Twenty years ago, the biggest film in the world was about the world’s potential end. Armageddon — the action-packed, logic-defying blockbuster in which rugged oil drillers blast into space to destroy an Earth-bound asteroid — earned over $553 million globally (that’s over $850 million today, with inflation), making it 1998’s top film and, as Disney’s most expensive at the time, a worthwhile investment.

Armageddon achieved world domination despite how easy it is to mock. In addition to earning the ire of critics, it received multiple Razzie nominations (Bruce Willis “won” Worst Actor, but An Alan Smithee Film: Burn Hollywood Burn cleaned up that year). In February 2013, Neil deGrasse Tyson tweeted his disappointment over not being able to stream Armageddon and fact-check it (and Netflix wrote him a troll-y response five years later that amassed over 232,000 likes). Then, in April 2013, after director Michael Bay had an interview with the Miami Herald to promote his heist flick Pain & Gain, outlets ran gleefully wild with headlines announcing “Michael Bay apologizes for Armageddon” despite his quote being taken out of context (he regretted how little time they had to finish the film). And in June 2016, a snippet of Ben Affleck’s commentary track in which he roasts the blockbuster — “This is a little bit of a logic stretch, let’s face it” — went viral.

Frankly, all of the ribbing feels earned. Armageddon relies heavily on kinetic chaos and stylized spectacle, as well as the suspension of reality (e.g., fire in space). But Armageddon was never supposed to be scientifically accurate, at least according to its director. “Armageddon is like a total fantasy for a 15-year-old,“ Bay told the New York Times in 2001. “It’s funny — when the critics tried to review Armageddon. I mean, relax, it’s a popcorn movie. It’s not supposed to be taken seriously.” And in an Esquire profile later that year, he assigned its genre as he saw it: “Armageddon, when I look at it now, it’s like a comedy. It’s like a fantasy comedy, all right?”

Bay has been loathed and lambasted throughout his career despite the proven lucrativeness of his films, which so far have earned over $6 billion in box office sales worldwide. The divisive, feather-haired granddaddy of the modern summer blockbuster is a trailblazer who cleared his own path by means of explosives, and his repeatedly ridiculed style has been imitated in bombastic box office bait ever since.

Armageddon validated a fantasy, one that pervades and perhaps helped decide the last US presidential election: that the men of Middle America know better than establishment elites.

While Armageddon is certainly a popcorn movie, there’s no clear consensus on the blockbuster’s genre. Some say it’s action while others see it as sci-fi or fantasy. Some consider it a disaster film while others have deemed it conservative propaganda. The script — worked on by nine writers, five of whom were credited, including a fledgling J.J. Abrams — is full of wisecracks that could justify its place in the comedy category. Plus, Armageddon is a star vehicle for both the established and up-and-comers; Steve Buscemi, explaining his attraction to the project, saw it as an ensemble character film. And for some spectators, Armageddon was a father-daughter story and a romance (the love story, not originally meant to play a central role, was eventually emphasized to help carry the film, perhaps partly inspired by the colossal success of Titanic). And of course, it also serves as a feature-length commercial and an Aerosmith visual album.

But whatever it was, whatever it offered, people watched. The film, despite its clashing tones and many, many faults, has become canonical. (It’s even found a home in the Criterion Collection, between Tokyo Drifter and Henry V.) Armageddon is a ridiculous movie, yet still it endures. Why has it eluded the trash heap of forgotten summer blockbusters to remain, 20 years after its release, a movie so many of us love — or at least, a movie so many of us love to hate?

There are many possible reasons. For Bay’s target audience of adolescents, Armageddon may have been their first time falling in love (or lust) with young stars Ben Affleck or Liv Tyler, or both. And now that those targeted teens have grown up, there’s a nostalgic appeal to the movie’s undeniable corniness. Plus, Armageddon was a feel-good movie about “regular guys” saving the world, which may have comforted early audiences to whom the apocalypse was still pretty much unfathomable. And it validated a fantasy, one that pervades and perhaps helped decide the last US presidential election: that the men of Middle America know better than establishment elites.

