It has helped crack violent crimes that seemed unsolvable and led police to identify dozens of suspected killers and rapists.

On Wednesday, it was used to exonerate a man in the 1997 murder and rape of 18-year-old Angie Dodge, making him the first wrongfully convicted person cleared of a crime through the use of investigative genealogy. Now experts in this emerging field say the new forensic science of genetic genealogy could be used to exonerate others who may also have been wrongly convicted.

"It's a new life, a new beginning," Christopher Tapp said Wednesday outside an Idaho Falls courthouse after being exonerated of the murder.

Tapp spent 20 years behind bars after he told investigators he had taken part in the grisly attack. But his confession, experts said, was not just coerced but "a virtual recipe for how to take a false confession."

The Idaho Innocence Project took up Tapp's case in 2007 and, after exhausting other options, helped push law enforcement to test DNA found at the crime scene using genetic genealogy in hopes of finding Dodge's real killer.

"The light has to shine in both directions," Greg Hampikian, executive director of the Idaho Innocence Project, told BuzzFeed News. "It has to shine into the future to find criminals, and it has to shine into the past where there has been a miscarriage of justice."

Idaho Falls Police then tapped Parabon NanoLabs, a DNA analysis company and its lead genealogist, CeCe Moore, to employ genetic genealogy to track down the real killer.

Tapp was released and cleared of the rape charge in 2017 after the Innocence Project won a review of the evidence in the case, showing that none of the DNA from the crime scene matched him.

Still, the murder charge remained.

Then, in May, using a 23-year-old degraded DNA sample from the original crime scene and investigative genealogy, police announced they had found the man behind the brutal killing.

Brian Leigh Dripps, who once lived on the same street as Dodge, had confessed to the killing, and his DNA matched the original profile of the suspected killer.

On Wednesday, Tapp was officially exonerated in court.

"Chris is an innocent man; he's been innocent all along," Tapp's attorney John Thomas said at a press conference.

Investigative genealogy burst into the national headlines in April 2018 when California police announced the arrest of Joseph James DeAngelo, a former police officer and the suspected “Golden State Killer.”

By uploading DNA collected from a crime scene to public genealogy databases, investigators try to locate distant relatives of suspects. Then, assembling complicated and time-consuming genealogical trees, they work to trace the lineage to a possible suspect.

The investigative method had once been used almost exclusively by genealogists helping people trace their family history or find birth parents or long-lost relatives. Now police departments across the nation are reaching out to private companies and the FBI to make use of the new technique.

Since the arrest of the suspected Golden State Killer, more than 70 suspects and victims of rape and homicide have been identified by police across the country using genetic genealogy, including decades-old cold cases that had previously led detectives to dead ends.

Experts say that with the method having helped Tapp clear his name, more people wrongly convicted of crimes will likely be exonerated using investigative genealogy.

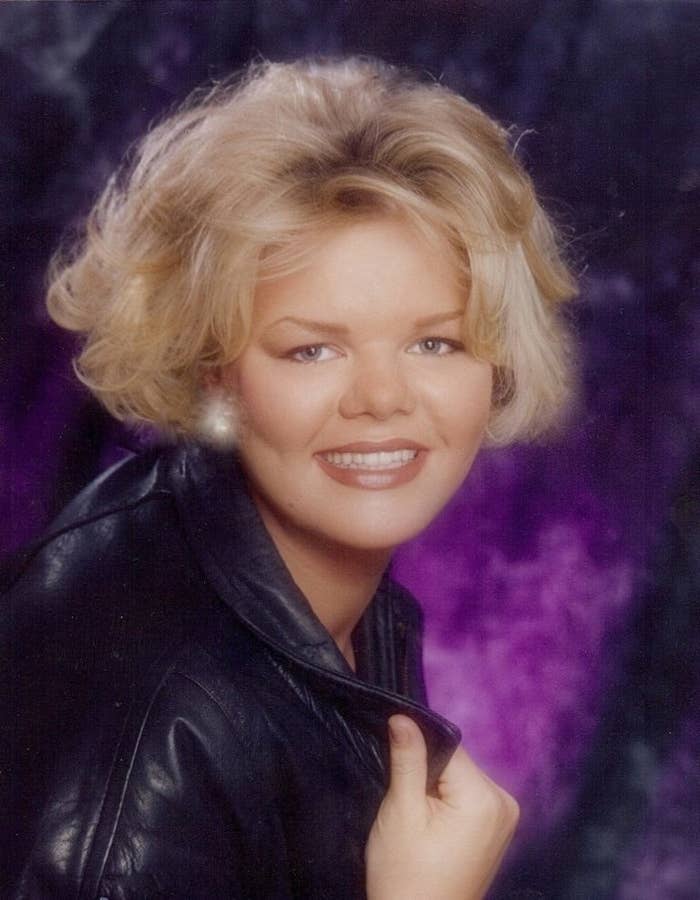

"I certainly expect to help many more people," Moore, the genealogist who worked to identify Dripps as Dodge's real killer, told BuzzFeed News.

