WASHINGTON — Harry Reid, the former Senate majority leader and five-term senator from Nevada, died Tuesday. He was 82.

His wife, Landra Reid, said he died surrounded by family following four years of treatment for pancreatic cancer. Reid underwent surgery for pancreatic cancer in May 2018 and had said in 2020 that he was in “complete remission” after experimental treatments.

“We are so proud of the legacy he leaves behind both on the national stage and his beloved Nevada,” she said in a statement.

His death was immediately heralded by his longtime Senate colleagues.

“He’s gone but will walk by the sides of many of us in the Senate every day,” Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer tweeted.

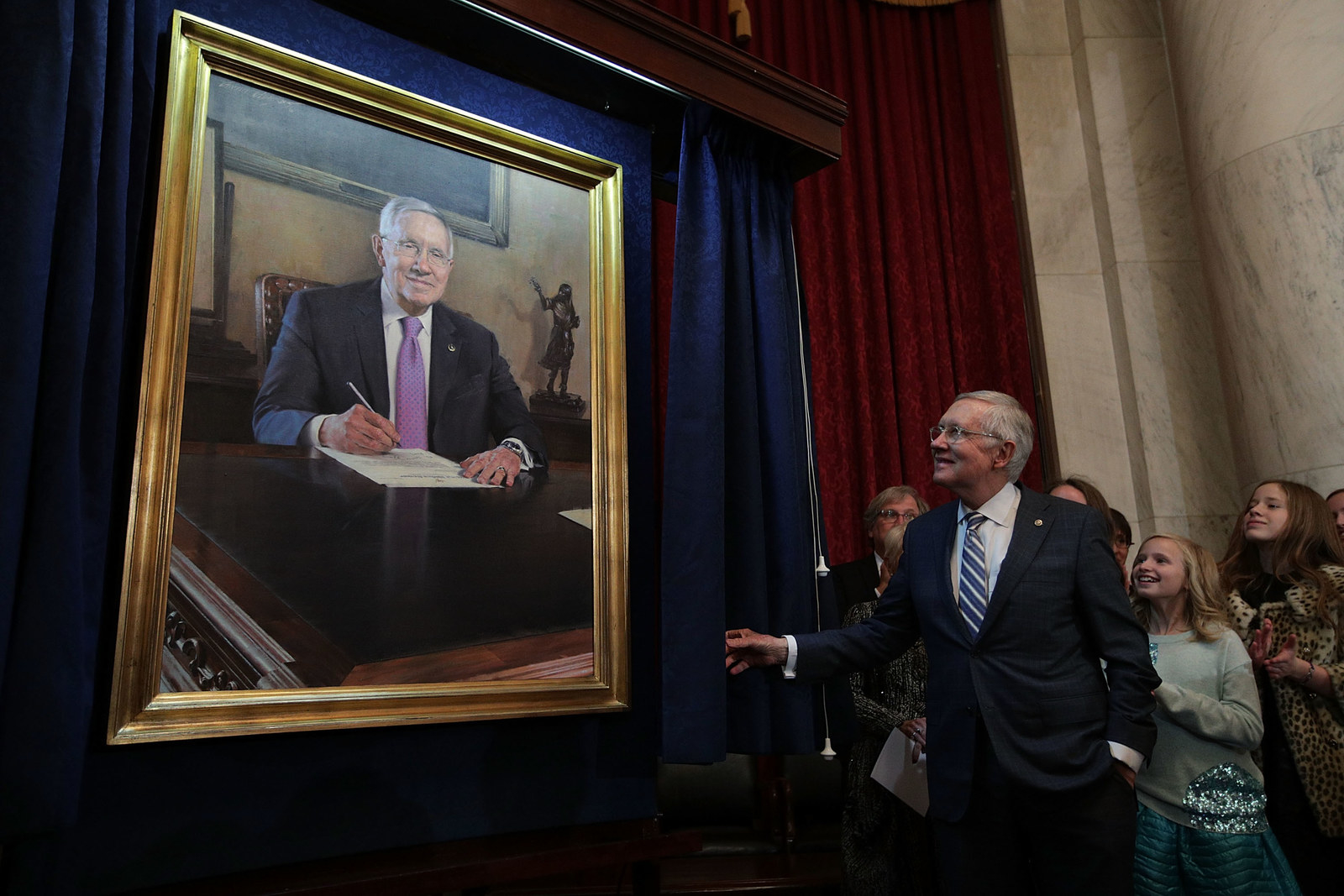

Reid, who grew up poor in the tiny mining town of Searchlight, Nevada, worked his way up to the top Democrat in the Senate. A chess master of Senate procedure and political kingmaker in Nevada, Reid retired from Congress in January 2017, but he continued to be involved in politics. In the 2018 midterm elections, Reid hand-selected Democratic candidates for Senate and governor — now-senator Jacky Rosen and current governor Steve Sisolak.

With more than 30 years in Congress, Reid has been synonymous with Nevada politics for decades. The international airport in Las Vegas was officially renamed after him just this month.

Reid was first elected to the US House in 1983, serving two terms before running for Senate in 1986. Over the next three decades, he rose through the ranks of Democratic leadership, eventually becoming the party’s top leader in the chamber in 2005.

For just over a decade, he and Mitch McConnell traded off the titles of majority leader and minority leader as their parties took control of the Senate. The two men had a contentious relationship that was built not solely on antagonism, but also on a grudging respect. They considered each other friends, despite years of bitter legislative battles.

