It’s been nearly 25 years since Diana Spencer, Princess of Wales, died after a disastrous car chase in Paris. She had already been a global icon, but her tragic death somehow amplified her eminence. It was only after Diana’s death, when then–UK prime minister Tony Blair was giving a grief-stricken speech, that he first dubbed her as “the people’s princess” — a term that resonated and has since endured.

And now, it seems like she's everywhere. In July, on what would have been her 60th birthday, a memorial statue of the late royal was unveiled at Kensington Palace, surrounded by forget-me-nots — Diana’s favorite flower. CNN recently added to the reservoir of Diana documentaries with an original six-part series while director Ed Perkins is working on his own archival theatrical documentary to be released next year. And last year, Emma Corrin delivered a Golden Globe–winning performance as the princess in Netflix’s The Crown while Elizabeth Debicki will take over the potentially controversial role in the upcoming final two seasons.

She’s not treated as a real person in these varied mediums, but more as an abstract concept: a victim and martyr — an idol we can project onto.

Diana has been fictionalized onscreen before. In 2013, Naomi Watts starred in Diana, a biopic depicting the final two years of the princess's life, including her romance with Hasnat Khan, a heart surgeon. (Watts would later describe the critically panned film as a “sinking ship.”) And now, two more projects — very different in their approach — are populating screens: a filmed version of Diana: The Musical, starring Jeanna de Waal, and Pablo Larraín’s Spencer, starring Kristen Stewart. It’s official: We’re in a Dianaissance.

This might be partly fueled by The Crown’s popularity as well as persistent headline news involving Meghan Markle and Prince Harry, who left royal life last year. Comparisons between Meghan and Diana have become common thanks to their shared experience being at odds with the monarchy’s rigid, institutional expectations, as well as each woman’s cruel and invasive treatment by the media.

Part of the reason Diana’s death was so unforgettable is that it was presented to the public on a then-unprecedented scale. Compared to the death of major figures preceding her (e.g., JFK), the fresh existence of a 24-hour news cycle intensified the tragedy’s mileage. The accident — and speculation surrounding it — was covered continuously, and so were aftereffects. Meanwhile, an ongoing, worldwide vigil seemed to take place.

Diana also happened to die just as the internet was beginning to become widespread — yet another tool contributing to her cult hero status, most recently thanks to social media. Gen Z’ers are using Diana’s canonization as a subversive way to mock boomers on Facebook. A clip of Corrin as a bashful Diana with evasive eyes has become a meme. And Taylor Swift’s recent fashion styling drew quick comparisons to the late princess’s proverbial revenge dress.

But the production of recent works like Diana: The Musical and Spencer prove Diana isn’t merely a tool for cultural reference; she is being ossified into a myth. The repeated exhumation of her story demonstrates the superficial ways in which both artists and the media seek to define and use her, rather than provide real insight into her life. She’s not treated as a real person in these varied mediums, but more as an abstract concept: a victim and martyr — an idol we can project onto. In 1997, when examining why she and her friends were so deeply affected by Diana’s sudden death, writer Francine du Plessix Gray cited the princess’s relatability: her experience as a lonely but married woman, the still-stinging disappointments and betrayals from men, the way she seemed discarded once her perceived duties were done. “All too many women have suffered some modest, plebeian measure of her heartbreaks,” Gray wrote in the New Yorker.

Diana’s death could have been epochal in terms of how public figures are portrayed — especially considering how her death occurred. Instead, we keep resurrecting Diana for our entertainment, spinning new versions of her story and emphasizing its most traumatic parts, all without any self-reflection. With each new iteration of a Diana narrative, we only seem to wade further into fictitious folklore, distancing ourselves from the truth and complexity of who she was, what made her special, and what we could serve to learn from both her life and death.

