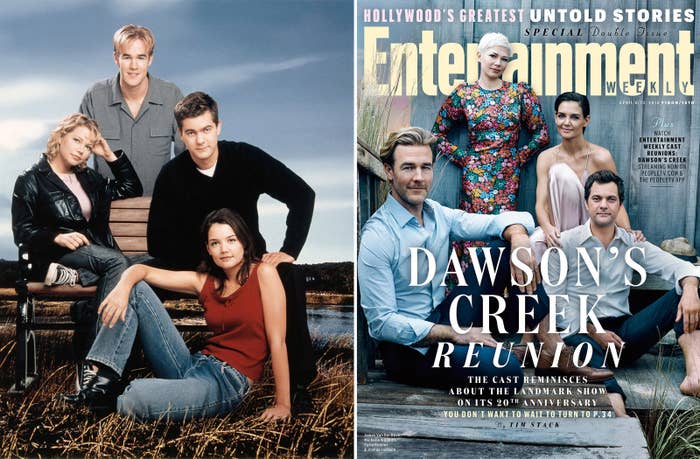

When Entertainment Weekly released photos from a Dawson’s Creek cast reunion at the end of March, people took to Twitter to air their many hysterical feelings. Fans tweeted the viral GIF that keeps on giving, Crying Dawson, and joked about canceling meetings or leaving the world altogether (“My cause of death: @EW Dawson’s Creek Reunion Issue”). It was the first time the entire main cast had been seen together since the show’s finale, which aired 15 years ago. Hulu traffic for the show quadrupled the weekend following the EW cover, with some fans clocking in 94 hours of binge-watching to consume the entire series — 128 episodes — within a week.

Such stats shouldn’t be surprising. Airing in over 50 countries, the show about tormented teens growing up in Capeside, a fictitious coastal town, was a paragon of adolescent programming for an entire generation of international viewers. Twenty years after its premiere on the WB, the then-fledgling, thereafter-flourishing, and now-defunct network predecessor to the CW, the uncommonly earnest teen drama still influences contemporary pop culture. In a video for GQ, Michael B. Jordan indulged a woman’s fantasy by lounging on a couch: “Wasn’t it always supposed to be Pacey?” he asks the camera. Last year, indie hit Lady Bird used Capeside couture — preppy basics like cargo pants, tank tops, and baggy sweaters — as inspiration for its wardrobe while rapper Ty Dolla $ign dropped a track titled “Dawsin’s Breek.” And three weeks ago, when asked if she’d been a big Creek fan growing up, comedian Amy Schumer replied, “Yes, of course. I have a beating heart.”

Dawson’s Creek premiered on Jan. 20, 1998, to 6.8 million viewers and, within two months, was the highest-ranked show on the WB. Admittedly, this alone says little; its overall Nielsen numbers didn’t compare with major networks airing more adult-geared fare like Friends or ER. Yet Dawson’s Creek was deemed a staggering success because it hooked an overlooked but coveted audience: teen girls. The premiere alone saw a 41 share in the female teen demographic (i.e., nearly half the teens watching TV in the country had tuned in), and the next week, ratings actually increased. Airing a month after the blockbuster movie Titanic, the show tapped into the same audience who kept the ill-fated ship afloat: “Titanic’s popularity kept it in the multiplexes for months after its release. But it was still just one movie. The WB had the same crowd flocking to the network every week,” write Susanne Daniels and Cynthia Littleton in Season Finale: The Unexpected Rise and Fall of the WB and UPN.

