A man convicted of assault is asking for a retrial after discovering Baltimore Police used a secretive, cell-phone tracking device known as a Stingray.

The challenge is the first of more than 2,000 criminal cases under review in Baltimore that could be retried or overturned after defense attorneys there discovered detectives used the surveillance technology but never disclosed it in court.

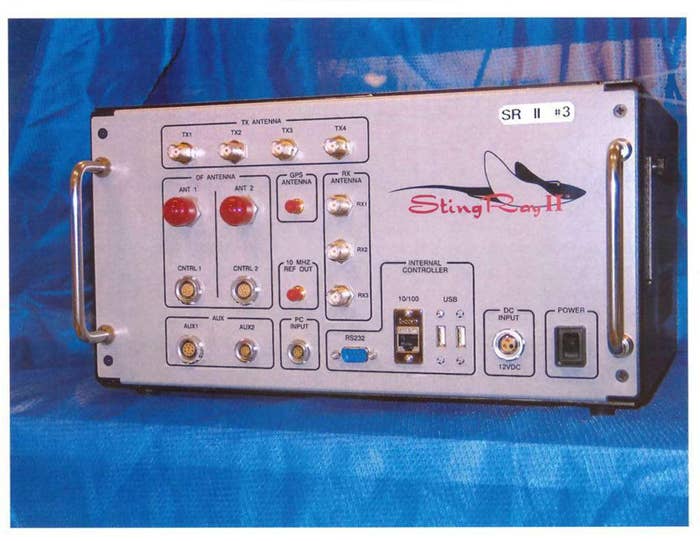

According to the motion filed Friday by attorney Josh Insley, the Baltimore Police and the State's Attorney's Office lied about using cell-site simulators known as "Stingray" — devices that simulate cell phone towers and trick nearby phones into disclosing their exact locations, then collect that data.

Insley alleges detectives and prosecutors lied about using a Stingray because of a non-disclosure agreement they signed with the FBI, which prohibited them from disclosing details of the technology to the public or in criminal court.

Insley told BuzzFeed News he suspected the device was used against his client, Shemar Taylor, when the statement of probable cause cited the use of a "sophisticated electronic device."

But when detectives with Baltimore Police were pressed about the equipment, they offered conflicting testimony in court. And when prosecutors were required to release details about the equipment, they then told defense attorneys that "the device" had not been used at all during the investigation.

"When they wouldn't give them up, and the context in which it was used, we had a pretty good idea" cell-site simulators were used, Insley said.

Taylor later agreed to a deal with prosecutors and pleaded guilty.

But a report by USA Today found police in Baltimore were using the device to investigate ordinary crimes, including the case Taylor was convicted of, Insley said.

Since then, Baltimore's Office of the Public Defender has begun a review of more than 2,000 cases where Stingrays are believed to have been used by police, who then withheld details during trials.

Insley said he is working closely with the Public Defender's office and expects more cases to be challenged in court.

Though first used by the military and federal law enforcement agencies, the devices have since been purchased and used by local police departments.

Before they are cleared to purchase them, however, the FBI requires the agencies to sign non-disclosure agreement that prohibits them from talking about the devices with the public or in court proceedings.

If details are requested in court — for example in criminal trials, where prosecutors are required to turn over all evidence to defense attorneys — the FBI requires police to contact the FBI to "intervene to protect the equipment/technology and information from disclosure and potential compromise."

The technology has come under fire by civil rights and privacy advocates who allege the devices are invasive, and that they indiscriminately collect the information of all cell phones within range.

Law enforcement agencies have also fought for years to keep information about how Stingrays work, or what they are capable of, secret.

This week, the Justice Department changed its policy of how they are used, including requiring a search warrant to be filed.

The policy, however, does not apply to local police.