American Apparel has been a nonstop source of controversy since its founding almost two decades ago, selling clothes and sex and battling a series of sexual harassment suits brought against Chief Executive Officer Dov Charney.

Now, the retailer has inspired the stage, in the form of a play written by Charney's cousin Oren Safdie. Unseamly, which premiered in Montreal last month, presents the story of an attractive Hispanic 20-year-old who's seeking legal advice for a sexual harassment suit against her former boss, Ira Slatsky, the controversial CEO and founder of an international clothing company called The Standard.

The Standard is described as a sweatshop-free apparel company, "famous for its sexualization of women" and provocative billboards, led by Slatsky, a hyper Jewish egomaniac in his early forties, according to the script, a copy of which was obtained by BuzzFeed.

The play paints an unflattering picture of all the characters, but especially Slatsky, who, like Charney, is also dark-haired and dresses in the kind of white short-sleeved polo favored by the real-life CEO.

Early on in the play, Slatsky tells Malina: "Do we sometimes push the boundaries of decency, dangle a little titty, twat and cock in their faces, try things that are a little 'controversial'? Of course we do! It's a hand-to-hand combat out there — everyone clawing for attention, trying to grab people's eyes from their sockets — and if we're going to survive against the A&F's, the F-c-u-k's, it ain't gonna be because of our high fucking morals. The ends justify our means — and you get that!"

An image of real-life Charney on the left. A photo from the play on the right.

"There's no getting away from the fact that people know he's my cousin," Safdie said in an interview. "All my plays touch on people I know in some ways. I personally in this play feel that all sides have given their voice."

Safdie says he's mostly a New York-based playwright but likes to try his plays out on other cities; eventually, it will be done in New York, he says. He has had several plays produced off Broadway.

Safdie says that he saw Charney a few months ago and that the CEO knew of the play. The two are first cousins — Safdie's father and Charney's mother are siblings. The feedback has been largely positive from audiences, according to the playwright.

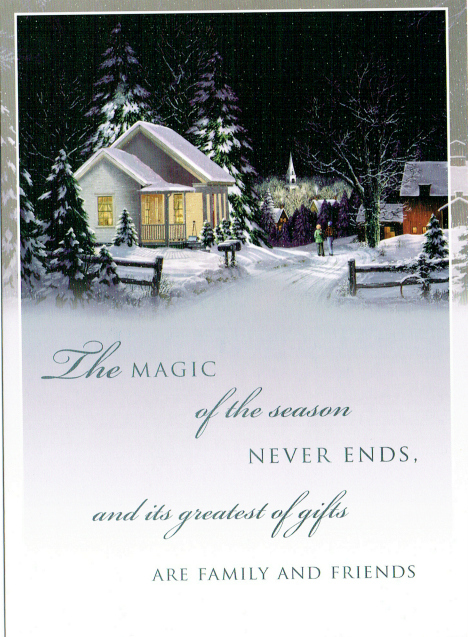

But it's not all positive: Safdie said he went to the Los Angeles police with a threatening greeting card that was sent to him recently with the message, "The magic of the season never ends, and its greatest of gifts are family and friends." The playwright's social security number was penciled on the inside and his credit card was subsequently flagged for fraud; the return address was that of a famous Canadian theater critic, who says he didn't send the letter. It also got the critic's home city wrong.

"Dov hasn't seen the play yet, but Oren's themes have often been influenced by the Safdie family, including his father and grandmother," Iris Alonzo, a spokeswoman for American Apparel, said in an e-mail today. "It's important to emphasize that his plays are works of fiction, loosely inspired by various events that the family has experienced over the years. Dov loves his cousin and is looking forward to seeing the play soon."

In the script, Malina, who starts working for The Standard when she's 17, is seduced by Slatsky, receiving perks like a promotion to store manager and a trip to New York Fashion Week while they're sleeping together. Once she's attached to him, he drops her, provoking a nervous breakdown, and she sees a lawyer to assess the probability of winning a sexual harassment suit against him in spite of agreements she signed with the company. (The story will ring bells for anyone that's followed American Apparel in recent years.)

