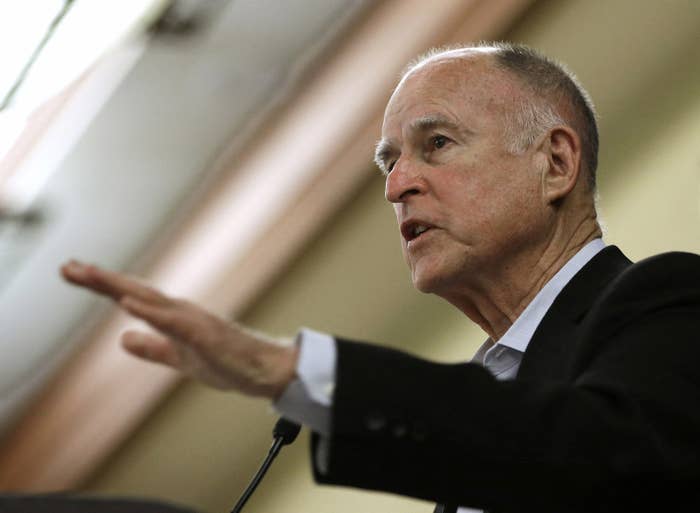

Authorities in California will need a warrant before accessing private electronic data, such as emails, text messages, or the GPS location emitted by cell phones, after Gov. Jerry Brown on Thursday signed a new privacy bill into law.

The new requirement means investigators will also have to obtain a search warrant before deploying cell-site simulators known as Stingrays — a secretive tool used by law enforcement that tricks nearby cell phones into revealing their exact location.

The California Electronic Communications Privacy Act is one of several recently adopted measures that curbs law enforcement's access to electronic data.

Civil rights groups on Thursday called the law a landmark victory for the future of digital privacy.

"Governor Brown just signed a law that says 'no' to warrantless government snooping in our digital information," Nicole Ozer, technology and civil liberties policy director at the American Civil Liberties Union of California, said in a statement. "We hope this is a model for the rest of the nation in protecting our digital privacy rights.

State Sen. Mark Leno, who co-wrote the bill, had introduced two other similar bills that were vetoed by Brown.

SB 178 had been widely opposed by the state's sheriffs, police chiefs, and prosecutors. The respective associations had aired concerns the bill would affect investigations into child pornography and online predators.

"It is an ill-thought-out piece of legislation that will have dire consequences for the men and women on the front lines of the fight to stop child exploitation and human trafficking," the National Association to Protect Children said in a statement.

The bill that was ultimately signed by Brown provides exemptions for law enforcement, such as when someone is in immediate danger.

"For too long, California's digital privacy laws have been stuck in the Dark Ages, leaving our personal emails, photos, and smartphones increasingly vulnerable to warrantless searches," Leno said in a statement. "That ends today."

The Electronic Frontier Foundation, which supported the California bill, also called the privacy law a win for the public, stating "law enforcement can't poke around in their digital records without first obtaining a warrant."

Before the bill was signed, police agencies were allowed to tap service providers to reveal information about their users, as well as metadata from servers or cell phone towers.

The law would also affect the way some law enforcement agencies use cell site simulators, commonly known as Stingrays.

Though law enforcement agencies have released little about how the technology works, the devices are known to collect data from nearby cell phones and pinpoint their exact location.

In California, law some law enforcement agencies notify courts before deploying them, but the new law would require a search warrant, and therefore that authorities establish "probable cause" in court.

Agencies such as the Sacramento County Sheriff's Department, which in September said that it would get "judicial authorization" for the stingrays despite not needing a warrant, will now have to get one.

In May, Washington state adopted a similar law requiring a warrant for the secretive technology, including describing how it works.

Utah, Minnesota, and Virginia have also adopted similar laws in the past year. And in September, the Justice Department tightened its policy on using the devices by requiring a search warrant before they are deployed.