Robert Hanson's arrival in 2012 as the new CEO of American Eagle Outfitters symbolized a new dawn for the preppy teen retailer.

Smooth and charismatic, he swooped into the steel city of Pittsburgh from San Francisco, where he was the president of Levi's, with big ideas on how to update American Eagle for the digital age and win back teenagers from rapidly rising fast-fashion retailers such as Forever 21 and H&M. He was a quick hit with Wall Street and even more popular with employees, especially younger ones, who felt as if American Eagle had been imbued with a new energy and vision. Hanson, 49 at the time, replaced Jim O'Donnell, a 71-year-old CEO who planned to retire after almost a decade in charge. It was a major shift for the retailer, which spent the better part of 2011 looking for the right person.

So it was utterly shocking to employees and observers of American Eagle when Hanson was abruptly fired in January, just eight days shy of his two-year anniversary with the retailer. American Eagle didn't explain the decision beyond a brief statement noting that the company's chairman would assume the role of interim CEO until a successor was found. Employees reeled, shares spiraled, and questions swirled.

Hanson's ouster, it turns out, was the result of a bitter clash with a handful of longtime executives who ultimately campaigned against him behind the scenes, according to interviews with nine current and former employees who spoke on the condition of anonymity. These sources describe American Eagle as an insular company that hired Hanson to transform the retailer for a new generation of teenagers, only to balk at changes he made to reach that goal, especially when it came to bringing in new executives. Divisions grew as it became clear the two camps held different views on the future of teen retail and how American Eagle fits into that picture.

Sources said Hanson's biggest obstacle was Roger Markfield, American Eagle's 72-year-old executive creative director. The executive, who is also a board member and close friend of Chairman Jay Schottenstein, was supposed to follow O'Donnell into retirement in February. But as the business struggled last year, along with most other teen retailers, Markfield actually grew more involved, blaming Hanson for not paying enough attention to merchandise and stores, which were the twin hallmarks of the American Eagle brand in the '90s and early 2000s. Their relationship grew "extremely combative," one former executive said — a dangerous development given Markfield's sway at the company and with Schottenstein. Fred Grover, an executive vice president who joined American Eagle in 1978, and chief marketing officer Michael Leedy, who worked there from 1994 to 2006 and returned in 2011, joined Markfield in leading a coup against Hanson in January, sources say.

With Hanson gone, Markfield has postponed his retirement and reasserted control of the company; two other former executives speculate that Grover, too, is no longer planning to retire later this year. Two sources say that internally, Markfield is viewed as acting CEO even though he's based in New York. There is precedent at the retailer for having a remote CEO: When Schottenstein, a wealthy entrepreneur who's also chairman of DSW, was American Eagle's CEO in the '90s, he worked remotely from Columbus, Ohio. In recent months, a former executive said the company's top brass has flown to Florida for meetings aboard Schottenstein's yacht, rather than convening in Pittsburgh. Inside the company, employees are worried that American Eagle is heading backward.

American Eagle declined to comment for this story through spokeswoman Iris Yen after BuzzFeed described the article and reporting in a phone call and subsequent emails. She noted the board has said all it would like to on the issue.

American Eagle is the middle sibling of the "three A's," the retail industry's nickname for a group that includes the company, Abercrombie, and Aeropostale, all of which rose to prominence by selling different-priced versions of the same preppy styles to high school and college kids. When Hanson's predecessor became American Eagle's CEO in 2002, teens in the U.S. were all about the uniform look and hanging out in malls. E-commerce and fast fashion were blips on the horizon, evidenced by the fact that American Eagle was still opening lots of stores across the U.S.

By the time O'Donnell announced his plan to retire, nine years and one recession had passed. So, too, had American Eagle's ascent. H&M and Forever 21 had burst onto both the cultural and business scenes in a big way, teens' tastes were shifting from graphic tees and performance fleeces, and technology had advanced dramatically. There was new pressure on the three A's, along with other once-hot teen retailers from PacSun to Wet Seal, which persists today.

American Eagle spent months looking for O'Donnell's replacement before choosing Hanson, a tall, confident, good-looking and, most importantly, accomplished executive. In his 23 years at Levi's, Hanson helped revitalize and build the denim brand into a $3.5 billion business, making him seem like an ideal fit for American Eagle, which is roughly the same size.

Hiring an outsider was a bold and decisive move for American Eagle, since many of its top executives had worked their way up from inside the company and had been friendly for years, giving off an "old boys' club" feel, at least at the highest ranks. By contrast, Hanson came from San Francisco, where he was a prominent member of the LGBT community, and worked in Europe before that, leaving some employees with the impression that he was intimidatingly cosmopolitan for the company, two former managers said.

