In 1981, Alice Sebold was 18 and a first-year college student in Syracuse, New York. One evening while walking through a park at night, she was violently raped and beaten by a young man around her age. “He pounded my skull into the brick,” she wrote later. “He cursed me. He turned me around and sat on my chest. I was babbling. I was begging.” Her assailant threatened to kill her. He choked her, raped her, and then robbed her. By 1982, Anthony Broadwater was convicted of the attack. He spent nearly two decades in prison for the crime. In 1999, Sebold published Lucky, a grisly and detailed memoir about her rape, the process of working with the police as a victim, and the PTSD she struggled with in the aftermath of the trial.

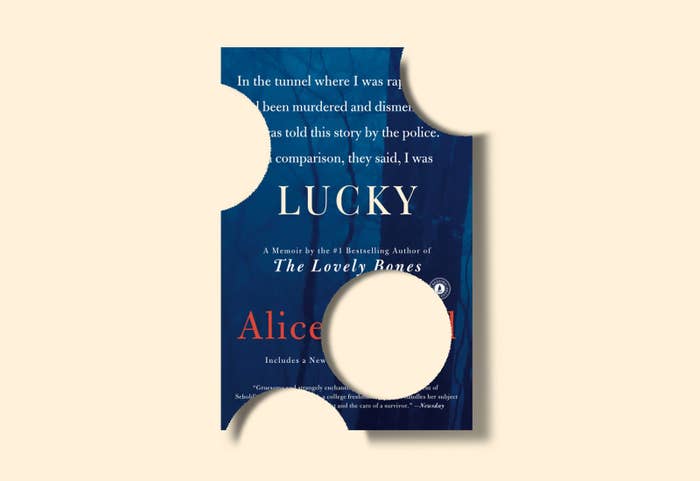

But Lucky — which Scribner, the book’s publisher, just pulled from shelves — now functions as an illuminating text about the failures of the criminal justice system. Broadwater was released from prison in 1998, but he has always maintained his innocence; in fact, he was denied parole five times during his 16-year sentence because he wouldn’t admit to committing any crimes against Sebold. But on Nov. 23, a state judge and the county’s district attorney exonerated Broadwater, now 61, agreeing that the case against him was deeply flawed. Sebold released a statement on Nov. 30: “I want to say that I am truly sorry to Anthony Broadwater and I deeply regret what you have been through,” she wrote. “I will continue to struggle with the role that I unwittingly played within a system that sent an innocent man to jail.” Sebold is white. Broadwater is Black.

Lucky — which Scribner, the book’s publisher, just pulled from shelves — now functions as an illuminating text about the failures of the criminal justice system.

Even worse, perhaps, is that the only reason Broadwater got his conviction overturned 23 years after serving his sentence was that Lucky was going to be adapted into a movie. It was set to star You’s Victoria Pedretti until Tim Mucciante, an executive producer on the film, started to question Broadwater’s guilt. After noticing significant differences between the book and the first draft of the script, he eventually hired a private investigator to look into the case. The movie has since been scrapped entirely, and the story of Broadwater’s wrongful conviction is now being turned into a documentary called Unlucky.

The FBI would later admit that the forensic analysis, which linked a sample of Broadwater’s hair to that which was found on Sebold, was unreliable data. Even Lucky gets at her own unreliability as a witness: During a police lineup, she identifies the wrong man because they looked “almost identical,” she writes in her memoir. She also writes that police officers seemingly egged her on, encouraging her to identify someone and to be a “good” victim, a helpful resource.

Lucky sold over a million copies and led to her best-known work, a novel called The Lovely Bones. At the time Lucky was published, it was an utter rarity for a woman to write a memoir (under her own name) about such a brutal, violent, dehumanizing attack. The first 10 pages recount her assault in minute-by-minute detail, and the entire book is a kind of testament to when the justice system works. But it didn’t. We know that for sure now. More than 20 years after Sebold’s memoir was first published, Lucky reads like an endorsement of a justice system well beyond reform.

Like most pieces of art, Lucky is a relic of its time. Plenty of details are unsavory even without the news of a wrongful conviction. Almost immediately after being raped, Sebold runs into her friend’s Black boyfriend, who offers to give her a hug. When she declines, he asks her if her assailant was Black. She says yes, and he apologizes. “He was crying,” she writes. “I cannot even now imagine what was going on inside his head. Perhaps he already knew that both relatives and strangers would say things to me like ‘I bet he was black,’ and so he wanted to give me something to counter this, some experience in the same twenty-four hours that would make me resist placing people in categories and aiming at them my full-on hate.”

Throughout the book, she seems frustrated that she has to contend with her attacker's race, but she also brings it up constantly. She thinks about her rape when she sees a “black man squatting on the sidewalk in West Philadelphia” or how she will soon have to “educate” her family that “it’s not all blacks” who commit assault. She writes about feeling an intense kind of fear “around certain black men ever since the rape.”

She’s so fixated on being good, and on helping the police get the bad guy, that she maybe couldn’t see her role in a system designed to punish innocent Black men like Anthony Broadwater.