Armageddon has so much — maybe too much — going on. A one-size-fits-all movie could easily be a chaotic mess — but it’s hard to deny that it manages to have something for everyone.

When Armageddon premiered in 1998, the world was a different place. More specifically, the US was a different place. The Twin Towers stand proudly in one of the film’s first scenes; the nation was economically stable, with unemployment rates at their lowest in decades; and the global financial crisis was yet to hit.

Michael Bay wasn’t doing too shabby either. After launching his career directing music videos for the likes of Meat Loaf, Lionel Richie, and Tina Turner (and, yes, later Aerosmith), as well as commercials for Nike, Victoria’s Secret, and the “Got Milk?” campaign (including an award-winning ad that taught viewers who shot Alexander Hamilton before Lin-Manuel Miranda would), he blasted box offices with Bad Boys and The Rock, which together made nearly half a billion dollars worldwide. Both films were commercial successes that shook up what action films could be and readied him for Armageddon, his biggest blockbuster yet and one that would cement his cinematic style. Then 33, Bay felt good about the film’s prospects and, according to a DVD review on his official website, cited the rule of threes: “Three movies make people in Hollywood and Armageddon was my third project, so I was very confident.”

While we now live in a time when end-of-the-world fare thrives thanks to its conceivability, the apocalypse felt so implausible in 1998 that Armageddon had to open with Charlton Heston’s ominous voice reminding the audience how an asteroid was enough to take the dinosaurs down. “It happened before. It will happen again,” warns Heston, his rasp ripe with drama. “It’s just a question of when.” The film then fast-forwards to 65 million years later as a meteor shower hits Manhattan.

When we first see Harry Stamper (Bruce Willis), he’s on his oil rig in the South China Sea, winding up a golf swing. He shoots, he smirks, he watches as the dimpled ball hits its target: Greenpeace protesters on a nearby ship chanting “Stop the drilling!” ZZ Top’s “La Grange” — a song whose guitar riff has become synonymous with arrogance, attitude, and general badassery — plays in the background.

We soon get to know Harry’s crew. There’s A.J. (Ben Affleck, in his first heartthrob role), the stubborn smartass who’s been getting busy with the boss’s daughter, Grace (Liv Tyler, also strikingly attractive), on the sly. There’s Rockhound (Steve Buscemi), a genius with a penchant for skirt-chasing, and “Chick” (Will Patton), a regretfully absentee father who’s Harry’s right-hand man. We’re introduced to what were two less-familiar faces at the time: Owen Wilson as Oscar, a cowboy with surfer appeal and some of the film’s best lines, and the late Michael Clarke Duncan — discovered by Bay at the gym — as “Bear,” the brawny but subversively sensitive one (and one of the film’s only actors of color). Throw in a chubby mama’s boy (Ken Campbell) and an expendable, ambiguously attractive white man (Clark Brolly), and you’ve got ‘em: the latter-day Dirty (not-quite-a) Dozen, who hope to never pay taxes again. These are the misfits from Middle America summoned by the elite — that is, flailing NASA nerds — to destroy an asteroid “the size of Texas” hurtling toward Earth. These roughnecks are the world’s best hope.

Armageddon was modern-day myth-making, but it went beyond a simple underdog story or hero’s journey.

Armageddon was modern-day myth-making, but it went beyond a simple underdog story or hero’s journey. To a discerning eye, it was pure, proud “rah-rah America” propaganda. It reveled in a “call to duty” brand of nationalism, complete with NASA honcho Dan Truman (Billy Bob Thornton) acting, in ways, as a less-stern, better-dressed Uncle Sam. Case in point: The two shuttles launched in the film are named Freedom and Independence. And when our heroes’ mission, toward the film’s end, is announced to be — spoiler alert — successful, we see, in addition to some global scenes of celebration, images rooted in small-town American nostalgia but presented as present day: (white) American kids racing down roads in soapbox cars (is it 1998 or 1958?) and running with toy spaceships in front of a giant mural of John F. Kennedy, the words “peace” and “life” around his smiling face. Astronaut Willie Sharp (William Fichtner) then radios down to mission control: “Kennedy, we see you. And you never looked so good.”

