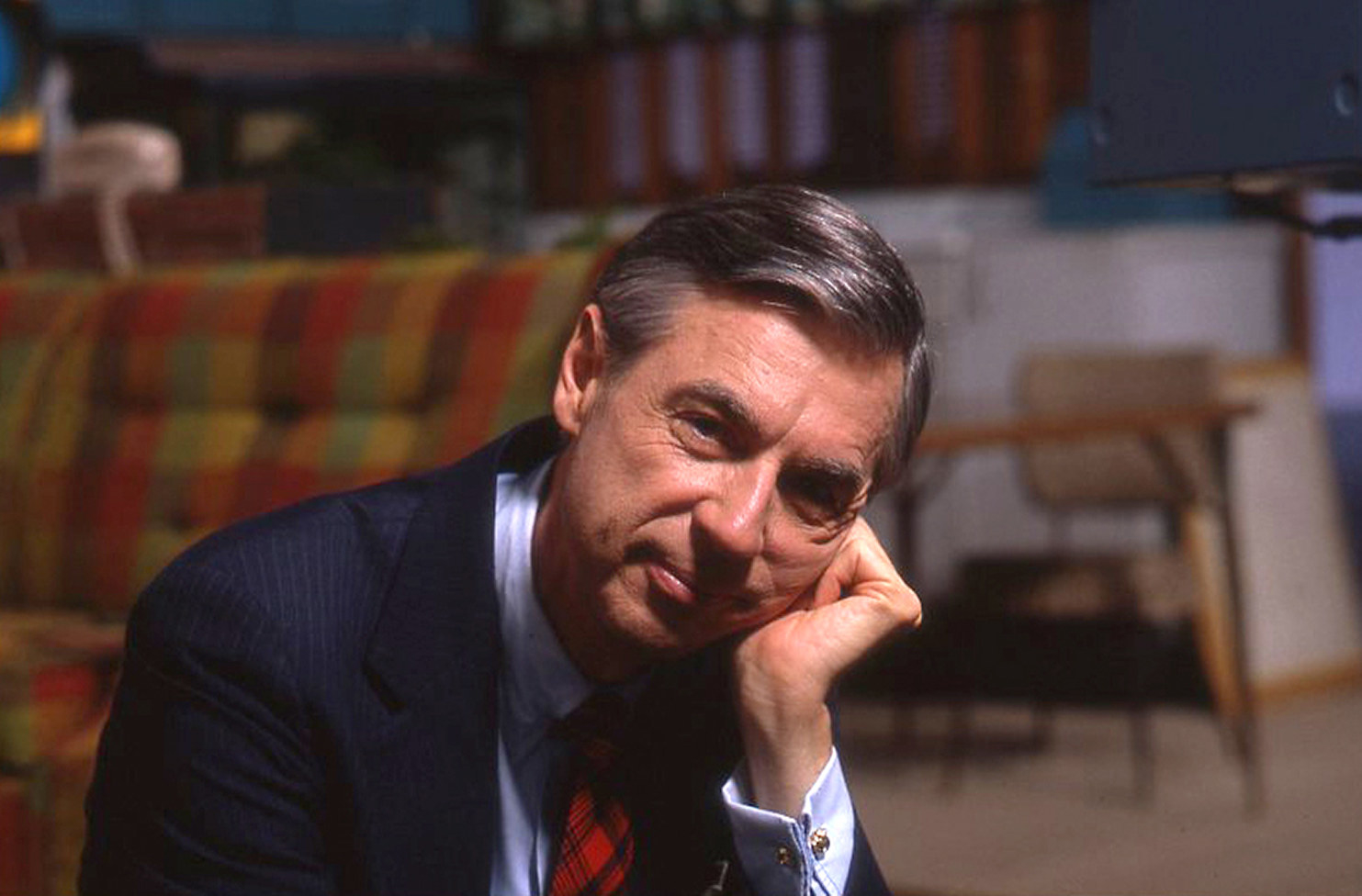

Like many others, I grew up watching Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. Parked in front of my family’s boxy Sony Trinitron TV, I devoured anything G-rated. But in the (then over 98% white) Maritimes of Canada, where my brother and I were often the only kids of color on the playground or in the classroom, Fred Rogers’ messages were especially comforting to my meek self. He assured me that I wasn’t a mistake (but it was normal to wonder if I was), that I was lovable, that I had inherent worth. I grew up without any of my own grandparents around, thanks to death or international distance, so that half hour spent together with Mister Rogers, every day, was part of a treasured routine through which he became my surrogate granddad. And I wasn’t the only one who felt this kinship; for decades, Fred Rogers was adopted as a father figure to millions.

