This is an excerpt from Quibbles & Bits, the BuzzFeed News copy desk’s newsletter. Sign up below to nerd out about language and style with us once a month!

For BuzzFeed News’ Body Week, the copy desk is looking at the language we use when we write about bodies, particularly fat bodies. It’s always been at the core of our style guide to avoid any sort of body-shaming, and we’re always learning when it comes to what words people want to use to talk about their bodies — when it’s relevant to talk about them at all.

As always, we avoid euphemistic language. Unless someone describes themself as “chubby” or “full-figured,” we’re never going to refer to them as such. There’s nothing wrong with “fat.” The word itself is just a descriptor, but a society that praises and elevates thinness has tried to make “fat” so negative that people opt for terms they believe are based in medicine, like “overweight” or “obese.” But they fail to take a step further and question what’s really behind those words and what stigmas they perpetuate.

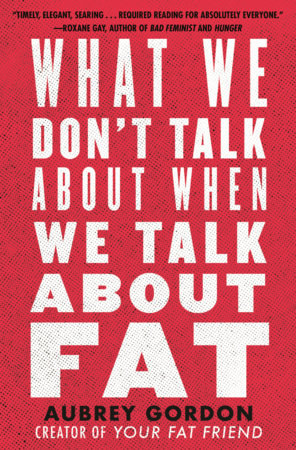

People say “obese” and “overweight” under the guise that they are discussing someone’s health rather than their appearance, but this vocabulary insidiously upholds anti-fat bias. “Overweight” implies that there is some objective standard weight by which we can assess the health of every body. And “obese” comes from the Latin “obesus,” which means “having eaten oneself fat,” a definition that activist and writer Aubrey Gordon describes as “inherently blaming fat people for their bodies” in her book What We Don’t Talk About When We Talk About Fat.

“Obesity” is a category people fall into based on their body mass index (BMI), a metric that has come up frequently in the last two years of the pandemic; the CDC claimed that it indicates a higher risk for severe COVID-19, and one’s BMI measurement qualified some to get the vaccine earlier than others. As a copy desk, we had a discussion about person-first language when it comes to “obesity” (e.g., “person with obesity”), but the truth is the term itself is best avoided. BMI doesn’t measure anything about an individual’s health — it simply looks at height and weight and is based on a Belgian scientist’s idea of “the average man” 200 years ago. It’s racist and served as a steppingstone to the creation of eugenics. And both “obesity” and “overweight” have contributed to weight stigma that leads to employment discrimination and physical and mental health issues.

Gordon, also known as Your Fat Friend, has written endlessly on this subject, and her book dives into the pervasiveness of anti-fat bias in society and its incredibly detrimental effects. In an essay for Self, she explains why she uses the words “anti-fatness” and “anti-fat bias” to discuss “the attitudes, behaviors, and social systems that specifically marginalize, exclude, underserve, and oppress fat bodies.” These terms, she writes, are clear about who is being hurt under this societal dynamic, and they denote an active discrimination as opposed to a legitimate fear, as suggested by the word “fatphobia.” (We follow a similar guidance on the suffix “-phobia” and try to use “anti-” constructions since we’re usually talking about a prejudice rather than a psychological disorder.)

Even in our own copyediting, there have been times when we’ve opted for “body-shaming” when we really meant “anti-fat.” This is perhaps reflective of how ingrained it is in us to avoid language that makes us uncomfortable or to cower to the vernacular of a body positivity movement that still centers thin bodies and isn’t honest about the ways fat people are really under attack. Of course, we also want to use the language that people use to describe themselves, and sometimes doing so leads us to avoid words like “fat,” which society has trained everyone to read as pejorative. But there’s a stark difference between sensitivity and euphemism.

“Fat justice” is how Gordon describes the goal of her work. “I yearn for more than neutrality, acceptance, and tolerance,” she writes in What We Don’t Talk About When We Talk About Fat, “all of which strike me as meek pleas to simply stop harming us.” As with any movement for justice, language is only a small part of it, but it matters.

That’s why when we reference clothing sizes, we use the terms “straight-size” and “plus-size.” We don’t use words like “normal” to describe people or their bodies.

So, as always, think about the words you’re using to talk about people’s bodies, and also why you’re talking about bodies in the first place. Do the physical descriptions in your story add color, or are they reminiscent of a tabloid headline? Does your choice to describe one body and not another affect how your reader perceives your subjects and sources in ways you didn’t intend? Did you avoid a word that made you uncomfortable and replace it with one that fails as an accurate description?

We’ll keep striving to use neutral language when writing about people’s bodies and, perhaps more importantly, asking ourselves if it’s even relevant.

What’s the Word?

glabella \gluh BEH luh\ (noun) The area between your eyebrows. According to Merriam-Webster, its first known use was in 1823, and it descends from the Latin “glabellus,” meaning “hairless” (although “eyebrowless” might be more accurate).

This is where you see frown lines (or “elevens”) from furrowing your brow and squinting. Wrinkles that form in the glabella are known as “dynamic wrinkles” because they are caused by muscle contractions — which injections of Botox, or botulinum toxin, can temporarily paralyze or relax.

Used in a sentence: My glabella is so smooth that you can’t tell how furious I am that I spent so much on Botox last week.

–

What We’re Reading

BuzzFeed News: “Suffixes Have Been Slang-ified”

Slate: “How the Russian Invasion of Ukraine Is Playing Out on English, Ukrainian, and Russian Wikipedia”

Mother Jones: “There Are Many Words for Vladimir Putin. Is ‘Strongman’ One?”

The Atlantic: “The Two Most Dismissive Words on the Internet”

The Washington Post: “Did a Faulty Pronoun Really Cancel Catholics’ Baptisms, Marriages, Confessions?”

And finally, a tweet:

I don’t proofread my tweets before sending because I’m a copy editor and I don’t work for free

This story is part of our Body Week series. To read more, click here.