Parabon has become a leading player in investigative genealogy and is responsible for more than 50 of the publicly known cases where a suspect or victim has been identified. It has, and continues, to work with police departments across the country.

Although the focus over the past year has been on identifying crime suspects, Moore said she sees her work as also helping to clear the names of dozens, sometimes hundreds, of suspects that police compile when they're working to crack cold cases. While their names are often not public, the suspects are often contacted repeatedly by police looking for a break in the case.

"The next step is getting someone out of jail," she told BuzzFeed News.

Helping to identify suspected killers has been an important part of her work, she said, but helping to clear Tapp of Dodge's murder has been the most gratifying work she's done so far.

"This was different," she said. "This was pure joy."

The Idaho Innocence Project first took up the case after Tapp sent a handwritten letter to the organization claiming his innocence.

Semen and a pubic hair left at the scene of the crime were found not to match Tapp's genetic profile despite multiple searches. A teddy bear that Tapp told investigators he had held during the crime was found to have no DNA evidence that matched him, either.

The Idaho Innocence Project's Hampikian told BuzzFeed News the group tried repeatedly to find the origin of that unidentified genetic code.

There were no links in criminal databases to the crime scene DNA, and the organization had also tried, unsuccessfully, to convince Idaho law enforcement to perform a familial search, in which relatives of the suspect would be sought in criminal databases.

"For 20 years, Chris Tapp and the DNA evidence was saying, 'You have the wrong guy,'" Hampikian said.

In 2017, Tapp cut a deal with prosecutors: With none of the DNA evidence linking him to the crime, he was cleared of the rape charge and released from prison, but he would continue to have the murder conviction on his record.

As part of the deal, however, the Idaho Innocence Project would keep the original DNA crime scene sample, which the organization continued to use to try to clear Tapp.

"We said, 'Let's pretend this DNA is an orphan and is trying to find its daddy,'" Hampikian said.

Then the Idaho Falls Police Department, willing to take a shot with this new investigative technique, brought in Parabon and Moore in.

Moore said the sample she worked with had been severely degraded, and when she ran it through the public database GEDmatch, she found only distant familial connections, making her pessimistic about finding a break in the case. It was when she got a call from Carol Dodge, Angie Dodge's mother, asking her to test the sample that Moore said she decided to trace the genealogy of the DNA.

Carol Dodge had grown convinced of Tapp's innocence and had begun to reach out to media, the Idaho Innocence Project, and attorneys to help prove he was not the killer. Dodge had heard about investigative genealogy and decided to call Moore directly to ask her to take up the case.

In April, Moore said, she finally caught a break, finding a distant third cousin to the suspected killer. The genealogy pointed her to Brian Leigh Dripps.

The match didn't just bring closure to the case but showed that genealogists could use degraded DNA samples in investigative genealogy, Moore said. It also highlighted the possibility that investigators could use the technique to find the origin of unidentified DNA evidence, especially in cases where the conviction of suspects is being questioned.

Hampikian said the Idaho Innocence Project is currently working on cases where the person convicted does not match DNA evidence from the scene — prime cases for investigative genealogy. They're reaching out to companies, like Parabon NanoLabs, to look at their options.

"I want that DNA identified," he said.

For the moment, however, genealogists are limited in their pursuit of matches in public databases.

After GEDmatch made an exception to its terms of service to allow law enforcement to search for a suspect in a violent assault case (the conditions were previously limited to sexual assault and murder), privacy concerns from users prompted the company to make changes to its use.

Users must now opt in to have their DNA profiles available to law enforcement.

Moore said this change has severely limited the possibility of genetic genealogy for the moment, but Parabon is still working on about 200 cases that had already been put through the database.

Hampikian said he's aware of the privacy issues surrounding the practice, but he's also concerned that if the tool is available to law enforcement, it must also be available to defense attorneys and groups that are trying to help those who may have been wrongfully convicted.

"The question is, who can use these tools? Who owns the human genome?" he said. "The fact is, this is solid science, and it leads to truth."