It’s been 15 years since Rogers died, but his legacy has not just lingered — it seems to be resurging. In January, it was announced that Tom Hanks would play Rogers in the upcoming feature film You Are My Friend, while in March PBS aired an hour-long special on Rogers, It's You I Like, and the United States Postal Service dedicated a “Mister Rogers Forever” stamp, inspiring postal workers to share personal anecdotes on his influence and others to find excuses to send snail mail. And now, Morgan Neville’s Won’t You Be My Neighbor?, a feature-length documentary on Rogers and his lifework, is receiving a theatrical release. The trailer alone drew tears from me, along with many others.

Those of us who responded so strongly to the trailer, and since then to the documentary itself, have probably done so because Rogers has become a fond symbol of our childhoods, an embodiment of pureness and intention, and the selfless reassurance he provided as we grew up. But I wonder if it also partly stems from a current, collective pain and yearning for what he gave us. Even though we’re not kids anymore, we still need to hear that our lives have value, that perfection isn’t necessary, that we’re fine as we are — perhaps now more than ever.

Rogers also encouraged us to take the time to care for ourselves. Long before self-care became a buzzword, the spirit of it infused Rogers’ show, down to the unintentional ASMR of his gentle, languid diction. Now that the 24/7 news cycle ensures that school shootings, natural disasters, and terrorist attacks are constantly spilling across timelines and tickers, Rogers’ particular brand of self-care seems more critical than ever.

Our modern conception of self-care basically uses simple airplane safety logic: You need to put your oxygen mask on first before you can best help others. And Rogers’ own school of self-care and self-love — using tools like ritual, making mindful time for yourself and your emotions, affirmation and encouragement, and a disregard for perfectionism — embraced that philosophy. An ordained and spiritually open-minded Presbyterian minister, he wanted you to “love thy neighbor as thyself,” but realized how crucial and difficult the latter part can be.

We live in a culture obsessed with self-improvement and becoming more, accumulating bigger and better things. And buried in that is an implication that we aren’t enough. So it’s not surprising that Rogers and his message of unconditional self-acceptance still feel like a balm to so many of the kids who grew up to be adults in this world.

Each episode of Mister Rogers begins the same way: The twinkling notes of a celesta play while the camera pans over a miniature town; a close-up of a traffic light flashing yellow — a cue to slow down — just before Rogers arrives home, singing that “it’s a beautiful day in the neighborhood.” He swaps his jacket for one of his trademark cardigans — knitted by his mother until she died — and his dress shoes for blue canvas sneakers. Watching the show became my own routine as a child, and the consistency of those ritualistic actions was a pseudo-Pavlovian signal that it was time to relax and play, that this time had been set aside for me. It was a welcome respite from the chaos and constant change built into childhood, and today feels almost otherworldly — and necessary — considering how overstimulated most of us are, juggling smartphones and laptops while watching TV, toggling between two gears: sleep and go-go-go.

Rogers’ other rituals bled into my young life in concrete ways. One day, my parents bought me eight goldfish because Rogers had an aquarium on his show. I fed them every day, my tiny hands shaking a plastic bottle of fish flakes over the tank of water with care. My nose sometimes scrunched at the smell, but involuntarily so — I enjoyed the act and took quiet pride in it. My mom says we got the fish so I could learn how to love and care for other creatures, and it seemed to work.

But where Rogers really influenced me was in forging a relationship with myself. In addition to a tendency to be hyperkinetic, children’s TV programming often (still) focuses on social interactions and goals. It tells kids how they should function and deal with others (e.g., sharing, politeness, chores). It’s future-oriented. Rogers covered these topics in oblique ways, leading by example instead of formally teaching or preaching, and focused more on feelings, how kids should accept and deal with themselves in the present. “I feel that if we in public television can only make it clear that feelings are mentionable and manageable, we will have done a great service for mental health,” says Rogers in his David and Goliath–esque (and ultimately successful) plea to the US Senate for public television funding in 1969. His goal was to help children learn how to sit in their emotions — being instead of becoming.

Rogers was impressive in his ability to make each individual viewer feel special. We each felt like he was ours, and he wanted us to feel that way. He’d look straight down the barrel of the camera, talking to you. “When I look at the camera, I think of one person. Not any specific person, but one person. It’s very, very personal,” Rogers says in Neville’s documentary. He considered the space between the screen and viewer “holy ground” and chose to have children on the program sparingly, to avoid viewers feeling jealous or competition for his attention. As a child, this kind of undivided focus made me feel valued and, in turn, helped me value myself.

My family moved a lot when I was growing up — I bounced between four different elementary schools — and I was an uncommonly quiet kid who never made many friends at any of them. My recess breaks were often spent sitting on a bench, reading or drawing, while classmates ran around the courtyard, playing with one another. But at the time, I felt fine, content, well-rooted. And I really do believe my young self-assuredness stemmed at least in part from being reminded, again and again, that I was both unique and loved.