As McConnell noted when Reid retired, the two senators had a lot in common, despite their strong political differences, including having similar ambitions growing up. “I wanted to throw fastballs for the Dodgers. Harry wanted to play center field at Fenway. We wound up as managers of two unruly franchises instead,” he joked.

View this video on YouTube

Mitch McConnell's tribute to Harry Reid upon the latter's retirement.

Reid compared their relationship to two lawyers — which both were prior to entering Congress — arguing opposite sides of a case. “I want everyone here to know that Mitch McConnell is my friend. ... So everybody go ahead and make up all the stories you want about how we hate each other. Go ahead. But we don't,” he said.

Senate Accomplishments

Reid served for 12 years as Democratic leader, one of the longest-serving party leaders in history. In that time, Reid oversaw many deals and failures. Among his personal highlights, he noted his work on suicide prevention, inspired by his own father’s suicide; his push to pass the Congressional Review Act, which allows Congress to overturn recent executive branch regulations (McConnell later used this to rescind several late–Obama administration actions); and his fight to combat female genital mutilation (though he noted on FGM, “There's a lot more that needs to be done. Our government has done almost nothing.”).

But Reid’s biggest legislative victory was passing the Affordable Care Act in 2010. Not only was the law the largest overhaul of the US healthcare system since Medicare and Medicaid, it took a lot of legislative maneuvering to get through Congress, much of it led by Reid and his House counterpart, Nancy Pelosi — particularly after Sen. Ted Kennedy died and was replaced in the middle of the process by Republican Sen. Scott Brown, killing Democrats’ filibuster-proof majority.

Reid often spoke of Obamacare as a major legislative achievement, but also a personal one. “It would have been wonderful if we had something like that around to help my family when we were growing up,” he said as he retired in 2017, also noting that his father’s depression played a role in his push for better healthcare.