Thanks to this traction, ad revenue for the WB soared (from $100 million in 1996 to well over half a billion dollars in 1999), soundtracks sold and charted, and the show became a space for ample product placement, too. According to Billion-Dollar Kiss, a book by Dawson’s Creek staff writer Jeffrey Stepakoff, characters wore clothes from J.Crew and, later, American Eagle while driving vehicles provided by Ford for promotional purposes. Product placement in TV wasn’t new, but the series was significant in its ability to merge with merchandise seamlessly; it never felt glossy or commercialized, and teen viewers didn’t feel swindled into spending money. Sure, perceptive viewers may have noticed Urban Decay lipsticks, peasant tops straight out of dELiA*s catalogs, and Jane or YM magazines (RIP), and there was that one episode where Dawson (James Van Der Beek) and his dad (John Wesley Shipp) debated Macs versus PCs, but the series always valued sincerity over consumerism. After all, the most memorable purchase made in Capeside wasn’t sold at a nearby retailer. It was a wall.

So what exactly made the show such a blockbuster with teens? And why, 20 years later, are people still so emotionally attached to it?

The late ’90s and early aughts marked a particularly precarious time to be young in the US. The Columbine High School massacre — in which two students, Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, killed 12 other students, a teacher, and then themselves — occurred 15 months after Dawson’s Creek premiered and seemed to trigger a movement of school shootings that continues today. (By sheer coincidence, the two episodes of Dawson’s Creek immediately following Columbine dealt in part with bullying and the shocking death of Capeside High student and shit-stirrer Abby Morgan.)

Columbine was a sobering, watershed moment for American teens, turning formerly safe spaces into potential danger zones. And then two years later — as the teens on Dawson’s Creek prepped for their college years — Sept. 11 happened. At a time in teens’ lives when they’re tasked with trying to understand their place in the world, events unfolding around them were becoming increasingly senseless. So it’s not entirely surprising that a show featuring confused, outsider teens who seemed more self-aware than the adults around them became comfort food for so many young Americans. Schools and public spaces weren’t safe anymore, but a fictional small town that still felt wholesome could be.

Dawson’s Creek has always been a show steeped in nostalgia, and it’s important to recognize how nostalgia is generally comforting, but also fallacious — it tinges memories into something sunnier than reality. But despite its nostalgic elements, Dawson’s Creek managed to portray a warts-and-all world in which viewers watched smart, stubborn, and emotional characters search for stability, and seeing them both struggle and succeed in a controlled space became therapeutic. The breadth of characters was wide enough to give everyone at least one person to root for and relate to, especially for a primarily teen girl audience.

On Christmas Day, 1998, Entertainment Weekly printed an article on the “women of WB” with an iconic photo spread. In it, the leading ladies of Dawson’s Creek, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Felicity, Charmed, and 7th Heaven appear solemnly in an autumnal forestscape wearing corseted gowns in pale tones of pink and amber. The ethereal image suggested both their powers of enchantment and, with its fallen leaves, the changing of seasons. And despite the mythic imagery, it rang true: Young women were the driving force in the success of both the WB and Dawson’s Creek, whether watching the screen or appearing on it, and thus changed the landscape of television.

In the show’s pilot, women are problems to be solved: Joey (Katie Holmes) challenges hero Dawson by insisting they must grow up. Jen (Michelle Williams), a cool and sexy ex–New Yorker moves to Capeside, becomes Dawson’s new romantic conquest and Joey’s competition for his affection. Pacey (Joshua Jackson) lusts for his teacher (an ill-advised trope likely inspired by the Mary Kay Letourneau controversy at the time). And matriarchs pose as problems too: Grams (Jen’s pious grandmother played by Broadway veteran Mary Beth Peil) is overbearing, and Dawson’s mom, Gail (Mary-Margaret Humes), is revealed to be having an affair.

But as the show moved along, so did the spotlight. The boys remained important, challenging ideals of masculinity that hinge on emotionlessness and invulnerability: Dawson and both his daydreaming and disillusionment were still a mainstay, Jack’s (Kerr Smith) journey as a gay teen made TV history and brought comfort to queer and questioning kids, and dark horse Pacey became America’s favorite boyfriend. But Joey Potter, the tomboyish underdog who lost her mother to cancer and her father to jail, became the show’s anchor and the only character to appear in all 128 episodes. (In his book, Stepakoff writes that when Greg Berlanti geniusly suggested the pivotal kiss between Joey and Pacey in the third season, the show’s franchise was finally discovered, namely “kissing Katie Holmes.”)

