periodically you get an update from the ranch — Bregoli herself gave an update from atop a horse, without the fake accent. “I just feel okay with who I am now,” she says in the segment. “I don’t have to put on a front to impress anyone.”

But in 2018, on her song “Bhad Bhabie Story (Outro),” she talks about the experience far less favorably. “It was pretty miserable. I did not know what was going in the real world — this place was far away from anything. There wasn’t even service there,” she says in the song. “A couple weeks after being home, I finally decided I wanted to meet up with my best friend again, somebody who was not good for me at all. Instantly, I’d say it was the next day … we got back to doing our old shit again. Smoking, trying to finesse people for money, just doing really, really dumb shit again.” When she rejoined social media after she got home from the school, she realized she was already a meme because of the Dr. Phil segment. Why wouldn’t she then lean into her worst behavior? She was already famous for it, her face and name published and memed and then republished and memed again.

It’s not clear if Turn-About is actually helpful to the kids who go, or if it’s just another facility that takes advantage of the minors who are sent there to get better. Just last week, 19-year-old Hannah Archuleta sued the school for an alleged sexual assault that she said happened to her when she was staying at Turn-About at just 17. (This is likely to be a high-profile case too, with Gloria Allred representing her.) Turn-About administrators provided a statement to me saying they “took immediate action” after Archuleta claimed she had been assaulted, but that her father removed her from the facility “before we could conduct a full inquiry.” The statement continued: “We would never take lightly an allegation of mistreatment to any of our students. Now that this incident is the subject of litigation, we must withhold our full response for a later date.”

Aspen Education Group was the owner of the ranch, which was then bought by CRC, which is now owned by Acadia Healthcare. In an email statement to BuzzFeed News, Acadia’s Director of Investor Relations Gretchen Hommrich said “It is my understanding that Turn-About Ranch and Aspen Education Group were closed or sold prior to Acadia’s acquisition of CRC Health. In any event, Acadia never operated either of the facilities.” Turn-About has gone through multiple owners and since 2014, has been owned by current and former employees of the ranch.

But Aspen Education has been accused of multiple infractions by former attendees, including lawsuits that claimed psychological torture, abuse, sexual assault, and human trafficking. The torture suit was dismissed, but CRC — the owner of Aspen Education at the time — declined to address specific allegations at the time. Arcadia did not answer our questions about these allegations either.

Bregoli was barely a teenager, and her first appearance on Dr. Phil made her a cultural oddity, while the show got a viral attention injection.

Some of these allegations predate Dr. Phil’s teen-centric episodes, and yet the show still referred its teenage guests to Turn-About Ranch. (Dr. Phil and the show have not been named in any of the litigation regarding the ranch.) “The Dr. Phil program is aware of the allegations and lawsuit against Turn-About Ranch and will continue following developments to determine any potential future course of action regarding that organization,” a Dr. Phil spokesperson said to BuzzFeed News. Since Archuleta’s allegations, Bregoli has spoken publicly about her own alleged abuse at the ranch, claiming that the administrators restricted food and wouldn’t let them change their clothes for days on end. “You’re helpless. You can’t call your parent. You can’t email your parent,” she said in an Instagram Live in late February. “If the state says they have to give you two pebbles, they’re going to find the smallest fucking pebbles to give you... That’s supposed to help kids get over trauma,” Bregoli said. “I would’ve rather went to jail.” (Through her representative, Bregoli declined to comment for this story.) In a statement to BuzzFeed News, a representative of Turn-About Ranch said, “We enjoyed our association with Danielle. While we strongly disagree with her account of the time she spent with us, we continue to wish her well.”

Bregoli got the most attention as a teenager on Dr. Phil, but she’s just the tip of the iceberg. Searching “Dr. Phil teenager” on YouTube gives you a wild array of results, from “Young, Privileged, and in a Deadly Gang” in 2014 to “Teen Explains Molesting Sister Twice” in 2017. And while teenagers of all ilks are featured on the show, McGraw seems to take the most aggressive approach with teenage girls. Their most vulnerable private moments — screaming and crying at home — are used on the show until the very end, when their parents decide to send them to Turn-About.

Their farewells always came right after an “After the Taping” segment, during which the girls break down over being sent to a facility in another state that they’ve never heard of, against their will, by their parents who they already don’t trust. And do they get better? Who knows; there are rarely any updates on any of these kids. They’re seen for an episode or two, and then forgotten, just another blip in Dr. Phil’s decadeslong oeuvre.

McGraw isn’t the first to traffic in messy human behavior; Phil Donahue, Jenny Jones, and even Oprah did it all the time in their heyday. But again: Dr. Phil espouses mental health advice. There’s a belief that you’re coming on the show to be mended in some way, not mocked and jeered at by a live studio audience. In 2004, McGraw did an interview with the family of a 9-year-0ld boy whose parents said he was being violent and abusive, namely to his younger sister. McGraw said the child had nine of the 14 characteristics of a serial killer. “Jeffrey Dahmer had seven,” McGraw said.

“Dr. Phil purports to be a mental health professional but he’s diagnosing from videotape, on the air,” said then–executive director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness Michael Fitzpatrick to the Washington Post in a 2004 story about Dr. Phil’s bad psychotherapy. “It’s unethical to do that sort of, if you will, pop psychology … You don’t do that for ratings. This is a human being.” A spokesperson for Dr. Phil at the time said that McGraw “never labeled” the child as mentally ill, which is technically true. He merely brought up Jeffrey Dahmer.

Reconsiderations always feel a little lousy. Sure, we all hate Justin Timberlake now but we could’ve saved a lot of time if, 20 years ago, we recognized that we don’t need to reward a young man for blathering on about his sex life with his ex-girlfriend. And it’s not like we aren’t presently doing the same to other, younger, newer celebrities. (One day, we’ll be watching documentaries similar to Framing Britney Spears about the discourse around Megan Thee Stallion’s shooting.) Eventually, McGraw will be viewed as the villain in a story like this, an adult man with power and money and the daily ability to potentially ruin a young person’s life.

But the damage is not relegated just to Dr. Phil. In 2008, McGraw created a spinoff called The Doctors, featuring a rotation of different medical doctors, namely a plastic surgeon, an obstetrician, and an ER physician who talk about different topics related to personal health. A 2014 study of The Doctors looked at episodes from early 2013 and determined that only 63% of their recommendations could be proven as credible.

Maybe it would be better if Dr. Phil were just called Phil, and if it lived as a Jerry Springer lite. At least then there wouldn’t be the pretense of offering real help to people who desperately need it. But he uses his PhD in psychology as a cover.

Good mental healthcare is hard to identify, but it rarely involves making your “patients” go viral, attempting some form of diagnosis of a guest’s behavior, or shaming women for sex work. (It also likely does not include putting your name on a line of ineffective weight-loss products or arguing that maybe quarantine is a bad idea because people die all the time from all sorts of things.) He benefits from his viewers not knowing any better.

Dr. Phil’s ratings are still incredible after all these years. The thirst for a daytime television doctor hasn’t slowed down, especially with more people home all day, in the middle of a public health crisis. But how sloppy does McGraw’s show need to be before his audience realizes he’s not a very good psychologist, but just a guy who spouts a few folksy sayings and then hides backstage? Almost everyone could use some good mental healthcare, especially now. But when it comes to McGraw, nothing would be better than anything he has to offer. ●