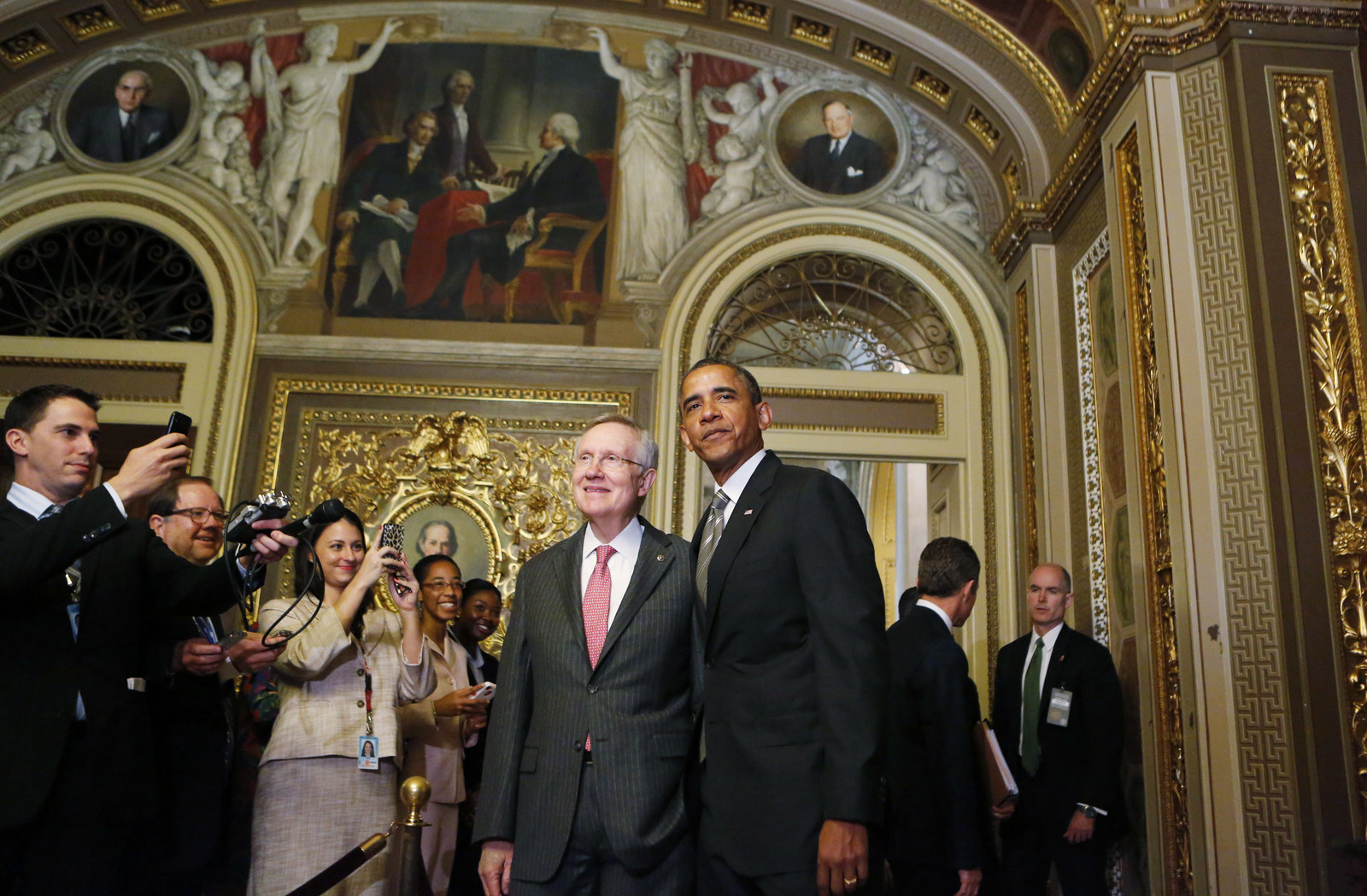

Reid was close with Obama as well and took credit in a CNN interview as the first to suggest to the then–Illinois senator that he should run for president. “I called him into my office and told him he should take a look at it. He was stunned because I was first to suggest it to him," Reid told the network. “When he was reelected I got a call saying, ‘As soon as he gets off the stand, he wants to talk to you.’ One of most moving phone calls ever received, he said, ‘You're the reason I'm here.’”

"I care about Obama. He changed the world," he added.

In his farewell address, Reid said that working with the Obama administration as majority leader was a “dream job.”

On Tuesday, the former president shared a letter he had written Reid before his death.

“You were a great leader in the Senate, and early on you were more generous to me than I had any right to expect,” Obama wrote. “I wouldn't have been president had it not been for your encouragement and support, and I wouldn't have got most of what I got done without your skill and determination.”