Even though the show’s initial depictions of its female characters were prosaic, teen girls cherished the odds-beating and defiance eventually exhibited by all of the show’s women, and felt lifted up by them. It gave them something to cling and aspire to. An anonymous poster on the internet forum Data Lounge wrote, “Joey was always the character to whom I most related. She was the homely girl. It was so fitting that she sang "On My Own," as she was clearly Eponine, even down to her shitty family. I was so happy when she got with Pacey and found a little bit of happiness.” In a post on celebrity gossip blog Oh No They Didn’t that counted down the show’s most gut-wrenching episodes, user champagnexdream said, “Watching now Joey annoys me much more but I related to her SO much as a teen and tbh her character partly inspired me to become a writer!” And writer Ashley C. Ford recently tweeted about having felt a kinship with Joey as a young girl whose father was also incarcerated.

While Joey was on a pedestal and often the show’s (sometimes annoying) moral compass, she constantly dealt with classism and family issues. Meanwhile, the show portrayed complex, flawed, and persevering women in its other female characters, too. Gail struggled with the erasure forced upon an aging woman. Type A overachiever Andie (Meredith Monroe) arrived in the second season and grappled with mental illness. And then, of course, there was Jen Lindley. Despite her initial plot-driving purpose as a wedge between Dawson and Joey, Jen routinely spoke out against roles relegated to women. In the third season, Joey laments how she doesn't want to be the typical villainous girl of lore, the "wicked, conniving whore who manipulates her way between two brothers or two best friends.” Jen’s incisive response? "Joey, keep in mind that most of those stories have been written by men."

Despite her sagelike qualities, Jen was admittedly more despised than loved, particularly during earlier seasons. (Michelle Williams, the youngest in the cast, recently recalled the existence of an “IHateJen.com” website and said the hate was a struggle to deal with at the time.) But she ultimately provided a sympathetic look at wounded, rebellious girls and helped subvert the Madonna-whore complex that the series sometimes fell into perpetuating. As fans grew up and rewatched the series, some began to appreciate Jen — who broke convention but never seemed to catch a break — a lot more.

If there’s one resounding, resilient criticism of Dawson’s Creek, it’s in the verboseness of its teen characters. But its young actors appreciated the lines they were given. “I enjoyed the fact that, you know, being a kid at that time, playing a kid who wasn’t an idiot or the precocious one. [Kevin Williamson] never insulted the audience by dumbing us down to be believable teenagers,” said Joshua Jackson during the Entertainment Weekly reunion. “I mean, kids are smart.” (Fox had actually bought the concept before the WB, but passed on the project upon reading the script, saying “no one talks like that.”) The teens spoke with a savvy verbiage beyond their years, ping-ponging between references to sex, politics, and pop culture, and using ridiculous euphemisms — like “walk your dog” and “jerkin’ his gherkin” — to stave off the network’s Standards and Practices.

It’s true you’d be hard-pressed to find an equally grandiloquent teen — or adult — in real life (and if you did, they’d be nerve-grating), but there was something commendable about the show’s writers playing to their audience’s intelligence rather than anticipating their ignorance. It’s a consideration rarely afforded to teens. Look at this year alone: Many have been awed by the resolution and eloquence shown by the surviving Parkland students, by 13-year-old activist Marley Dias as she promotes both her #1000BlackGirlBooks campaign and her own book, and by 16-year-old Madyson Arscott, who organized a rally in response to the murder of 15-year-old Tina Fontaine, an Indigenous teen in Canada. Meanwhile, some adults are still surprised at the smart, topical articles in publications like Teen Vogue and Rookie, content that’s gobbled up by teens. Likewise, though the possession or comprehension of a dense vocabulary doesn’t necessarily equate intelligence, the dialogue on Dawson’s Creek wasn’t flying over teens’ heads; instead of tuning it out, teens rose to the level of the show.