Rereading Lucky is difficult because it’s a book from the ’90s about an event that happened in the ’80s. Sometimes, it really reads that way — it can feel dated by any current context. But Sebold seems aware of her privilege, and I can see her point that having someone like her write a book like this would be powerful, especially back when it was published: “I used the thing that I loved the most, which was language, to translate into prose the worst violence I had ever known,” she writes in the afterword. “But I was smart enough to know that just as inside any courtroom, the success of my presentation may have been based not only on the power of my words but also on my appearance and behavior.” She acknowledges that she’s white, middle-class, college-educated, and that, to some, she doesn’t seem like “the type” who would be assaulted. There’s power in giving words to gruesome experiences. And it is abundantly clear that Sebold was viciously assaulted, and that she was a traumatized young woman perhaps nudged in the wrong direction by a justice system that had already treated Broadwater with suspicion.

But the gaps in the memoir are undeniable. Besides the hair analysis, which has since been proven to be junk science, she seems unable or unwilling to recognize the possibility that she may have been identifying the wrong person.

Even when she sees Broadwater on the street — she gives him the pseudonym Gregory Madison in the book — it’s not clear how she could have known he assaulted her. She initially doesn’t even see his face: “The black guy I could see only from the back, but I was hyperaware. I went through my checklist: right height, right build, something in his posture, talking to a shady guy.” She identifies him only after he approaches her with a smile and asks if they’ve met before. She calls the police, and a cop drives around with her to try to find him. After he sees three young Black men, none of whom match her description, he jumps out of his car. “They’re troublemakers,” he says before chasing after them with a billy club. He returns later, sweating. “Open container,” he says. “Never talk back to an officer.”

Her identification of Broadwater in a police lineup is also problematic. She picks out the wrong man (though, arguably, identifying Broadwater would have also been incorrect) because she thinks two of the men in the lineup look “identical.” Her sketch of her assailant didn’t match Broadwater. During her attack, it was dark, and her glasses were knocked off. There is, at minimum, reasonable doubt.

Sebold makes some attempts to show how she knows there’s a power imbalance between a white woman and a Black man within the justice system. Of the cop chasing after three men with a billy club, she writes, “It was wrong to hassle, and perhaps physically hurt, three innocent young black men on the street. There is no but, there is only this: That officer lived on my planet.” She recognizes that the cops saw her as a peer, as someone to protect, in a way they seemingly didn’t view Broadwater. She knows and repeats, again and again, that she was a “good girl,” that she was a “good” victim, that she did a “good” job telling the court what happened to her. She’s so fixated on being good, and on helping the police get the bad guy, that she maybe couldn’t see her role in a system designed to punish innocent Black men like Anthony Broadwater.

What Lucky did best — and this is also its chief flaw, then or now — is describe what it looks like when the justice system functions “well.” It’s a nice fantasy, one that feels reminiscent of Law & Order: SVU episodes when Olivia Benson pulls out all the stops for a young, brutalized woman, but it’s a fantasy all the same. Even with the false conviction, Sebold was a rarity. Most women do not report their rapes, few are believed, and even fewer go through a trial. She refers to one of the detectives in her case as “fatherly,” even though he’s gruff and cold with her at the beginning of the memoir. The bailiff in her case praises her for being “the best rape witness [he’d] ever seen on the stand,” a statement she says she carried with her for years. But what she neglects to mention is that in order to be a “good rape witness,” there are bad ones, ones who can’t or don’t allocute precisely and convincingly, ones who aren’t considered sympathetic by a jury.

Broadwater spent almost a third of his life in prison, and Sebold is a rape survivor with no closure.

Sebold was supported by the justice system. She had a lot of people on her side. It’s clear that she identified the wrong Black man in her case, but it’s also clear that the justice system encouraged her to do so. There’s no doubt at all that she was raped or that the details she recounts of that night are true. It wasn’t her responsibility to manage how the case was being investigated — that was the responsibility of the police, who likely wanted to move expeditiously to get a conviction, and the responsibility of the state, who prosecuted Broadwater with the questionable evidence they had. She is responsible for pointing her finger at an innocent man, but she’s only one element of a larger failure. The way this has shaken out has given justice to no one; Broadwater spent almost a third of his life in prison, and Sebold is a rape survivor with no closure.

But there’s another story to tell, from Broadwater’s perspective. What ran through his mind when he said hello to a white woman near campus and was quickly apprehended for a rape he never committed? How did he react to being told his pubic hair matched the hair found on that woman, even though they had never actually had contact before? How did he manage every one of those 16 years without parole? And how did he process spending decades on the sex offender registry — isolated from family, unable to move through the world with freedom? “On my two hands, I can count the people that allowed me to grace their homes and dinners, and I don’t get past 10,” Broadwater said after his exoneration. “That’s very traumatic to me.” He’s had more empathy for Sebold than you might expect: “I sympathize with her. But she was wrong.”

In her statement, Sebold wrote, “40 years ago, as a traumatized 18-year-old rape victim, I chose to put my faith in the American legal system.” She added, “I will remain sorry for the rest of my life that while pursuing justice through the legal system, my own misfortune resulted in Mr. Broadwater’s unfair conviction for which he has served not only 16 years behind bars but in ways that further serve to wound and stigmatize, nearly a full life sentence.” The details of Sebold’s assault and resulting PTSD are still powerful, but so much of the book hinges on a credulous faith in a corrupt justice system. In 1999, Lucky was a book about a young woman reckoning with brutality and coming out the other side, alive and restored.

Now, it’s a horror story. ●