Yet perhaps Reid’s most lasting effect on the Senate itself was his decision to invoke the “nuclear option” in November 2013, allowing the Senate to move administration officials and judges forward with a simple majority rather than 60 votes needed at the time for cloture. At the time, Reid argued that lowering the number of votes needed to confirm federal judges and nominations to the executive was necessary to end constant Republican filibusters. (He later told CNN, however, that he was inspired in part by New York Sen. Chuck Schumer telling him that Republicans were mocking him, saying he’d never go through with it.) The gambit worked in some ways; after dropping that bomb in the Senate, Reid pushed Obama’s nominees for lifetime judgeships, leaving the president with 334 successful nominations, roughly as many as former president George W. Bush had gotten through during his presidency.

But the nuclear option had its drawbacks as well, and there were critics of Reid’s decision in both parties even at the time. McConnell used that rule change to confirm even controversial members of former president Donald Trump’s cabinet and to jam through lower court judges. And in 2017, as many predicted, McConnell went nuclear himself — lowering the number of votes needed for Supreme Court nominees as well, which allowed Republicans to confirm Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett to the high court.

While Reid’s decision to go nuclear laid the groundwork for McConnell’s expansion, some liberals argued Reid was wrong not to expand the rule change to the Supreme Court himself when Republicans refused to confirm Merrick Garland, who Obama had nominated in 2016. On the other side of the argument were Democrats like Schumer, who opposed going nuclear for executive branch nominees and came to regret the rule change after it was applied to Trump’s cabinet.

Reid defended the decision, even after Trump was elected, writing in a December 2016 New York Times op-ed that “the rule change has been a victory for those who want to see a functioning, open and transparent Senate.”

“I doubt any of us envisioned Donald J. Trump’s becoming the first president to take office under the new rules. But what was fair for President Obama is fair for President Trump,” he wrote.

Reid announced in 2016 he would retire, handing the reins over to his longtime mentee, Schumer. Reid told the New York Times at the time, “I want to be able to go out at the top of my game. I don’t want to be a 42-year-old trying to become a designated hitter.”

Controversy and Fighting With Republicans

Though he was soft-spoken, Reid could be brash and tough, showing flashes of what drove him as an amateur boxer in his youth during political bouts. He was a constant antagonist of the Republican Party, often skirting the truth to attack the right. Famously, in the 2012 presidential race, Reid claimed in a speech on the Senate floor that Mitt Romney, who released only two years of tax returns, hadn’t paid any taxes in a decade.

That was a lie. And even years later, Reid wasn’t sorry about it. When asked if he regretted making the accusation, Reid told CNN in 2016, “Well, Romney didn’t win, did he?”

Republican megadonors the Koch brothers were one of Reid’s favorite targets and most hated enemies. He devoted lengthy speeches to the brothers, calling their dark money investments in politics bad for the country and he relished using the line “Republicans are addicted to Koch.” Friends said his fixation on the Kochs was political — he’d later argue no one on the Democratic side was doing enough to counter the Kochs, so he just did it himself — but also personal; he felt very deeply that the Supreme Court's Citizens United decision loosening restrictions on money in politics was doing damage to the country and the Kochs were the biggest symbols of that.

But Reid wasn’t as harsh toward Sheldon Adelson, another Republican megadonor who just happened to hail from Nevada. Reid once argued to MSNBC that Adelson, unlike the Kochs, wasn’t “in this for money.” “He’s in it because he has certain ideological views,” he added. “His social views are in keeping with the Democrats on choice, on all kinds of things. So, Sheldon Adelson, don’t pick on him — he’s not in it to make money.”

Early Life

Before entering Congress, Reid’s life was straight out of a movie script. (He even inspired a scene in the movie Casino, which lifts some of Reid’s own lines.) He was born in Searchlight, a tiny town in the desert, and grew up in a house with no indoor plumbing. His father was a miner and his mother was a washer who cleaned clothes for the local casinos and the 13 brothels operating in the town of 250 people at the time, he often recalled.

As he grew older, Reid became an amateur boxer and, as he acknowledged later in life, got into plenty of fights outside of the ring as well. In 2018, he was inducted into the Nevada Boxing Hall of Fame both for his own fighting career and for his advocacy for the sport while in the Senate.