Six weeks before its Broadway opening on Nov. 17, Diana: The Musical, directed by Tony-winner Christopher Ashley (Come From Away), debuted on Netflix. The filmed production — which purportedly tells “the story you only thought you knew” — has been panned by the general public and critics alike (The Guardian gave it a 1-star review). In its defense, it’s not all bad. The cast is talented and committed, doing what they can with the material. The show executes impressive quick changes and the re-creations of Diana’s wardrobe are fantastic (even if Diana herself thought too much emphasis was put on her clothes and famously auctioned off 79 dresses for charity). The musical’s depiction of Charles and Camilla as erstwhile star-crossed lovers is refreshingly empathetic, and Diana also acknowledges how media savvy and tactical the princess became — a fact that often goes glossed over in dramatizations of her life.

The production might’ve gelled more if it were pointedly satirical or campy, but it has too much earnestness — not to mention a weird, false sense of profundity.

Otherwise, however, the production is a mess. Blending structural and thematic elements seemingly inspired by Evita, Bombshell — the fictional Marilyn Monroe musical from NBC’s Smash — and even Hamilton, most of it doesn’t land. The depthless show is full of ineffective leitmotifs, too-abrupt tonal shifts, and ludicrous lyrics; at one point, Diana stops singing in Spanish(?!) to woefully croon how she "should’ve known better than to marry a Scorpio.” The production might’ve gelled more if it were pointedly satirical or campy, but it has too much earnestness — not to mention a weird, false sense of profundity.

Diana comes across as a clueless normie as Charles courts her — the beginnings of a fairy tale — when she actually came from an aristocratic family. In the much-mocked “This Is How Your People Dance," she’s bored by classical music whereas in real life the princess loved both modern and classical music, training in ballet and as a proficient pianist (who could play Rachmaninoff by heart). Then there’s “The Main Event” where Diana confronts Camilla — something that actually happened, but whereas the real Diana claimed her approach was sympathetic yet firm, the musical presents the scene as a full-on fight (the chorus sings that it’s the “Thrilla in Manila, but with Diana and Camilla!”).

These inaccuracies show how Diana has become (or perhaps on some level has always been) an empty canvas — a vehicle for whatever message a storyteller might choose, and frequently in a way that lines their pockets. In an opening night interview with Variety, producer Frank Marshall said, “Look, this is one way of telling her story, and we have to face reality that it was a tabloid story.”

Waal, who plays Diana, was equally defensive. “I’m intrigued why people think it’s great to make a really serious film about her,” she told Variety, referring to Spencer. “But really bad to make a light-hearted musical. They’re both produced privately for profit, and they’re both entertainment. So, why is one fine and the other isn’t?”

While Diana: The Musical attempts to cover 15 years of the late princess’s life, Pablo Larrain’s Spencer takes place over three days, beginning Christmas Eve of 1991. That was the last Christmas before Charles and Diana officially separated (they’d finally divorce in August 1996), and here in Spencer, disaffection between them has reached an all-time high. Diana’s at the edge of a precipice, experiencing bulimia and self-harming.

Diana wrestles with isolation, paranoia, and expectations placed upon her in the name of tradition (which no one is above, she’s told). She must spend the holiday at the cold and eerie Sandringham House (whose estate happens to include her now-decrepit childhood home). She’s told what to wear and when. Upon her arrival, she’s asked to weigh herself — a practice to encourage indulgence over the holiday. “All the things in the film that seem least believable are true,” the film’s writer, Steven Knight, told the Telegraph last month. But Knight was presumably referring only to royal customs as Spencer actually leans heavily on flights of (often macabre) fantasy. At one point, Diana gulps down a pearl necklace. Throughout the film, she sees the ghost of Anne Boleyn, Henry VIII’s ill-fated wife. (“Go! Run!” Boleyn urges.)

Indeed, with the help of masterful cinematography by Claire Mathon and a chillingly chaotic score by Radiohead’s Jonny Greenwood, Spencer inhabits the dramatized world of an art house, psychological thriller — reviews have compared it to The Shining — rather than a factual biopic. Surrealist, absurdist, and (arguably too) heavy on metaphor, the film deflects obligation to historical accuracy. A disclaimer appears at its onset (one much like Netflix has been asked, and refused, to incorporate for The Crown): “A fable from a true tragedy.”