The blue-collar, red-blooded American motley crew lends itself to the comedy of Armageddon — working-class dudes in space are clearly fish out of water — but these men are also crucial to Armageddon’s success as an earlier form of the contemporary disaster film. That boom was ignited by 1996’s Independence Day and kept burning through films like Dante’s Peak, Volcano, Titanic, and even Deep Impact, a film that opened two months before Armageddon with a similar premise, but a more grounded storyline. American moviegoers like seeing everyday Joes — themselves — as potential heroes capable of saving the world, not people with special training, gifts, or skills. Bruce Willis’s and Ben Affleck’s modest, prideful heroism lends audiences the assurance that the apocalypse is not just avoidable, but that the right people will do the right thing and save the day. Just trust.

Of course, ruggedly handsome white guys don’t accurately (or at least entirely) represent the face of “regular, everyday America.” And it’s this sort of blind mentality that might contribute to the film’s jingoism (e.g., non-Americans shown sparingly, in cliché-laden group contexts) and its cross-cultural ignorance (e.g., at one point, Hindus and presumably Sikhs — judging by the turbans, but who knows in Bay’s version of the world — are shown praying at the Taj Mahal, an Islamic mausoleum). Nevertheless, Armageddon was a global sensation. It’s not entirely surprising; US culture is everywhere and participating in its consumption is par for the course for many non-US countries. But disaster films have a leg up on other genres. Their special effects and visual bombast are enough to mesmerize audiences despite lackluster translation and, in the case of Armageddon, supernationalistic elements.

According to Ben Affleck’s viral DVD commentary on Armageddon, Michael Bay grew tired of his leading actor’s questions about the film’s absurd plot.

“You know, Ben, just shut up, okay? You know, this is a real plan. Alright?”

Affleck kept prodding. “You mean it’s a real plan at NASA to train oil drillers?”

“Just shut your mouth!”

Bay telling Affleck what to do with his mouth wasn’t new; the actor was reportedly asked to get $20,000 worth of dental work to look more heroic for the film. (Sure, the everyman can save the world — but only if he has perfectly even pearly whites and not, as Bay called them, “baby teeth.”) Bay also reportedly hired a trainer for Affleck to make sure his abs were as chiseled as his jaw. “I remember Ben coming to me one day and saying ‘You’re not going to believe what happened to me,’” Liv Tyler told People magazine in 2002. “Basically Michael Bay had just made him stand there and have running water poured over his bare torso. He didn’t even know what scene it was for.”

These ridiculous details give us insight into Michael Bay’s style of filmmaking: He seems to intentionally favor looks and optics over logic. But it’s also this prioritization that helped make Armageddon a standout action flick — absurd plot and Affleck’s protests be damned.

Bay and his directorial tendencies — sweeping camerawork, shots from high or low angles, overblown explosions, state-of-the-art special effects, cheesy one-liners, rapid cuts, creating universes that seemingly exist only in the orange haze of magic hour— have become an easy target. (When Pearl Harbor, in which Affleck also starred, came out in May of 2001, Bay admitted in a Rolling Stone profile that the movie would be more readily championed if it weren’t directed by him.) He’s known to be heavy on spectacle, light on substance. And Bay is not just self-aware when it comes to his obsession with “awesome” visuals (see his Verizon commercial), but unapologetic. “I don’t see anything wrong with spending a lot of money to make big action movies to entertain people,” he said in an Entertainment Weekly profile from 1998 titled “Is Michael Bay the Devil?” “Yet somehow, I come under special scrutiny. I mean, why don’t people get upset if Dow spends $300 million to invent some new chemical? Audiences like popcorn movies. What’s wrong with that?”