He graduated college from Utah State University and later got his law degree from George Washington University. While in law school, Reid earned money by serving as a Capitol police officer, guarding the building he would later preside over.

Reid’s father killed himself in 1972, a death that informed a lot of his later policymaking. He cited his father’s suicide in his push for increased funding to study depression as well as for suicide prevention efforts, but also in making his case for increased background checks for gun sales, as well as for the Affordable Care Act.

In the late 1970s, Reid was appointed as the chair of the Nevada Gaming Commission, a powerful position where he oversaw the state’s casinos, which had a major mob influence at the time. In 1978, a Las Vegas man named Jack Gordon tried to bribe Reid to approve new gaming machines — an attempt that led to one of the more famous confrontations of Reid’s pre-political career. Reid reported the bribe to the FBI and worked with them on a sting to ensnare Gordon. Much to the surprise of FBI agents, when Reid met with Gordon, he grew increasingly angry and jumped across a table to choke the man, screaming, “You son of a bitch, you tried to bribe me!” before agents pulled him off and arrested Gordon.

Three years later, Reid’s wife, Landra, found a car bomb attached to the gas tank of the family’s station wagon. Reid, who wrote about the incident in his autobiography The Good Fight, believed that Gordon was responsible. Gordon had spent six months in prison after the FBI sting Reid arranged but was never officially connected to the car bomb. It’s still unclear who was responsible.

In 2015, Reid’s colorful past came back to haunt him in a bizarre conspiracy theory. The Senate Majority Leader had fallen after an exercise band snapped and threw him backward, causing him to break several ribs and injuring his face. He nearly went blind in his right eye and returned to Capitol Hill with a massive bandage over it that he later swapped out for dark sunglasses as he recovered. (Reid and his wife later sued the manufacturer of the exercise band.)

But some conservative blogs and right-wing pundits didn’t buy the exercise band story and offered — without evidence — an alternative. One conservative blogger, citing a friend who had visited Las Vegas and asked around, suggested that Reid had been beaten up by the mob for not coming through on some kind of promise. Rush Limbaugh also said Reid looked like he’d been beaten up and said he didn’t believe the exercise band story. Breitbart went so far as to reconstruct Reid’s bathroom in detail from sales photos of the property in an attempt to disprove his story.

Reid responded to the conspiracy theories in a CNBC interview, calling them ridiculous and largely blaming Limbaugh. “Why in the world would I come up with some story that I got hurt in my own bathroom with my wife standing there?” he asked.

Family Life

Reid is survived by his wife, Landra, whom he met in high school and married at the age of 19. He has often described her as his first love and the love of his life. The two have five children and 19 grandchildren.

In his tribute to Reid on the Senate floor in honor of his retirement, McConnell spoke at length about Reid’s relationship with his wife. “His idea of the perfect night out is still a quiet night in, with her,” McConnell said. “Landra’s his confidante, his high school sweetheart, his best friend. She’s his everything. And, for a guy who grew up with nothing, that’s something.”

Landra had grown up Jewish (though she and Reid later converted to Mormonism), and her father opposed their marriage. At one point, Reid punched his future father-in-law in the face and Landra and Reid ended up eloping, though Reid said her family accepted them over time.

In his own farewell speech on the Senate floor, Reid paid tribute to his wife, saying, “She has been the being of my existence, in my personal life and my public life. [Benjamin] Disraeli, the great prime minister, said in 1837: ‘The magic of first love is that it never ends.’ I believe that. She's my first love. It will never end.”

Reid, in his speech, also shared the advice he had given to young people asking how to emulate his success. “I didn't make it in life because of my athletic prowess. I didn't make it because of my good looks. I didn't make it because I'm a genius. I made it because I worked hard, and I tell everyone whatever you want to try to do, make sure you're going to work as hard as you can at trying to do what you want to do. And I believe that's a lesson for everyone,” he said.

“The little boy from Searchlight has been able to be part of a changing state of Nevada. I'm grateful I've been part of that change.”