At one point, the "off-kilter mid-level lawyer," as the character is described in the script, tells her it's "hardly a stretch of the imagination to make the case that you were, in effect, brainwashed" or a victim of Stockholm Syndrome. Malina's accusations are similar to those in a lawsuit brought against Charney by former employee Irene Morales. A judge dismissed that case in 2012 because a California court had already ordered the sexual harassment claim to arbitration.

The unsigned greeting card sent to the playwright:

The similarities between Slatsky and Charney are easy to spot throughout the play. At one point, the fictional Slatsky criticizes the media because "assholes don't recognize how we're revolutionizing the workforce," choosing instead to focus "on some little off-the-cuff remark I made about my CFO." That's a reference to when Charney called his CFO a "complete loser" to the Wall Street Journal, prompting the executive's resignation. The fictional CEO touts his business in the beginning of the play as "a sweatshop-free manufacturer, set up in this country, that offers its workers a living wage, access to healthcare, and free massages." That is exactly what American Apparel does. References are also made to the resignation of American Apparel's auditor in 2010, the company's plunging stock price and its immigration raid. The fictional CEO from the play, like Charney, doesn't hold a college degree and admits to relationships with employees.

While Safdie says there isn't any bad blood between he and Charney, the fictional CEO does make a disparaging reference to a cousin with an Ivy League degree in the play. (Safdie has a master's in fine arts and in architecture from Columbia University.)

"I'll tell you what you do see: a profile in the New Yorker," Slatsky rants to Malina. "Front-page features in the Times — both London and New York — and Los Angeles, not to mention spreads in Time, Newsweek, Vanity Fair, and I could go on and on — those are my bloody Ph.D.s. Nothing to do with Shakespeare or trigo-fucking-calca-lunguemus... I mean, what do you think that cousin of mine, with his Ivy League degree is doing now? Fucking living with his family in a studio rent-controlled shack — my uncle has to put him on the payroll just so he can get health insurance — so don't talk to me about college..."

Safdie notes the play "does not reflect" his relationship with Charney, and that the cousins were "quite close up until a few years ago," though they now see each other mostly during holidays and other family gatherings. He says that in American Apparel's early days, he and Charney went to Showtime and a couple of other networks to interest them in a TV series based loosely on the company. (They didn't bite.)

An excerpt of the play:

View this video on YouTube

He wrote the play two years ago but a couple of marketing tactics out of American Apparel since then made him wonder if he was giving the company ideas.

For example, in the play, the fictional CEO claims he plans to promote pubic hair on models next. The Standard also experiments with a nail polish colored named "Menstruation." American Apparel made waves this year for putting hair on the nether regions of mannequins, and drew headlines in the fall for a "Period Power" T-shirt.

"I was starting to think, 'Is this script being leaked somewhere?" he says.

Unseamly is meant to get people "to talk about the sexualization of our youth, and what the implications are down the road," Safdie said. "I brought up the billboards because it's not something you can turn off. When I drive my daughter to school and she sees a girl that looks probably 15, 16, in four different poses, I can't turn that off, it's not like television. We're all about freedom of this and freedom of that. I do believe the industry uses freedom of expression as a fig leaf to cover their asses for appealing to our lowest common denominator."

Asked whether he has shared his criticism of provocative billboards with Charney, who frequently relies on "freedom of expression" as a defense for racy pictures, Safdie says "he knows what my views are and what everyone's views are."

"I write my plays and don't worry about the consequences and he does his business and doesn't really think about what other people think and so that's sort of the way it is," he says. "I'm not going to lecture him, this play is not a lecture about that. It's putting it out there in my most objective way and allowing other people to come to their conclusions."

Safdie stressed that the play is not an attack on American Apparel.

"It's such a polarizing company, because it does so many good things, yet has these other things, so I guess the play is in a sense to put forward to people: What's important to you?" he explained. "Do you hold them accountable for these things on the right, even though they're doing these things on the left? All these elements make for really good drama."

Update — March 10, 2:50 p.m. ET: American Apparel notes that Safdie's plays are works of fiction that are loosely inspired by real events. "Dov loves his cousin and is looking forward to seeing the play soon," a spokeswoman says in an e-mail.