"Mostly everybody that holds significant roles has actually grown up within the company, which you could say is a good quality, but it also tends to show you they have a hard time adapting to or embracing other company cultures," said one of the former managers.

Still, all nine sources agreed the vast majority of employees were excited by Hanson's arrival, with most adding that he swiftly altered its corporate culture for the better, both at 77 Hot Metal Street in Pittsburgh (an homage to the year American Eagle was founded) and in New York. On his first day, for example, he walked around the office shaking hands and introducing himself to employees of all ranks, a warm and approachable presence sources said he maintained throughout his tenure. Hanson sought to keep workers connected through more frequent companywide emails and town hall meetings, and started new traditions like a community volunteer day and sponsoring Pittsburgh Pride week — causes that mattered to American Eagle's customer base. He even introduced a shuttle between American Eagle's headquarters and its New York design office to ease travel for grateful staffers, rarely flying his corporate jet between the two cities without filling it up with associates, two sources said.

"I would not say there was much of a culture to speak of, or one you were proud of when I started, and I think that was a big part of what he was trying to do," said the other former manager. Added another employee, who worked in marketing: "If you were ever in an elevator, he always had a great conversation with you. The people before were never like that. They were just kind of like, 'We're C-level execs, you guys just work for us' kind of mentality."

Financially, Hanson's first year was a smashing success — annual sales rose to a record $3.5 billion and adjusted profit soared as the retailer managed leaner inventories and cut product costs while also scaling back on markdowns. He sold off the flailing 77Kids business to focus on AE and Aerie, the booming intimates chain introduced in 2006. At the end of the year, employees got a double bonus and investors were giddy after seeing shares rise a whopping 34%, more than twice the increase in the S&P 500.

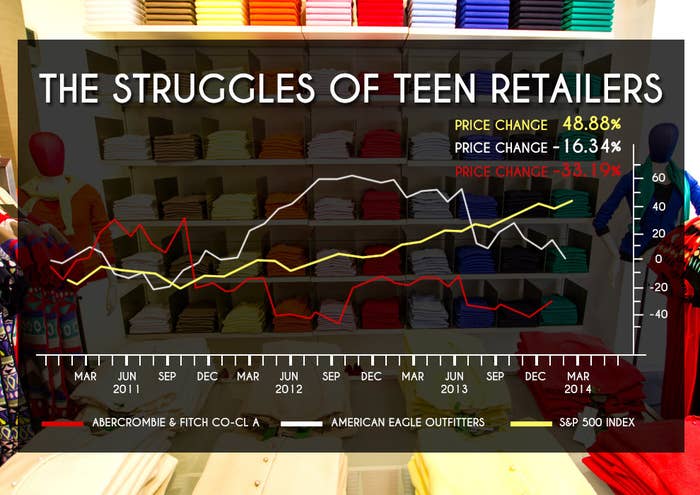

But the business took a turn for the worse last year. Starting with the first quarter, earnings consistently fell short of expectations, as American Eagle's clothes and marketing failed to connect with consumers. It was a brutal year for many of American Eagle's rivals as well, with everyone from Urban Outfitters to Abercrombie & Fitch feeling the effects of high teen unemployment, declining mall traffic, and miserable weather throughout the course of the year. Most of the stock gain was given back, with shares falling 30%.

Three former executives said the old regime seized on the bad numbers to cast Hanson's tech-focused ambitions in a dubious light. They said Markfield, in particular, felt that Hanson cared too much about developing AE's web and mobile operations, and feared that expanding in outlets and internationally, while lucrative, might dilute the core brand. Markfield was also no fan of Hanson's emphasis on personalization — for example, curating merchandise in stores based on the type of customers who shopped there. Indeed, it was a relatively new way of doing things, especially for someone who came of age in retail during the '80s and '90s and considered a mainline store as the most important way to communicate a brand. Markfield felt those stores were being neglected, these people said.

Photos from the volunteer day Hanson introduced.

And then there was the problem of the San Francisco office.

After spending time in Silicon Valley, Hanson believed that opening a satellite office in the Bay Area was the best way to hire top tech talent to build out American Eagle's website and harness customer data to support its East Coast teams. He moved one of his new hires, Joe Megibow, who previously worked at Expedia, out West to head up a new 10,000-square-foot office. In a July 2013 release announcing the venture, American Eagle said it planned to hire as many as 100 new employees within a year. It was ambitious, but it wasn't insane — retailers from Macy's to Wal-Mart have set up offices in California for precisely the same reasons.

