Fast-fashion chains like Forever 21 and H&M have transformed the American clothing industry in the past decade, pushing consumers to expect ever-lower prices on a constantly revolving array of styles.

But Primark, the latest entrant to the game, plans to go even cheaper in a world already populated by $10 sweaters and $4 leggings.

The Irish retailer has said its mission is "delivering Forever 21 fashion at a Walmart price," Goldman Sachs analysts wrote in a note on Sept. 15, without a hint of irony. At Primark first U.S. store, which opened in Boston in September, shoppers will find $7 jeans, $8 sweaters, $3.50 t-shirts and tanks tops for $1.60.

The store, the first of at least eight planned to open in the U.S. Northeast by next year, has four floors and measures 77,000 square feet; it has neon signage, video boards and phone charging stations and is, apparently, well organized.

Prices are about 40% lower than H&M's and 75% cheaper than Gap Factory, the Goldman analysts wrote — so cheap they can't be sold online. An analyst from Cowen & Co. referred to Primark as "fast fashion 2.0," while another analyst from KeyBanc predicted the chain will be "highly disruptive" to American retail in coming years.

Primark's willingness to sell t-shirts that cost less than a Big Mac illustrates how relentlessly apparel prices in the U.S. have declined in recent years. (A Big Mac cost an average of $4.79 in July.) Retailers are increasingly shuttering regular stores and expanding outlets, where they can sell a discounted version of their own brand; others, like Macy's and Nordstrom, are seizing on low prices by investing in off-price, T.J. Maxx-style chains.

Primark could be seen as the final frontier of this low-price, high-consumption cycle: it relies on massive volumes in giant stores to turn a profit on the cheapest threads, in the ultimate bet that consumers will prioritize price above all. Shoppers are encouraged to show off their new looks and how little they paid for them on the popular "Primania" section of its website. Lower quality accounts for some of Primark's prices — more polyester in jeans, less trim on tops — but that's not a "significant issue" for consumers, the Goldman analysts wrote.

It's striking that price wars remain rampant even now, especially amid growing recognition that cycling through disposable clothing is bad for the environment and often worse for the workers making it. Patagonia and startups like Everlane and Zady have urged consumers to shop less and more thoughtfully, as have books (Overdressed), documentaries (The True Cost) and TV shows (this bit by HBO's John Oliver comes to mind.) One of the hot lifestyle trend this year has been "de-cluttering," as prescribed by Marie Kondo.

"There are two extremes happening," said Liz Dunn, CEO of retail consulting firm Talmage Advisors. "There is this complete consumption bubble but at really cheap prices, buying more and more things for less and less money...and this whole capsule dressing, limited wardrobe, really responsible approach that's gaining a lot of momentum, too."

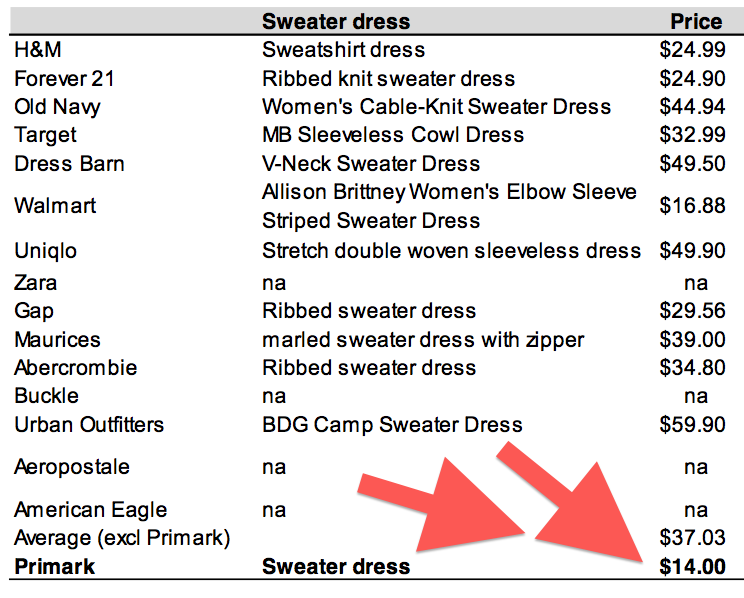

One of KeyBanc's charts shows a sweater dress costs $14 at Primark, compared with $30 at Gap, $50 at Uniqlo and $25 at H&M.

Price doesn't correlate with responsible sourcing, but it does raise questions at the low end. When Forever 21 introduced its cheaper, basics-oriented F21 Red chain last year, it cast a spotlight on the human cost behind $1.80 camisoles and $7.80 jeans. Allan Ellinger, a senior managing partner at MMG, an investment bank and restructuring advisor, told BuzzFeed News at the time that it was impossible for such clothing to be made in a humane way on a sustainable basis. Now, Forever 21 says they have 20 F21 Red stores.

Primark says it's able to operate ethically and profitably at rock-bottom prices by ordering in bulk and sourcing fabric near manufacturers. It also says it avoids big ad campaigns, focuses on popular sizes, and uses factories in the off-season.

"Primark's prices are low because Primark operates differently than other retailers, reducing its costs by working smart and lean," a spokeswoman told BuzzFeed News. "In turn this saving is passed on to its customers."

But the retailer was one of the biggest brands linked to the collapse of Rana Plaza in Bangladesh in 2013, a tragedy that left more than 1,100 dead and injured more than 2,000. Primark made payments directly and to dependents of the 688 workers who were injured or killed at its supplier, New Wave Bottoms, and revamped its policies in the country.

Primark has also been accused of overlooking unauthorized subcontracting by its suppliers. Some customers claim to have found messages seeking help sewed into their clothing from desperate factory workers. Primark features extensive literature online describing its efforts to source responsibly, saying it inspected more than 2,400 factories last year.

"We place the utmost importance on the well-being of workers in our supply chain," the Primark spokesperson told BuzzFeed News. "We thoroughly investigate the circumstances surrounding any allegation, but sadly Primark has been the subject of hoax labels in the past. Primark takes the standards in its supply chain very seriously, and we work hard to ensure our products are made in good working conditions, and that the people making them are treated properly and paid a fair wage."

While an eight-store base next year would be small, the Goldman analysts estimated that Primark could grow bigger than Abercrombie & Fitch and Hollister in one full operating year, assuming the locations are 75% as productive as its European counterparts.

If Primark is right about what consumers want, it's easy to see why that's terrifying for traditional retailers like Gap and Abercrombie & Fitch — and for apparel, in general.

"All of the merchandise in Gap Factory's women section could barely have filled Primark's shoe section," Erika Adams wrote for Racked after visiting the new Boston store this month. "Red sale signs were hanging over nearly every item on Gap Factory's floor, but even at 60% off, those $59.99 jeans no longer looked like a steal. Tank tops advertised at $19.99 apiece suddenly seemed wildly expensive compared to the $6 neon printed ones I'd just held across the street."

Dunn, of Talmage, senses a reckoning on the horizon.

"A lot of companies are trying to do things ethically and trying to put in compliance in their factories to make sure these things are not happening," Dunn of Talmage said. "That could be a way for a company to maybe stand out and compete against these low, low prices that sort of necessitate really horrible working conditions."

"Everything about it tells me there will be some backlash — but it's like, will it be this year? Will it be five years from now?"