Placing Spencer over a short timespan is a bold choice and a smart move narratively (particularly considering the musical’s unwieldy breadth): Her emotional turbulence feels intensified amid the staid and condensed setting. Then again, the short timeline forces scenarios that aren’t as clearly fictive as eerie apparitions (e.g., Diana had reportedly stopped self-harming at this point in her life and, according to Rolling Stone, was on the road to recovery from bulimia by the late ’80s). Perhaps this best points to what feels off about the Diana renaissance we seem to find ourselves in: Her life and story are being oversimplified, predominantly living in her trauma. Though the princess once suggested it was her strength that caused friction within the palace walls, Spencer feels like a fantasy film centralized on Diana’s victimhood.

Spencer may be touted as a survivor story as Diana eventually leaves Sandringham with her sons in tow, eschewing royal life for her happiness. But though her marriage was unhappy, Diana did not really want a divorce — the Queen ordered it, with Charles’s support. Also, Diana never rejected the monarchy as an institution either; after all, she was mother to the future king and had descended from nobility herself. Spencer miscalculates how empowering this ending feels, particularly when it’s at the expense of Diana’s complexity.

The film delves into many harrowing aspects of Diana’s life, but in doing so, it flattens her. While Spencer doesn’t vilify Diana for her mental health struggles and self-injury (nor does Diana: The Musical, for what it’s worth), it overemphasizes them. The film contributes to a framing that Diana often fought against in order to be taken seriously — that she was temperamental and emotionally unhinged. Spencer also seems to attribute her struggles to the stifling system of the monarchy. But, while partially true, that explanation is too tidy and convenient.

The truth is many factors contributed to Diana’s ills and insecurities. According to Andrew Morton’s Diana: Her True Story (which the princess was secretly a source for), she felt inadequate throughout her schooling and childhood, growing up with an absent mother. And while her eating disorder was exacerbated by a troubled marriage and palace life, it likely originated through her unhappy upbringing as well as her being an impressionable younger sister. Though Diana had once said her bulimia began due to an insensitive remark from Charles, she revealed in 1997 — when speaking privately to patients at an addiction clinic — that her disorder preceded her royal life: “It started because [my sister] Sarah was anorexic and I idolized her so much I wanted to be like her.”

Her life and story are being oversimplified, predominantly living in her trauma.

To invent a three-day scenario and throw in all of her trauma — particularly during a period where she may have overcome a large deal of it — ignores her evolution. Diana was a kaleidoscopic person, undergoing numerous changes and phases; it’s reductive to treat something she expressed at one period as perpetual or definitive. For example, she regretted ever calling herself stupid — in an effort to put a child at ease — because that label followed her (and is stressed ad nauseam in Diana: The Musical). “I don't think I've been given any credit for growth,” Diana expressed to the BBC in 1995. “And, my goodness, I've had to grow.”

“They’ve piled every bad thing into one weekend which is taking poetic licence a little far,” writer Ingrid Seward said to the Telegraph. Seward, who knew and had interviewed Diana shortly before her death, doesn’t believe the princess saw herself as a victim: “She saw herself as a single woman before the end of her marriage. She was very funny about it all, that’s how she dealt with life — she was either crying or laughing.”

It’s true: The real Diana — whose trademark warmth is mostly missing in Spencer and other dramatizations — was known to be disarmingly charming and funny, according to her loved ones and various acquaintances. The princess even once joked publicly about the speculation on her bulimia and mental state. “Ladies and gentlemen, I think you’re very fortunate to have your patron here today; I’m supposed to have my head down the loo for most of the day. I’m supposed to be dragged off in a minute by men in white coats,” she said in a 1993 speech. “So if it’s all right with you, I thought I might postpone my nervous breakdown to a more appropriate moment.”

Cultural revisionism has been all the rage lately, as has our desire for collective atonement. Society has changed its tune on once-maligned women such as Monica Lewinsky and Britney Spears, and the media seems to be a big part of that switch. (Though things have turned pretty exploitative with Spears, who’s been the uninvolved subject of five documentaries within a year.) Meanwhile, notable history podcasts such as You’re Wrong About and Not Past It are adding to this popular “For Your Reconsideration” type of dialogue. But Diana seems like an odd figure to incorporate into this wave. Her story has long been well-documented and, unlike Spears and Lewinsky, she was not deeply disparaged by the general public.