But the decision rankled many in the Pittsburgh office who took offense to the idea that such talent couldn't be found in their city. After all, many employees either grew up within the company or had roots in Pittsburgh. Plus, the venture was really expensive. Information technology and e-commerce investments totaled $81.6 million last year, or 30% of American Eagle's capital expenditures. In 2012, total capital expenditures were about $94 million.

"The sense was, 'Oh, there's this new fancy office in San Francisco, these fancy people have engineering backgrounds from Stanford, where does that leave me?'" said the second former manager. "People just felt threatened and unsure of it, definitely for the executives, because it was Robert bringing on this team of strong executives to fix and do things that we needed to do."

It also highlighted the philosophical divide between Hanson and the old guard, especially Markfield. As one current employee put it: "A lot of people don't feel like the stores are anything to think of anymore because everyone shops on phones or online, and those are things that are definitely not within Roger's scope. Those were concerns of Robert, which is why he built the SF team. He thought, If we don't get this right now, we won't be relevant in five years at all, and I think that's the truth."

As the numbers continued to deteriorate throughout the year, tensions increased between Hanson and a small group of senior leaders who preceded his arrival, some of whom feared getting pushed out. Many felt that they didn't have to respect him as a leader with Markfield around, particularly since he had Schottenstein's ear, one of the former executives, who worked in merchandising, said. It soon became clear to many that Markfield would not be retiring when he said he would, especially as Hanson tried to plan for the transition in the merchandising and design part of the company that Markfield oversaw. It was true that American Eagle's clothes and marketing needed to step it up — but if Hanson realized that, he was facing serious roadblocks in making those changes.

Two of the former executives interviewed for this story felt that Hanson wasn't a good fit for American Eagle, in part because he couldn't stand up to Markfield.

Hanson, too, could see what was coming. Despite having a year left on his contract, he had decided in January that he wasn't going to renew it, and had even been talking to other companies about a job once it expired, said two sources with knowledge of his thinking.

As it turns out, the old guard — led by Markfield and Schottenstein — beat him to the punch and made the hasty decision to fire Hanson before letting him finish out 2014, a decision that caught even Hanson by surprise, these people said.

It's not shocking the other six members of the board would allow such a decision; they too share some history. Two directors join Schottenstein as prominent Jewish leaders: Michael Jesselson is a trustee of Yeshiva University with Schottenstein while Noel Spiegel is a trustee of the Jewish Communal Fund. Another two are longtime associates: Janice Page has been on the board since 2004, and Thomas Ketteler has essentially been a director since 1994, though he was a paid adviser to the board between 2004 and 2010.

"People were basically in tears and in panic, it was so abrupt," the former merchandising executive said.

Wall Street was just as shocked as American Eagle employees. Only a week prior, Hanson had given a presentation at a major investor conference in Orlando, outlining his plans, over dinner with analysts, to turn around the business. Though American Eagle's performance last year was "no worse than anyone else," Hanson was spending a lot more money than many of his competitors, which might have spooked Schottenstein, said Nomura Securities analyst Simeon Siegel. Still, Siegel said he was "very surprised" when he heard the news.

Internally, five of the sources said morale has been low since Hanson's firing. "It was definitely deflating because Robert represented the hope of a new direction," said one employee. "I don't think the culture he cultivated will remain intact."

Markfield doesn't engender the same enthusiasm among the staff as Hanson did, these sources said, in part because while he can be charming when times are good, he can also be toxic and aggressive when times are bad. Recently, he has been flying buyers to New York to instruct them on how they should be selecting items, a move that's been viewed as slightly patronizing, and sitting down with merchandisers to explain what he wants to see in American Eagle's new clothing lines.

The renewed focus on product was a major point on American Eagle's earnings call last month, its first without Hanson. Schottenstein noted on the call that the new CEO must first understand operations and the balance sheet, "but at the same time has an understanding of merchandise itself. ... [and] has to have the proper respect of the merchandising team and be able to give the proper support to the merchandising team." The phrase "proper respect" was perhaps an allusion to the unpleasantness between Markfield and Hanson.

Markfield added: "Most people really don't know how to dress themselves, and really, what they're looking for is what they should look like, and what the outfit should look like. The stores will be hipper, and the markdown factor should be less."

But Rob Wilson, an analyst at Tiburon Research in San Francisco, wasn't impressed. "That was one of the worst conference calls I've listened to in my career," he said in an email to BuzzFeed. "Poor Hanson. Clear that he was just too intelligent for those Neanderthals running the show today."

Or, as the source inside the company said more diplomatically: "The main struggle within the whole brand is trying to figure out who we are, what do we sell, how do we approach fast fashion, how do we keep to our roots — it's just hard to stay relevant. I think that Robert had a better chance of capturing that maybe than the old guard, but the old guard, they feel they know what's up. They feel they can get it back on track."