Armageddon becomes a descent into Bayhem — a filmmaking style that’s come to define the summer blockbuster — and a crash course on his methodical madness. The thing is, though Bay goes to great lengths to make things in the movie look realistic, his is a version of ultra-slick, burnished hyperreality. The production had unprecedented access to NASA facilities, but even they weren’t always enough for the director. Bay said their mission control station was “the most unsexy thing you’ve ever seen” on the Criterion DVD commentary, and he went to great lengths to make the agency look more sleek and modern.

The year before Armageddon was released, James Cameron’s Titanic had been ruling box offices. Both Cameron and Bay have reputations as difficult, demanding directors with obsessively meticulous approaches to their epic films, though Cameron seems to have earned far more respect among cinemagoers and critics. Still, they share a mutual appreciation of each other’s work; Bay, who first met Cameron when visiting the set of Titanic, names him as an idol while Cameron says he’s studied Bay’s films and that “he loves what I call ‘the big train set,’ huge physical production, just as I do. It is the most challenging type of filmmaking, and he does it gorgeously.”

Bay telling Affleck what to do with his mouth wasn’t new; the actor was reportedly asked to get $20,000 worth of dental work to look more heroic for the film.

Though Bay was pelted with bad reviews and general hate following Armageddon, more and more critics, filmmakers, and theorists are now ceding to the fact that, in his clear vision and singular style, he’s actually something of an auteur. A 2016 Vox article claims he has “an almost art-house sensibility; it’s just that Bay is applying it to explosions and CGI robots.” Steven Spielberg, in a 2011 Variety piece, argues something similar: “He is so adroit at composition, blocking, camera movement, color and tone, that combined with battling Transformers in multiplanes of crazy action, you can either look at his imagery as assaultive, transformative, or deliriously entertaining.” And while, with Armageddon, Bay’s use of quick cuts was especially criticized — Roger Ebert called it the “first 150-minute trailer” — the director was, in some ways, ahead of the curve. At the time, the frenetic editing of seconds-long clips spliced together might have been overwhelming to the senses, but it’s not nearly as disorienting now. Audiences have acclimated, for better or worse, to a faster pace, especially thanks to Insta stories, Snapchat, Vines (RIP), and even digital content creators like Super Deluxe. Some critics have suggested that his quick cuts are used to hide sloppy filmmaking, but Bay seems to employ them with intention and, as he says, to add a surge of energy.