The stories we tell about Diana say more about us than they do of her.

Though Larrain’s respect for his subjects is evident, it’s alarming how eager audiences are to consume narratives of vulnerable, alienated, suffering women. According to journalists who knew Diana personally, not only would Diana “be horrified” at this slanted portrayal of her, but it also won’t sit well with her sons William and Harry, who have often criticized how the media has exploited and commercialized their mother.

In the first episode of The Me You Can’t See, a mental health documentary series produced by Prince Harry and Oprah Winfrey, the prince talks about experiencing his mother’s death as a 12-year-old while having to deal with the public’s grief. “It was like I was outside of my body and just walking along, doing what was expected of me. Showing one-tenth of the emotion that everybody else was showing. I thought, This is my mum. You never even met her.” Oprah then suggests that those who admired Diana from afar were able to process her death more than Harry could, and he agrees: “Without question.” The young princes’ ability to mourn Diana was stunted by the public’s feelings of ownership of her when she died, and yet that entitlement only feels ongoing.

Regardless of how the princess used the media herself, the press caused her much grief. “Very sadly, a lot of my memories revolve around trying to cheer her up,” said Prince William in Diana, 7 Days — a 2017 documentary that he and his brother commissioned. “And I believe that she cried more to do with press intrusion than anything else in her life.”

Just earlier this year, revelations concerning Diana’s infamous BBC interview with Martin Bashir arose; Bashir had falsified documents to suggest the princess was being spied on, using her ensuing paranoia to book the interview. Prince William has blamed the interview for worsening his parents’ relationship (the Queen ordered they divorce after its airing) and his mother’s mental health. “The BBC’s failures contributed significantly to her fear, paranoia, and isolation that I remember from those final years with her,” the prince said in May. In his own statement, Prince Harry said that “the ripple effect of a culture of exploitation and unethical practices ultimately took her life.”

A dominant theme in these films is how the royal institution is a prison. But the same can be said about public image in general. And despite our reckoning with the role that public obsession played in her death, this new spate of narratives still harps on that same need: knowing more about the princess than we are entitled to. And in a perverse way, by engaging with these recent Diana narratives — giving them our money and attention and thus perpetuating her name’s bankability — we seem to be dismissing any culpability we collectively had in her demise. The stories we tell about Diana say more about us than they do of her.