Every day that I watched Mister Rogers, he would sign off with the same words: “You’ve made this day a special day, by just your being you. There’s no person in the whole world like you, and I like you just the way you are.” In the lexicon of self-care, affirmations are private — messages from yourself, to yourself. But Rogers’ farewell provided a template, words to revisit in moments of reflection. And like any affirmation, their positive effects through daily repetition were cumulative. Rogers was said to consider his show “tending soil,” and it helped me eventually blossom into someone still shy, but more cordial — and always still me.

Rogers’ positive influence reaches beyond his target demographic, and I still turn to him for consolation or assurance as an adult. And while I admit there’s comfort in his familiarity, it’s more than that. (Otherwise I’d be equally soothed by reruns of Romper Room.) For one, Rogers was happy to take his time — it’s mentioned in the film how he once sat in silence with an egg timer to show how long a minute is — and focus on the task or moment at hand. He valued airtime in a way that remains wholly unconventional, particularly in kids programming; he understood that the jamming of “content” or activity into every opportune moment wasn’t necessarily making the most of that opportunity. And as more adults and businesses see the value in mindfulness over multitasking, it seems Rogers had long been onto something as he encouraged viewers to calm down, be present, and take care of themselves.

If I’m feeling particularly sad, inadequate, or anxious, I’ll rewatch clips from old appearances or episodes, like Rogers serenading the camera with one of his best-known songs, “It’s You I Like. (In Won’t You Be My Neighbor?, he sings this in a duet with Jeff Erlanger, a smart and plucky boy with quadriplegia.) The message is so simple — It’s you I like / Every part of you / Your skin, your eyes, your feelings / Whether old or new — but somehow cuts through whatever’s weighing me down. For some, a self-care practice might mean hiking scenic trails, taking a bath, or unplugging their devices; for me, it’s watching old, lo-fi videos of Mister Rogers.

After going through a particularly tough time two years ago, I bought a daily calendar last year offering his words of wisdom. On many days, those words didn’t apply to me — they were about parenting or dealing with children — but on other days, it almost felt as if the messages were speaking directly to me, the way Rogers himself used to. Underemployed, alone in a new city and country, and seemingly blowing through money just by breathing, I flipped my calendar on Sept. 19 (I saved the page) to the printed lyrics of a Rogers song: “It’s not easy to keep trying, but it’s one good way to grow.” Mister Rogers had always said to look for the helpers in trying times, and when I was at my lowest, I always found myself searching for him.

Neville (who also directed the Oscar-winning 20 Feet From Stardom) says he made Won’t You Be My Neighbor? because the voice of Rogers has disappeared. “It’s a voice I don’t hear in our culture anymore. It’s a voice of an empathetic adult who’s not condescending, who is trusting — it’s all of these things I find empty from our media culture, empty from our political culture.”

But it’s worth remembering, even when he was still alive, Rogers’ voice was slowly being drowned out. In a poignant 1998 Esquire profile, journalist Tom Junod wrote, “Mister Rogers is losing, as we all are losing. He is losing to it, to our twenty-four-hour-a-day pie fight, to the dizzying cut and the disorienting edit, to the message of fragmentation, to the flicker and pulse and shudder and strobe, to the constant, hivey drone of the electroculture…and yet still he fights, deathly afraid that the medium he chose is consuming the very things he tried to protect: childhood and silence.”

Considering the flak and criticism Rogers (of all people) faced when he was alive — his sexuality was called into question due to his mild demeanor, while Fox News announced he was an “evil, evil man” who encouraged kids to be self-important and lazy — it bears wondering if his message would survive now. Could someone like him be accepted, much less given a national platform, in our increasingly noisy, cynical, and bleak world?

In all its warmth, Won’t You Be My Neighbor? proves how deafening Rogers’ absence is. When I think about how much of an imprint he left on me, how often I still come back to him in times of emotional need, I wish he were still here to help comfort today’s kids. So many are being told directly and indirectly that their needs don’t matter — immigrant children separated from their parents and abused, young people in conflict zones, the rising number of kids with severe anxiety — and Rogers would’ve reminded them that they’re indeed special, lovable, and capable of loving. He’d help them sit in painful feelings and find productive ways of expressing them. And he’d let them know they are worthy of respect, care, and attention.

It feels risky to love any public figure fiercely these days, especially one from our childhood. Bill Cosby and his criminal offenses, for example, have sullied what were fond memories of The Cosby Show and its star. And if actors don’t morally fail us, their activities offscreen can still taint our memories (case in point: Barney). So what may be most comforting to realize is that Fred Rogers was both what he seemed and — as this film shows — more. Won’t You Be My Neighbor? reminds us how radical and singular Rogers was, but also how much he simply wanted us to be kind to each other and ourselves. And despite his absence, that’s something we can still strive toward. ●