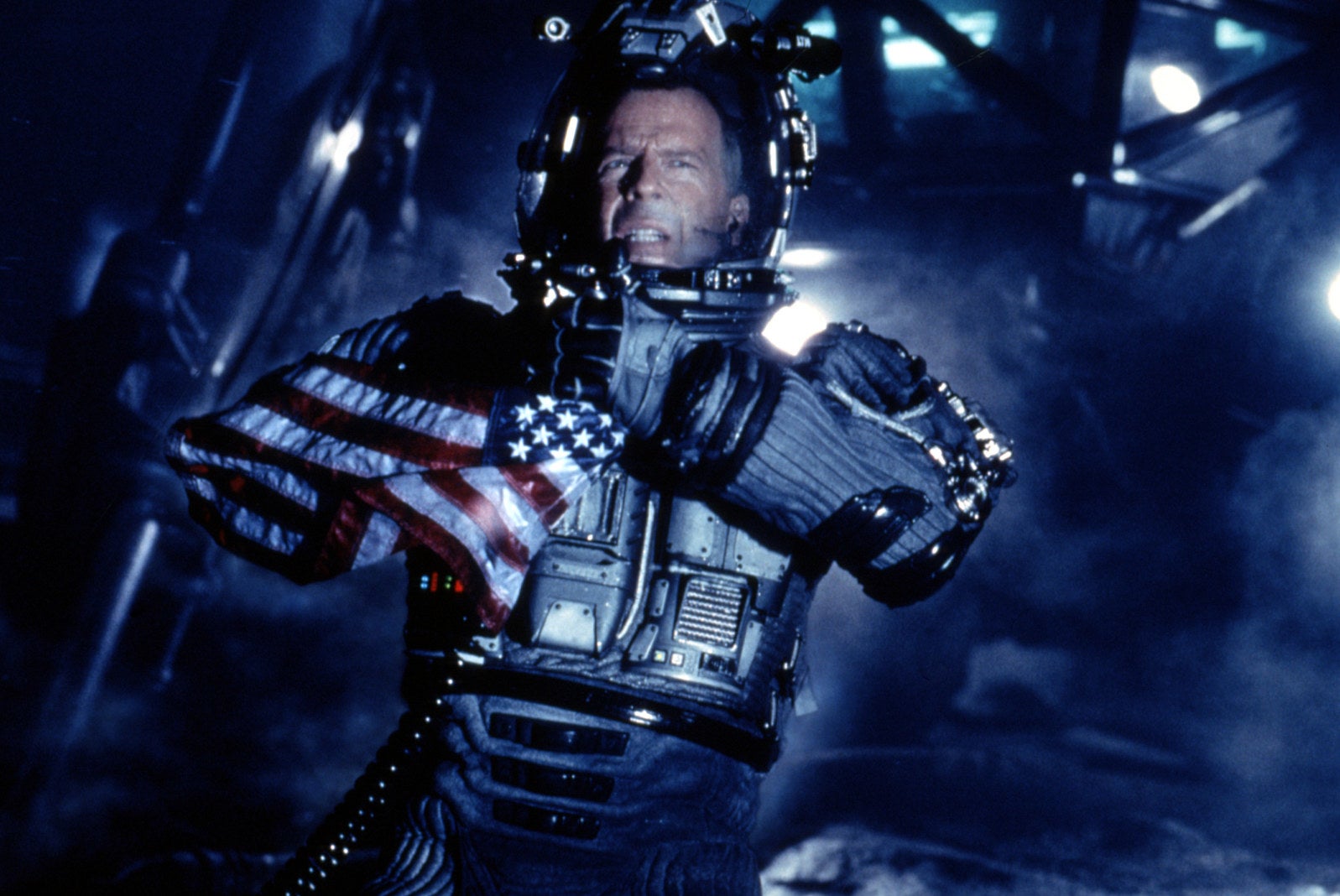

Keep in mind, however, that although Bay is obsessed with visuals and draws from a well of intuitive (and somewhat perplexing) creativity, he’s not actually trying to make art — just stuff that looks cool and provides an overwhelming, fun cinematic experience. At one point in the DVD commentary, Bay discusses his meltdown over the film’s space suits, saying it took about $1.5 million to get them right. “I went to see [the space suit] for the first time and I realized it looked like an Adidas jogging suit on a rack. That’s where I almost killed myself,” Bay says. “Because if you don’t have cool space suits, your entire movie is just screwed, bottom line.”

He goes on, “We had a major problem with our space suit because our designer was French and she had done things with Luc Besson, but they do things very differently in France. They’re very more the ‘artistes’ — this is not big American moviemaking where if you don’t have a space suit that works for a big fucking movie star you are FUCKED. Alright, I’m sorry for the language but this is what goes through your mind because your entire movie hinges on these suits.” An auteur of action perhaps, but Bay had no interest in being an artiste.

For all of the intense specificity surrounding the film’s action and macho elements, and with the exception of a rousing John Denver sing-along, the most memorable scenes of Armageddon are the quieter ones. The day before the mission launch, Harry demands his men get the night off. Truman protests, but Harry has the last word. “I’m not asking you, I’m telling you,” he says, an out-of-focus American flag as his backdrop. “Make this happen.” And so, while most of his colleagues head to a strip club, A.J. spends his potential last night on Earth with his fiancé.