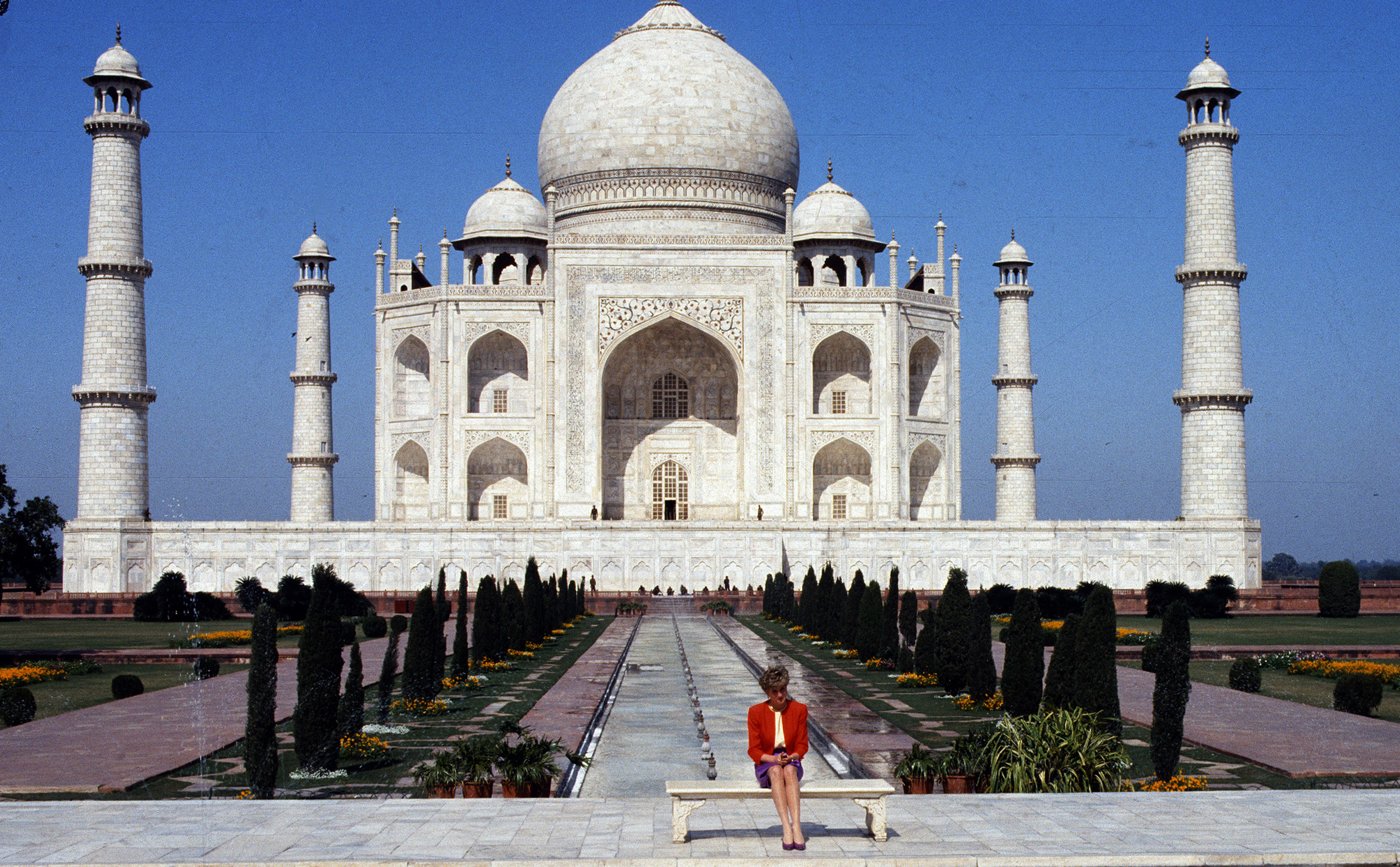

Even though she was called the most photographed woman in the world, there’s one image of Diana that remains especially iconic. She sits on a marble bench in front of the Taj Mahal in a poppy-red blazer and an amethyst-hued pencil skirt with matching pumps. Her head is tilted demurely as she holds sunglasses in her lap, her legs in the trademark duchess slant. Her 5’10” frame looks small against the majestic backdrop of the world-renowned monument. She is alone, her husband notably absent. Papers ran wild with the image, saying it signaled the end of her marriage. The story is that it painted a “picture of loneliness.”

What the public didn’t see, however, were the 30 to 40 photographers clamoring for that specific photo, goading her to sit down, insisting that only she be in the frame (you can even hear them yell). They wanted her isolated. It was actually known for weeks that Diana would be at the famed mausoleum solo while Charles had commitments at a forum in Bangalore. With the scene set, the media knew what they wanted — a vision of love gone wrong. And thanks to an obliging Diana, they got it.

But there was another, lesser-known photo from that day, taken a few hours earlier at the Agra Fort. Only one photographer had bothered showing up for that tour stop. The Taj Mahal is behind Diana, this time far away and out of focus. The princess grins, her chin up and eyes mirthful. She’s alone and seemingly in the middle of a laugh. The snapshot tells a different story — obviously not a comprehensive one — but one that, despite the myriad of Diana projects that keep being made, seems to go untold. ●

Sandi Rankaduwa is a Sri Lankan Canadian writer and filmmaker. She was chosen as a Hot Docs "Doc Accelerator" Fellow in 2020, and her most recent film — a short documentary called Ice Breakers — was produced by the National Film Board and named a Vimeo Staff Pick. Her cultural criticism has appeared in the Believer, Rolling Stone, and BuzzFeed, and she was named a BuzzFeed Emerging Writer Fellow for 2018.