It’s also worth considering the vocabulary — if not entirely realistic — as symbolic, representing the weight of emotion being felt. Unlike more “issue-based” teen shows, Dawson’s Creek was less about after-school special–style lessons or warnings and more about firsts. (Williamson maintained the show was about romance — “sweaty palms and weak knees” — not horny teens.) It might be hard to remember those firsts now, but when the rumblings around first kisses, crushes, and heartbreak, as well as formative experiences through experimentation, rejection, and the general loss of innocence are felt, they’re earth-shattering and prone to hyperbole. Dawson’s Creek provided a haven to work out the new, confusing emotions accompanying these moments without belittling them. Whether or not teens watching the show could express themselves as articulately as their Capeside counterparts, they were still able to see a mirror of the complex feelings they were grappling with in their own lives.

Unlike the glamorous lifestyles shown in shows like Beverly Hills, 90210 and later The O.C., both on Fox, the stories of teens on the Creek felt somewhat accessible. And when it came to what made Dawson’s Creek so significant to its teen viewers, it wasn’t just the words, it was who was saying them. On the other end of the spectrum, quieter shows like the short-lived My So-Called Life (which ranked 95 out of 103 primetime shows on air at the time) and even the WB’s sweetly collegiate Felicity (whose initial strong ratings later took a hit due to changes in plot, timeslots, and a hairstyling fiasco) were more grounded and revered by critics, and probably helped teens feel authentically represented; the shows were poignantly accurate in their portrayals of teen isolation and behavior. But Dawson’s Creek, with all its overwrought verbosity, helped teens feel heard and understood by articulating complex and thorny things that felt otherwise indescribable or incomprehensible. Growing up, I relied on the show to help process my feelings because I didn’t (and still usually don’t) have the verbal capacity or confidence to express them myself. When I struggled for the right words, Dawson’s Creek was providing them.

While so many people dismiss Dawson’s Creek as trivial teen fodder, its two-part series finale showed a depth and resolution that even the best of shows — regardless of audience — can fail to reach. After two mostly lackluster seasons in college, the finale, which creator Kevin Williamson came back to pen, was surprisingly satisfying. A fast-forward to five years in the future, it managed to balance messages both hopeful and heartbreaking. Dawson made it to Hollywood and was living out his directorial dreams. Back in Capeside, Jack found a happy relationship and had become the supportive high school teacher he never had, while Pacey, defying the underachiever label so often assigned to him, owned a bustling restaurant. Book editor Joey chose Pacey once and for all (was it that hard?) and somehow did so without downplaying her connection with childhood bestie and soulmate Dawson. And Jen, a single mom to a baby girl, died from a heart condition, which in turn forced her friends to address what was lacking in their lives.

But despite Jen’s plot-serving martyrdom, her passing wasn’t that heavy-handed. After all, Dawson’s Creek was partly about the death of innocence, and that includes facing death in itself. By the show’s end, Jen had arguably evolved the most out of all the main characters, and she was the best equipped to face tragedy head-on. And similarly, Dawson’s Creek left its viewers a little more prepared for what the world had in store for them, the good and the bad.

In the final season, an episode before the two-part finale, Joey delivers a voiceover monologue in which she waxes poetic about the scared little girl she no longer is. She talks about missing that girl, about wanting to comfort her, to tell her to relax, to cherish those she grew up with and their experiences together. She also contemplates the power and imprecision of nostalgia, echoing the thoughts of millions of teens who paddled to Capeside weekly in their minds and who inexplicably still hold those trips dear to their hearts.

“Why are we so quick to forget the bad and romanticize the good?” Joey asks herself and the audience. “Maybe it’s because we need to believe that the time we spent together actually meant something, that we were there for each other in a time in our lives that defined us all, a time in our lives that we will never forget. I can’t swear this is exactly how it happened. But this is how it felt.” ●