In true Bay style, the moment is filmed like a high-budget commercial. But for what? Possibly the BMW two-seater they drive down a dirt road to their destination: a remote, old-timey gas station. Or for the string lights adorning the tree they decide to lie underneath, swathed by the amber glow of a sunset. Or it could be for Barnum’s Animal Crackers, which A.J. provides a meditation on before using them for foreplay, traipsing the biscuits across Grace’s bare torso.

In reality, the commercial-within-a-movie was indeed for the BMW, one of many product placements throughout the film. Bay could probably use the cash; in the past, he’d had to invest his own money when studios didn’t want to shell out for certain action sequences.

Women are scarce in Armageddon — I counted fewer than 10 with at least a single line, one being “I want to go shopping!”

But the scene is still somehow sweet in its simple intimacy. When Grace asks whether it’s possible that another couple might be doing exactly what they’re doing elsewhere in the world, A.J. replies, “I hope so. Otherwise what the hell are we trying to save?” Cue the impassioned kiss, cue the swelling music: Steven Tyler screeches tunefully in the background along to a strings-and-piano accompaniment, turning power ballad “I Don’t Want to Miss a Thing” into an aubade.

Women are scarce in Armageddon — I counted fewer than 10 with at least a single line, one being “I want to go shopping!” — and Grace, the only significant female character, is more of a motivating factor than a full-fledged character on her own — someone to fight for and come home to. Though she spends limited screentime interacting with the men in her life, namely A.J. and Harry (the rest of her scenes mostly involve looking woeful or crying in NASA mission control), it’s those cheesy but sweet moments with Grace that anchor an otherwise off-the-rails film.

Armageddon’s most dramatic moment comes at its end when A.J., by luck of the draw, has to stay behind on the asteroid to detonate the nuke manually. In a last-minute switcheroo, Harry cuts off A.J.’s oxygen supply and tosses him back toward the air-locked cabin, taking A.J.’s place as the sacrificial lamb and saving his daughter’s future husband. He tells A.J. he thinks of him like a son, gives the couple his blessing to wed, and shares a tender goodbye with Grace via TV monitor, a single tear running down the scruff of his cheek, before he checks out. And in doing so, Armageddon became a story of a father’s love and his self-sacrifice for the sake of his daughter, her fiancé, and, yes, the world.

Dads and father-child dynamics are scattered throughout Armageddon — a fact that feels more significant when considering that Michael Bay, who was adopted, searched for his biological father to no avail. Harry’s crew helped raise Grace as she grew up (“We all feel like a bunch of daddies here,” says Bear). When the mission is complete, Chick is reunited with his estranged young son, and the film ends with Grace and A.J. kissing on the tarmac. The credits roll to footage of their wedding, at which they display a photo of Harry and the other three astronauts lost along the way. And yes, that song — the one sung by Liv Tyler’s real-life dad — plays again.

While it may not be immediately obvious, Armageddon is really a movie about love. Love of America, clearly, but also love that’s romantic, parental, and platonic. And if that’s too schmaltzy for you, it can be a love for danger, for sensory overload, or for blowing things up. It has it all.

Still, it’s worth wondering if Armageddon would be such a smash hit at the box office in 2018. We seem to prefer our heroes to wear costumes these days, and action movies often do best when part of an established franchise. And maybe a disaster movie like Armageddon no longer has the reassuring and escapist charm it once offered. Instead, global cataclysm feels all too possible as we watch Antarctica melt and petty, impulsive leaders govern countries with nuclear weapons in their arsenal. At this rate, the end of the world will more likely be caused by humans, not prevented by them.

There’s a scene in Armageddon where Harry’s ragtag workers take a Rorschach test to see if they’re fit for space travel. (A.J. sees each image as Harry putting him down while Rockhound sees women with varying breast sizes.) And in retrospect, maybe Armageddon is the blockbuster equivalent of a Rorschach inkblot: It’s whatever we want it to be. The ultimate everyman flick is, in a way, an everymovie. And that’s why it never gets old, why we keep flipping to it whenever it’s on TV — even if we no longer live in a world where the likes of Bruce Willis can save us. ●